December 28, 2016

Creative Placemaking: How to embed

Arts-led processes within cultural

regeneration?

Written by Anita McKeown

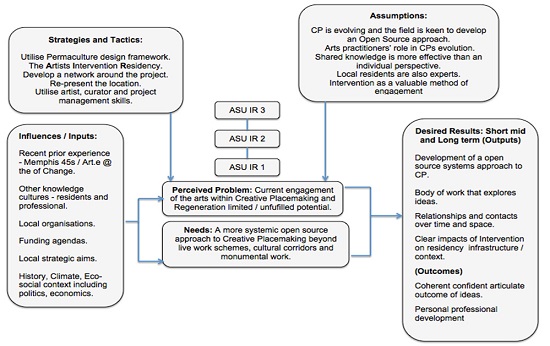

Creative Placemaking (CP), a strategic policy platform that was established in the USA, (Landesman, 2009) is a sub-field of ‘Placemaking’ and can be considered as the latest iteration of the evolving effort to embed Arts-led processes within cultural regeneration. ‘Cultivating permaCultural resilience (pCr) – towards a Creative Placemaking critical praxis’ (McKeown, 2015) integrated the ethics and design principles of Permaculture, into Situated Art Practices to develop a critical praxis for Creative Placemaking.

Informed by the Situationists’ dérive, Art Services Unincorporated[1] (ASU) re-imagined CP as a situated process of creative co-production for self-organisation. The initiation of a process of self-organised CP is achieved through the creation of opportunities to reveal and actualise local potential and resources and encouraging emergent adaptive behaviour and resilient practices from the inside out. As an emergent critical praxis (a theoretical framework, practical toolkit and nascent evaluative matrix) - permaCultural resilience, fosters the ability of a location to adapt to changing conditions initiated by a systemic arts-led process.

Proposed as an operating system for CP, the pCr approach grounds an eco-social commitment into CP to foster opportunities to re-imagine existing place-narratives that include diverse understandings of place. Trialled in London, Ireland and the U.S.A. by an itinerant artist-in-residence, this summary outlines the emergence of CP and the aims of ASU’s research; to enshrine the dynamic, emergent and ethical qualities of permaculture design within a Situated Arts Practice to contributes to the on-going evolution of CP - a deeply politicised practice and philosophy.

What is Creative Placemaking?

Creative Placemaking (Landesman, 2009) is a US a strategic policy platform with a distinct heritage that has been quickly adopted and exported internationally. Currently there is enthusiastic uptake by funders, governments and arts councils in India, Korea, UK, Europe and Ireland. As CP gains traction (Bergstom, 2012; Gadwa, 2012, 2013; Coletta, 2010) with governments and spatial planners, historical concerns linked to development, formal masterplans and zoning arise. Further, there is a corresponding increase in the potential of dominant narratives - established through socio-political or cultural boundaries - to shape and define the performance of a location’s identity (Lanham, 2007). Polarised approaches to regeneration i.e. management-led (top down) and grassroots, collaborative (bottom-up) constrains the potential of an agile approach utilising Arts and Cultural leadership that recognises multiple narratives and expertise.

In 2010, the National Endowment of the Arts newly appointed chair, Rocco Landesman commissioned Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa-Nicodemus to expand upon Landesman’s first observations on how American cities were being revitalised by the Arts. Their paper identified three shared characteristics from the selected case studies[2]:

1. Strategic action by cross-sector partners

2. A place-based orientation

3. A core of arts and cultural activities

and helped to define Creative Placemaking thusly:

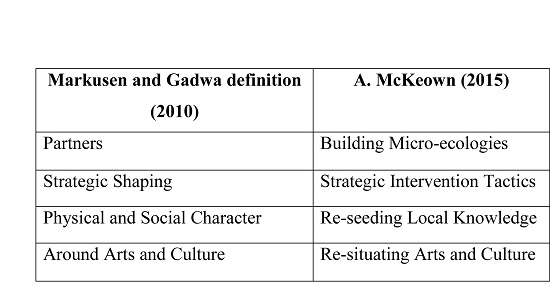

In Creative Placemaking partners from public, private, non-profit, and community sectors strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighbourhood, town, tribe, city, or region around arts and cultural activities. (Markusen and Gadwa, 2010)

Acknowledgement of the ability of ‘artwork interwoven into the public realm [to serve] as a social catalyst or as a way to reveal complex ideas and issues’ (4 Culture, 2007:10) has grown, yet how might this manifest in light of current environmental and economic climates? What are the limitations of current CP practices for an integrated socio-ecological approach? How might an integrated systems framework, underpinning a process of CP address some of these limitations?

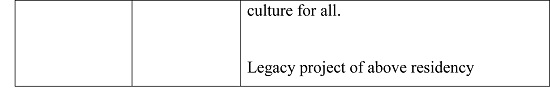

The research demonstrated the impact of enshrining the dynamic, emergent and ethical qualities of permaculture design within a Situated Arts Practice. As an explicit act of CP, this contributes to the on-going evolution of CP both as a practice and as a philosophy. Utilising an agile method, the research explored a form of arts-led development that operates from the inside-out rather than top-down or bottom-up to encourage cultural dynamism: an innovative, local, scalable open-source systems approach to CP. A tactically Situated Arts Practice, utilising the systems design framework of Permaculture, in combination with an open-source ethos formed the key method - an itinerant artist-in-residence that traversed the boundaries of media, contexts, and disciplines. Through the development, as part of this research, of a systemic methodological framework and practice-based method of critical engagement, CP is re-imagined within the context of a situated networked co-production.

Synthesising ideas from four fields, the development of the sustaining knowledge ecology that supports the proposed CP critical praxis focussed towards resilient places achieved through supporting vital cultural ecologies of place.

A systemic approach to CP

The likely impact of future global challenges necessitates the development of sustainable resilient communities. The research presented an opportunity to explore and understand problems from a localised systemic perspective, beyond commodification of social and ecological capital adapted for eco-consumerism and produced by a globally scaled capitalist system. Understanding a system and finding the sources of its problems or issues as well as its existing resources and resilient capacity are processes embedded within the research’s design. Recognising that the solution is not separate from the problem (Mollison and Holmgren, 1978; Krishnamurti, 1973) demands that the problem is correctly identified and may require unconventional solutions (Meadows, 1972, 2008).

In general, resilience thinking recognises the interdependence of humans, the physical environment and systems, both built and natural. Within the research, the term ‘resilience’ is understood as a quality within a socio-cultural ecosystem or ecology, which - through an intimate understanding of its assets and resources - can be empowered to draw on those resources, thus enhancing and sustaining an ability to manage change. This understanding informs the research’s exploration of the initiation of socio-cultural micro-ecologies through temporary ‘commons’ as occasions to explore and expand the relationships, resources and opportunities within a geo-location; an emergent process of permaCultural resilience.

A Tactical Approach to CP

Since Lefebvre’s prophecy of worldwide urbanisation (2003, [1970]), the concept of planetary urbanisation has become a persistent presence within Urban Studies (Brenner and Schmidt, 2014; Merrifield, 2009; Soja and Kanai in Burdett and Sudjic 2005). That is, the processes and networks of urbanisation have penetrated all aspects of contemporary life, including areas of wilderness, oceans and the universe, whether as communication waves, acid rain or space debris. As the ‘-ness’ of place is increasingly commodified to entice or retain new residents (Loflin, 2012; Florida, 2002), the dominant narrative of planetary capitalist urbanisation further commodified through sustainably ‘lite’ convivialities, e.g., the coffee shop (Zukin, 1988) is always present.

The research endeavoured to contribute to an expanded understanding of CP facilitating a re-location for citizens from ‘planned’ to ‘planners’ (Dakin, 2003a) in light of the context of Planetary Urbanisation. CP is re-imagined as a local-scale, open-source process to re-draft the ‘script of our own lives’ (Debord, 1988) within the places in which those lives are enacted.

An Open Source Approach to CP

Various scholars have issued critiques of CP, calling for more accessible equitable and participatory practices (Bedoya, 2013a; Brenner, 2013b; Mehta, 2012). Yet deeper understandings informed by eco-social and cultural debates around place construction are not yet fully integrated into the academic discourse of Creative Placemaking academic discourse. Within the research’s projects, citizens’ tacit and situated knowledge cultures, their histories and cultural experiences are brought to bear on a process of CP that strives to initiate pCr.

Art Services Unincorporated’s (ASU) approach recognises local residents as experts already presenting resilient behaviour. Their eco-socio cultural knowledge and resilient capacity becomes central to understanding ‘localised problems’. Potential solutions identified and grown from within the problem in this way modify Creative Placemaking away from a focus on the built environment and towards a processual resilient practice. If CP is to avoid negative manifestations of place marketing and place branding strategies or of gentrification or inequitable practices, then it can be seen that a critical praxis that leverages the Arts and Culture to support equitable citizen-led practices of CP is required.

A Situated Art Practice Approach to CP

Historically, inclusion of the Arts within regeneration practices has been championed to attract investment for post-industrial cities, particularly in the face of interspatial competition (Florida, 2002; Swyngedouw, 1992; Harvey, 1989). Further, the Arts have been argued for as a positive influence on urban development and built environment projects through their contributions in terms of social impact and the empowerment of communities (Vazquez, 2012; Matarasso, 1997; Landry et al., 1996). Markusen and Gadwa have repeatedly emphasised the CP definition is incomplete and that the evolution of CP is necessary and the research sought to make a deliberate and specific intervention into that argument through praxis.

Deliberately integrating the heritage of non-object-based arts practices and discourses underpinning the ‘New Situationists’ (Doherty, 2004b) into CP the research integrated important debates pertaining to social engagement in and through the Arts into the socio-political construction of place. An arts-led processual making of place, driven from the inside-out and tactically engaging with socio-cultural and environmental issues, has not been explored. The pCr approach proposes the Arts as a rich and effective cultural forum wherein it may be possible to demonstrate and enhance CP’s potential as a creative co-authored process integrated into a wider ecosystem.

Towards a Critical Praxis

With at least eight other definitions of CP currently in circulation (Gadwa-Nicodemus, 2014), there is no single theoretical framework or set of ethical guiding principles in place to inform the ‘how’ of CP. The encouragement of the conditions for adaptive emergent behaviour, important contributors to resilience for addressing systemic vulnerability and diversity, is critical.

Answering the calls from the field (Bedoya, 2013a; Brenner, 2013b; Mehta, 2013; Loflin, 2012; Silberberg, 2013), CP is re-considered as a creative networked co-production re-imagined through an open sourced, situated ephemeral process that trials, adapts and embeds Permaculture design principles into an immersive process, the artist's residency. Drawing attention to materials, activities and actors, an ethos and methods are integrated into bespoke tactical arts projects through an eco-derive; a transferable yet non-formulaic method for Creative Placemaking.

Cultivating permaCultural Resilience

The interdependent relationship between an ecological system and a social system, (an area under researched within CP) guides a localised response, acknowledging planetary urbanisation as a contributor to a complex dynamic. In this context, an interesting question arises as to how CP might best be performed in light of such concerns, increasingly attributed to the Age of the Anthropocene. Through the development of a resilient eco-social cultural system (Waltner-Toews et al., 2003), a dynamic CP process seeks to foster opportunities and avenues for residents and participants to present their narratives of place, defined as intimacy with place. This concept of intimacy with place - a detailed knowledge of a geo-location, including relationships, personal and professional, human and natural is the core resource ASU IR’s method seeks to unlock.

Trialled in UK, Ireland and USA within distinct residency infrastructures the research is an exploration of emergent ideas of OS place-making and the potential of the arts to reveal, recognise, value and integrate the knowledge and expertise that already exists in place. Through building micro-ecologies within the ecosystem of the resulting projects the foundation for sustainable benefits to the residents and the location, a resilient co-authored polyvocal process of creatively making place is established.

Urban Design Studies can no longer be organised by definitive understandings of settlement, i.e. urban, suburban and rural (Brenner, 2013b). Additionally, concepts of social and environmental equity are compromised by the global capitalist system, the profit-driven underpinning of planetary urbanisation. Added to this, the debate around an era increasingly known as the ‘Age of the Anthropocene’ has been strengthened with ninety-seven percent of climate scientists now in agreement on anthropogenic climate change (Cook et al, 2013). This recent shift in scientific evidence and understanding of the impact of climate change has caused corresponding shift in the debate increasingly towards discussion not about the existence or otherwise of the ‘Age of the Anthropocene’, but rather to investigations as to when it can be seen to have begun and issues that will arise as the ‘Earth System’ (Steffen 2015) changes.

Scientists are currently considering key spikes, such as the European arrival in the Americas dated as 1610, the Industrial Revolution, 1760, and ‘the great acceleration’, 1950, all of which dramatically shifted the scale and speed of change. Each of these events has contributed in a variety of ways to the philosophy and process of placemaking, e.g., Spanish colonial architecture and administration, empire building, the economic and environmental impact of industry, internationally and the development of urban clearances and the creation of suburbs. These legacies are visible within spatial design practices, including current CP practices, which can see dominant narratives and professional design approaches shaping and defining the places we make.

Current discussion is further interrogating the concept with theorists e.g. Donna Haraway (2015), Bruno Latour (2014), Andreas Malm, Alf Hornberg (Malm and Hornberg, 2014) and Jason Moore (2011) and terms such as Ecocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene (Haraway, 2015) and positions, the eco-modernist manifesto (Asafu-Adjaye et al 2015). Although not the focus of the research, as a situated practice the research recognised anthropocentric environmental impact and planetary urbanisation as characteristic of the situation in which Creative Placemaking finds itself. CP was considered to hold potential that had not yet been fully actualised, susceptible to economic imperatives or the singular animation of public spaces within the built environment, rather than creatively making resilient places.

An Introduction to Art Services Unincorporated’s Research Approach

ASU in residence (ASU IR) was a strategy evolved as an appropriate tool for work undertaken in a complex, adaptive, environment where singular causality is unsuitable and results must be recognised as intrinsic to the generative process of the given situation and beyond. Through situated interventions, the research addressed two levels of ‘situation’. Firstly, the geo-location’s context within which ASU IR finds itself, and the broader systemic landscape in which both CP and the geo-location are situated and it is important to identify this additional level.

Grounded within an arts research paradigm and a bespoke ‘edge-dwelling’ methodology, ASU IR’s itinerant process, enacted specific contexts, developed a praxis that reflects, embodies and enacts both theoretical awareness and professional skills. This relational perspective explored the benefits of artists’ engagement with systems and environmental inter-relationships i.e. ecological, geographic, political, biological and cultural into CP.

Previous residency experiences had highlighted the potential and frustration of durational engagement particularly, a context-responsive open-ended approach. The onus to produce an exhibition or artwork often frustrated the potential with lines of inquiry drawn to a close prematurely to resolve the process and fulfil residency obligations. Residency conversations considered the disruptive potential of an artist’s intervention as a provocation to re-consider a familiar environment that was often taken for granted or un-noticed. Keen to explore the disruptive potential of the artist as a variable for its contribution to the ethos and practice of CP, ASU IR initiated a formalised exploration.

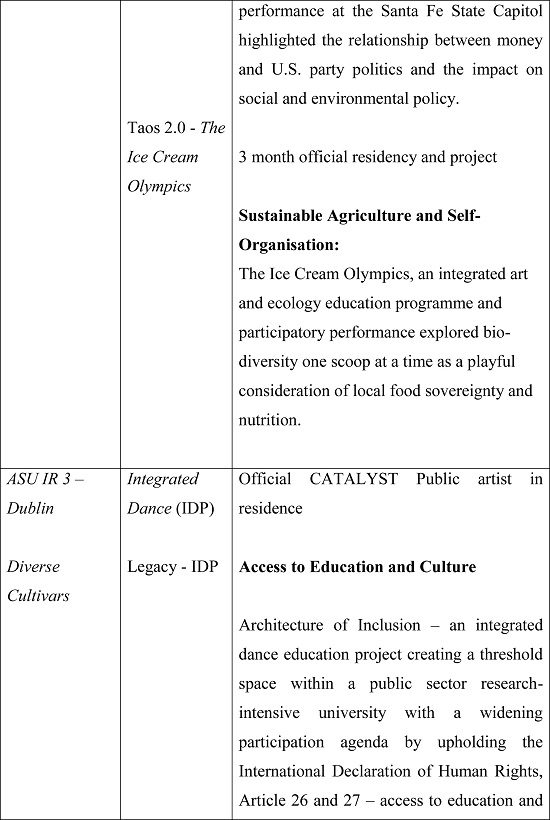

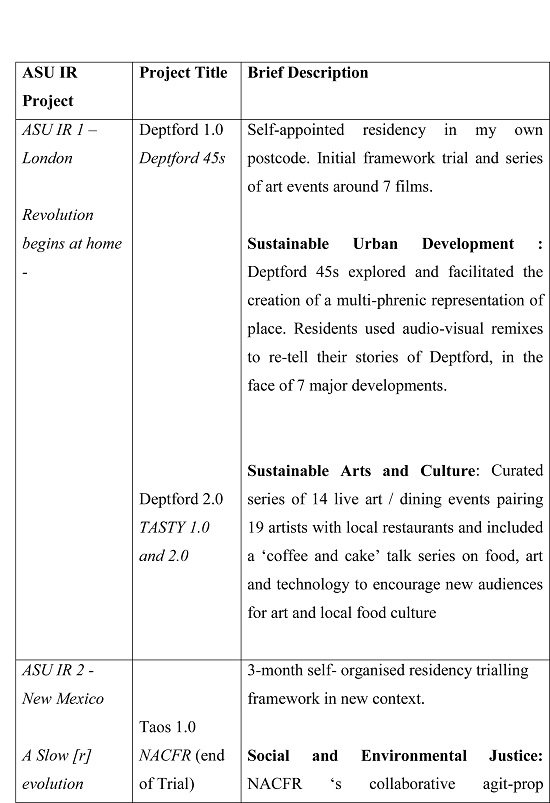

Summary ASU IR 1 – 3 Projects and Local Concerns Explored

An investigation of the Permaculture maxim of ‘the solution lies within the problem’ integrated Permaculture design methods into a situated art practice to create a durational opportunity to consider a tool for problem-finding across a range of contexts. The social and environmental lens inherent within Permaculture is applied through ‘negotiation, connection, collaboration, engagement and participation’ (McGonagle, 2011:44): the emergence of a resilient sustainable practice and processes of Creative Placemaking.

Developing and Adapting Permaculture’s Methods

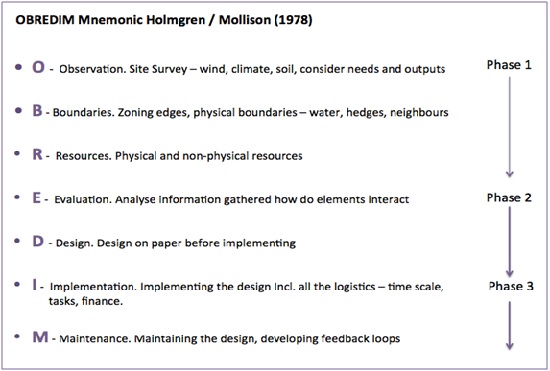

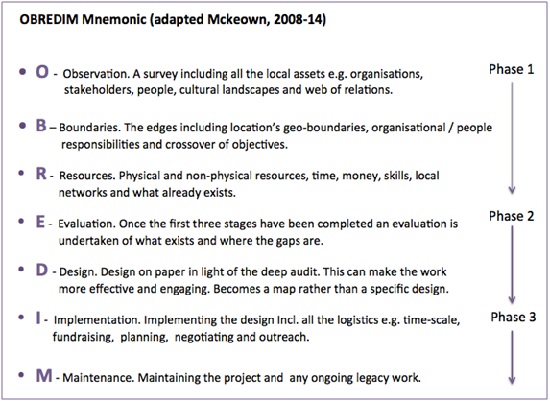

Contemporary Permaculture, was developed and promoted by Bill Mollison and David Holmgren and defined as an ‘integrated, evolving system of perennial or self-perpetuating plant and animal species useful to man’ (1978). Quickly adapted to signify permanent culture, it recognised the importance of social aspects as an integral part of a truly sustainable system that is continually evolving. Permaculture’s permanence comes from a dynamic, generative approach framed within an understanding of an extended ecological time line and long-term perspective.

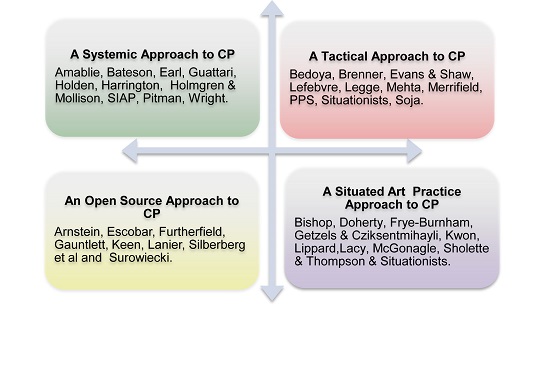

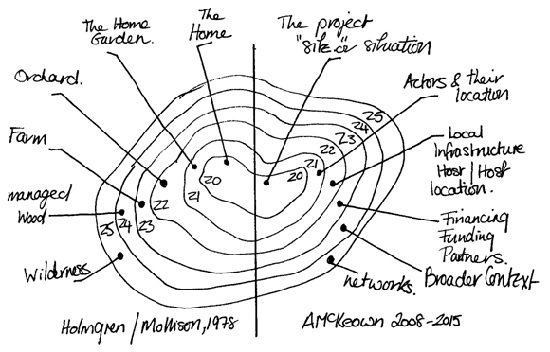

The basic working method, the OBREDIM mnemonic and Zoning (Holmgren and Mollison, 1978) principles became part of a cross-disciplinary ‘living methodology that is the conscious design of ecosystems’ (Holmgren, 2002) in this instance the ecosystem, ASU IR. Permaculture training enabled me to assess the original mnemonic for its benefits for an itinerant artist to begin to ‘see a system’. The original mnemonic OBREDIM refers to physical land-based concerns and used for growing food. This research evolved the concept through its adaption towards exploring its potential for developing a cultural ecology.

Zone mapping also draws attention to scale; further away from the focal point of the project, represents a larger area and consequently more energy / effort inputs are required. Zoning also enables the projects to be considered as cellular in nature, reproducing once capacity has been reached rather than an endless expansion. The cell or project ‘splits’ to form new related projects that can mutually support each other increasing potential of production through developing self-reliance through interdependence. The design principles facilitate the close observation necessary drawing attention to a broad range of inputs contributing to a unique assessment of the location. The zoning in conjunction with the OBREDIM mnemonic provides an intensive ‘audit’ tool to map cultural, economic, socio-political and environmental dynamics.

Depending on the process of engagement and development within various stages; opportunities for group activity, building relationships and contributing to self-reliance and sustainability emerge. On completion of phase 1, OBR and an evaluation, the mnemonic offers a number of alternatives;

- the design, implementation and maintenance of a pilot project

- the building blocks to complete or amend a project

- run the cycle again to consider new opportunities for intervention

The research also incorporates, a simple method of life cycle analysis by further utilising Permaculture’s zoning concepts. By plotting the position of the inputs, processes and outputs of the final art projects’ against the proximity to Zone 0, the residency, an initial assessment of their production process can be considered. Areas of improvement and opportunities for discussion around decision-making whether as to materials, use of suppliers or changes to policy and procedures are highlighted.

Running the project cycle from any point within a sustained artist intervention facilitates relevant project outcomes or if necessary changing course. The OBREDIM mnemonic structures the residency / project activities, providing an itinerant artists’ initial engagement and a solid context analysis tool. This process developed the relationships and knowledge necessary to create a project and its micro-ecologies as a means to draw attention to and initiate possibilities to address localised challenges. As localised public intimacies the project’s micro-ecology facilitates a knowledge exchange, new networks of expertise laying the foundations for on-going communities of practice.

The Zoning aspect of Permaculture highlights relationships between various participants and organisations, and their relationships with physical environments. These relationships are then mapped and integrated into the projects. The ‘site’ mapping process extends out from the central point of the residency, encouraging small-scale actions that reflect the distinct nature of each ‘site’. Zoning organises each ‘site’ into relationships and connections, thereby contributing to the conceptual plan within the evaluation stage of the OBREDIM framework and is project specific. The zones also reflect proximity or intensity in relation to the project and can also include relationships and dynamics of accountability and responsibility. This is an important aspect of the methodology: it is important to recognise an over extension can undermine the projects, and that zonal mapping can highlight areas of concern, and guard against the dissipation of effort.

Conclusion - Cultivating permaCultural resilience

The ‘permaCultural resilience’ framework evolved as an evolution of CP towards a situated networked practice of co-production to facilitate self-organisation and contribute to resilience. The research explored the creation of a ‘road map’ not the road map, simply one possible route, rooted and cultivated by the experience of working in the public domain, on- and offline, within regeneration agendas for twenty years. The initial conceit was an ambition to develop an open-source systems approach to CP by tactically applying permaculture’s audit and zoning methods within a situated art practice to addressing the key challenges for CP – summarised as follows;

- The role of the Arts within planning and placemaking

- Avoiding displacement and gentrification

- Effective sustainable partnerships

- Maintaining and developing legacy projects

- Scepticism (Community and Investors)

- Expectations (Community and Investors)

- Concerns around Capital Spend projects

- Policy / Implementation Regulations

- Evaluation metrics

Embedding Permaculture’s design principles within the constructed situations of the main method ASU IR’s strategic interventions supported an iterative semi-structured improvisation within a location and its complex dynamic. Their construction of ‘temporary commons’ in order to reveal, share, re-mix and disseminate multiple intimacies; place-based knowledge cultures. The integration and adaptation of Permaculture’s design methods supported an immersive durational technique for CP that responded to a local situation, current CP and a global context simultaneously. This enabled the evolution of a guiding framework for an itinerant practice that is non-formulaic and transferable and inclusive of personal and local processes and knowledge.

The research conceived, argued for and trialled a local-scale generative methodology to develop a context-responsive philosophy and practice of CP, one conscious of planetary urbanisation within the Age of the Anthropocene. This expands the definition outlined by Markusen and Gadwa in their attempt to describe CP, identifying and expounding a new and unique process through which it is possible to cultivate permaCultural resilience (pCr) through a CP critical praxis.

The core of the critical praxis proposed cultivates pCr within processual CP through four foundational characteristics summarised as:

1. Building Micro-ecologies: The Arts-led development of networks of praxis to facilitate the revelation of existing knowledge, competencies, capabilites and deficits including local values and concerns within a geo-location.

2. Strategic Intervention Tactics: The identification and re-imagining of opportunities for a broad range of constituents to participate, develop and reveal new avenues of engagement and intervention within local policy and concerns.

3. Re-seeding Local Knowledge: The integration of multiple capitals and knowledge cultures within a socially and environmentally ethical approach that reveals and harnesses latent creativity and opportunities for engagement.

4. Re-situating Arts and Cultural activities: The creation of liminoid (threshold) spaces as temporary commons through Situated Arts Practices through the distruption of normative understanding.

The PCR Vital Signs Evaluation matrix

Within emergent adaptive complex situations, evaluation, just like adaptation is never finished. The results within the pCr approach are the best achievable for that specific situation including time and resources available. The research did not seek to define causal relationships or develop a theory or static model but instead identify a correlation between input and output. The pCr approach strives towards a CP process that enables insights and possibilities that inform future activities rather than fixed solutions: an appropriate goal for an agile systemic approach. Vital signs are indicators to measure a functioning body through the four main vital signs; body temperature, blood pressure, heart / pulse rate and breathing / respiration. From a systemic perspective this offers a viable method to develop an evaluation matrix appropriate to the pCr process. As an ecological approach, the evaluative methods are affirmed by, John Holden’s suggestion to observe vital signs and system deterioration (2015) as a means to determine a healthy generative cultural ecology.

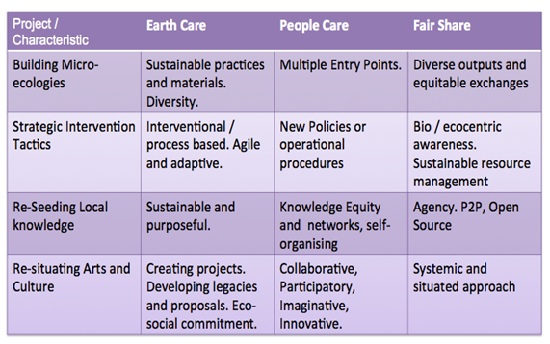

Guided and framed by an Open Source ethos and a Guattarian understanding of Ecosophy that argues for eco-social equity, the permaCultural-dérive - a strategic intervention tactic emerged as a core component for achieving permaCultural resilience (pCr); a situated cultural resilience that is established over time through continual evolution. Informed by the premise of the research and grounded in the concept of vital signs as conventional indicators of a healthy system - human and non-human, the evaluation matrix, constructed through the research uses the proposed foundational characteristics of pCr:

- Building Micro-ecologies

- Strategic Intervention Tactics

- Re-seeding Local Knowledge

- Re-situating Arts and Culture

herein combined with the triad of capitals of Permaculture; Earth Care, People Care, Fair Share (Mollison and Holmgren, 1978).

As a means to measure vitality (revitalisation is a key measure within CP), ASU IR’s ecosystem’s vital signs are also aligned to the four characteristics the research proposed as necessary for permaCultural resilience. The proposed matrix includes these characteristics as necessary for a generative resilient CP process within a complex system to help define or develop the aims or processes of legacy projects including deterioration. It should be noted that the matrix can also be used at the beginning of a project to aid the self-determination of measures. This simultaneously offers an evolutionary path for a project and consideration of measures that indicate the robustness project’s system through the generation measures of vital signs from within (Holden, 2015).

The process of engaging and devising in each project leads to the identification of outcomes and outputs, which can then be measured against a list of ‘vital signs’; indicators of the project and its micro-ecology’s vitality and health. In the case of the ASU IR project, the indicators of vital signs included:

1. Legacy projects and counterfactual perspectives e.g. identifying what would happen if the intervention did not occur – TASTY! Albany residency, Taos 2.0 building on Taos 1.0

2. Economic activity e.g. local hires and youth training

3. Development of legacy networks e.g. Questa coalition and Pecha Kucha Taos partnerships with LEAP

4. Increasing an understanding of the potential of non-object based art.

Adaptation of Bill Hamilton’s Inclusive Fitness Theory (1964) led to another useful metric of impact for the project. Hamilton’s radical concept challenged the field of Behavioural Ecology by repositioning the longstanding polarised discussion around the Bergen / Edwards concepts of the development of behaviour for the good of the group or the good of the individual. Hamilton offers a third option; a gene’s survival is insured not only through direct descendants but also in supporting relatives who may also share the gene.

Usually applied within a genetic understanding health or fitness is not only determined by proliferation of genes in a number of offspring but also the proliferation of genes within their relatives i.e. the dispersal of the genetic code. This becomes a potentially useful concept for evaluating ephemeral participatory artworks, including behaviour they may encourage or traits they may display. Hamilton’s theory aids the identification of ASU IR’s vital signs through networks, relationships established or any legacy projects. This is then evidenced by the dissemination of their ethos, approach ideas or information seeded through on-going projects.

In Summary

As an operating system, pCr presents an Open Source resilient approach to CP, that is deeply political, highlighting and addressing inequities and vulnerable points in a system where alternative approaches can take root. Through Arts-led experimentation the means of piloting new ways to communicate and interact within a geo-location forms the basis of a continuous re-shaping of the physical and social character of place. This in turn initiates and facilitates locally scaled self-organisation towards potential possibilities grown from the inside-out. Incorporating Permaculture into CP’s praxis frames objectives and outcomes of the intervention at an early stage, creates an open-endedness that allows a dynamic response.

Embedding an eco-social equity into CP’s process develops open-source participation beyond conventional hierarchies e.g. spatial planning, development and built environment infrastructure. The integration of art and politics through a systemic and ethical approach to re-interpret the concept of ‘the personal is political’ (Hanisch, 1970), where the personal is extended to acknowledge interdependence.

Introduced as an embryonic framework and practical method to harness an artist’s and others’ skillsets within a ecological analysis of a location, the permaCultural dérive at the core of the pCr approach, grounds these skills within an active process of revealing, valuing and disseminating multiple knowledge cultures. The temporary commons the pCr process creates harnesses the agility of an edge-dwelling (Holmgren, 1992) position to navigate and temporarily inhabit multiple locations simultaneously: geo-locational, operational, social, professional and personal. As a strategic intervention tactic; cross-pollination, an essential characteristic for the third condition of permaCultural resilience, Re-seeding local knowledge occurs.

As a process of arts engagement, the permaCultural dérive encourages a broader constituency of participants into a project’s micro-ecology, establishing new working relationships. As a generative process, the project ecologies’ knowledge is infused into the projects and their knowledge networks. This extended the project’s life span through fostering emergent ideas within on-going partnerships that began to adapt existing working practices and support emergent behaviour. Nurtured through a durational immersive process and location, a lack of fixity and agile response offers a dynamic mutable space to initiate, encourage and accommodate localised action.

Their navigation of a dynamic socio-cultural environment facilitates the gathering of a diverse range of data through a deep audit that encourages a rich engagement with the ‘software and hardware’ of a location’s ecology. This encourages a more nuanced understanding of microclimates, political and administrational relations as well as identifying gaps or opportunities for intervention. The project ecology operates as micro, complex adaptive change systems, merging public and private systems, thereby demonstrating emergent behaviours: e.g. self-organisation, non-linearity, unpredictability.

As a micro-change model the ability to imagine a different world (Peake, 2010) begins to emerge, enhanced through sharing local knowledge and understanding conveying different worldviews or perspectives within a location. Their small gestures become leverage points that encourage greater impacts by transcending conventional or average responses. A dialogical approach is crucial. The creation of resilient enclaves that facilitate the flow of larger systemic processes to bypass unaltered is to be avoided. The concern being that this could sustain such processes through equipping residents with a resilient approach to change that ultimately contributes to the resilience of a dominant narrative.

The permaCultural dérive’s creation of bespoke interventions acts as means to stimulate the flow of information contained within a localised dynamic environment. Through an on-going awareness of a localised system, distributed knowledge networks and their intersubjective, interdependent responses, form a threshold space of potentialities. Their ‘in-between’ states; locale, professional roles, emergent projects and unique re-constructions of space|place|time, confronts many assumptions around the geo-locations in which they are enacted.

Within the pCr process, an Arts-led approach is used to develop micro-ecologies and facilitate the cross-pollination and integration of existing local knowledge and expertise. The knowledge synthesised is represented in accessible forms and explored in tangible ways and deployed within catalysts that seek to affect change: whether a change in perception, knowledge, process or behaviour. As an ecological approach to art-making and in turn a contribution towards ‘leveraging the power of arts and culture for Creative Placemaking’ (Artscape Executive Team, 2010), the process also leverages the power of diversity, an important concept for ensuring the healthy vital signs of an ecosystem.

In the ‘century of the system’ (Gawande, 2014), no single individual can change or be expected to change whole systems, their policies or procedures. The potential value of the concept and practice of permaCultural resilience is in the development of socio-cultural ecologies of participation that are imaginative, creative and equitable. The exploration of engagement with multiple capitals and knowledge cultures was developed on a local scale to encourage self-organisation for resilience.

As an approach it is scalable i.e. can be expanded or reduced as required. Indeed, recognition of resources and their limitations is a key aspect of the method. This attention to resources and boundaries including inter-agency engagement as well as investment and further evaluation will be necessary if the value of the approach is to be applied on a larger scale. In keeping with the pCr ethos, the framework is a temporary landing stage, complex and emergent, to be further interrogated and evolved as the methods presented have limitations, seeking only to contributes to the vibrancy of an existing ecosystem rather than displacing or overshadowing the local context. Instead pCr seeks to encourage everyone as a Creative Placemaker through the aspiration to make resilient places creatively and:

Re-situate Arts and Cultural practices to lead the building of cross-sector micro-ecologies that develop strategic intervention tactics to re-seed local knowledge, specialist and non-specialist, to creatively make and re-make dynamic resilient places

*

Anita McKeown FRSA, PhD is an interdisciplinary artist, curator and researcher working in the public domain. Her work in the main is project-based, context-responsive, ecologically sensitive interventions that arise from extended relationships within a location. Her wider research interests include Open Source Culture and Technology (ethically and ecologically) and STEAM education. Her recent research (2015) explored emergence and self-organisation within Creative Placemaking, through the development of a bespoke systemic framework including a practical toolkit piloted in the UK, Ireland and USA.

[1] Art Services Unincorporated (ASU) established in 2004 is the collective identity for an on-going practice that represents the multiple contributions that contribute to ASU’s process of producing artwork. Art Services Unincorporated in Residence 1- 3 (ASU IR 1 – 3) was the main vehicle used to develop the permaCultural resilience approach to Creative Placemaking.

[2] The research drew on original economic research and fourteen case studies that ‘summarised twenty years of creative American placemaking’ (NEA, 2010) guided by recommendations from national experts within the fields of the Arts and Culture.

Bibliography

4 Culture (2007) Southeast False Creek Art Master Plan, Vancouver, Canada: Buster Simpson. The Challenge Series Available at: http://www.thechallengeseries.ca/chapter-03/place-making/#unpredictable Accessed: 17/10/2010

Asafu-Adjaye, J., Blomqvist, L., Brand, S., Brook, B., De Fri Es, R., E L L Is, E., Foreman, C.,Keith, D., Lewis, M., Lynas, M., Nordhaus, T., Pielke Jr, P., Pritzker, R., Roy, J., Sagoff, M., Shellenberger, M.L., Stone, R., Teague, P. (2015) The Ecomodernist Manifesto Available at: www.ecomodernist.org Accessed: 7/5/2015

Bedoya, R. (2013a). Creative Placemaking and the politics of belonging and disbelonging. Available at: http://www.worldpolicy.org/blog/2013/05/13/creative-placemaking-and-politics-belonging-and-dis-belonging. Accessed: 15/1/2014

Bergstom, C, (2012) Interviewed by Brian Goslow in Artscope Nov 1 Available: http://zine.artscopemagazine.com/2012/11/cornered-extra-christopher-kip-bergstrom/ Accessed 15/1/2013

Brenner, N. (2013b), ‘Place, Capitalism And The Right To The City’. Oct Keynote Lecture, Creative Time Summit. New York City.

Brenner, N and Schmidt, C. (2014) ‘The Urban Age in Question’ International Journal of Urban and Regional Research Vol 38, Issue 3, pages 731–755, May 2014

Coletta, C (2010) Lets Talk Creative Placemaking, Available at: http://arts.gov/art-works/2010/lets-talk-creative-placemaking (Accessed: 15/3/2011).

Cook, J., D., A Green, S.A., Richardson, M., Winkler, B., Painting R., Way R., Jacobs P. and Skuce, A. (2013) ‘Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature’. Environmental Research Letters Vol. 8 No. 2, (June 2013)

Dakin S, (2003a) ‘There’s More To Landscape Than Meets The Eye: Towards Inclusive Landscape Assessment In Resource And Environmental Management’. The Canadian Geographer/Le Géographe canadien, 47(2), pp.185 – 200.

Debord, G. (1988) Comments on The Society of the Spectacle. London: Verso

Florida, R. (2002) The Rise of the Creative Class and how it's transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. Basic Books, New York

Gadwa-Nicodemus, A. (2012) ‘Creative Placemaking 2.0’ in GIA reader Vol 23 (No 2), Available at: www.giarts.org/reader-23-3 Accessed: 31/1/2013

Gadwa-Nicodemus, A. (2013) ‘Fuzzy vibrancy: Creative placemaking as ascendant U.S.’ in Cultural Trends July 2013. Taylor Francis Available http://www.tandfonline.com/10.1080/09548963.2013.817653 Accessed: 17/5/2014

Haraway, D (2015) ‘Commentary Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin’. Environmental Humanities, vol. 6, 2015, pp. 159-165

Harvey, D. (1989) The Urban Experience. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press

Krishnamurti, J., (1973) The Flight of the Eagle: An Authentic Report of Talks and Discussions in London, Amsterdam, Paris, and Saanen, Switzerland, London, UK: HarperCollins Publishers.

Landesman, R. (2009) Keynote Speech GIA conference, Navigating the Art of Change, Brooklyn NY.

Landry, C., Greene, L., Matarasso, F., & Bianchini, F. (1996), The Art of Regeneration: Cultural Development and Urban Regeneration, Comedia in Association with Civic Trust Regeneration Unit, London and Nottingham City Council.

Lanham, KF (2007) Planning as Placemaking; Tensions of Scale Culture and Identity. Virginia. Available at: http://www.ipg.vt.edu/papers/klanham.pdf [Accessed 20/7/, 2011].

Latour, B (2014) Agency at the time of the Anthropocene New Literary History

Vol. 45, pp. 1-18, 2014 Accessed: 18/12/2014

Lefebvre, H (2003a), (Eng Trans) The Production of Space, Blackwell Publishing, Liphook, Hampshire, UK.

Loflin, K / Gallup, Inc. (2012) ‘Soul of the Community in 26 Knight Foundation Communities in the United States 2008-2010’ Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research

Malm,A. and Hornborg, A. The geology of mankind? A critique of the Anthropocene narrative The Anthropocene Review Vol 1, Issue 1, pp. 62 - 69 January-07-2014

Markusen, A (2014). Annual Sir Peter Hall Lecture 2014 - Creative Placemaking Revisited: A Forward-looking Research Agenda. Bartlett school of Architecture, London, May 2014.

Markusen, A. and Gadwa, A. (2010) ‘Arts and Culture in Urban/ Regional Planning: A Review and Research Agenda’ In Journal of Planning Education and Research 29, no. 3: 379-391.

Markusen, A. and Gadwa-Nicodemus, A. (2010) Creative Placemaking A White paper to the Mayor’s Institute of City Design, Washington, D.C. National Endowment of the Arts.

Matarasso, F. (1997) Use or Ornament: The Social Impact of Participation in the Arts, Stroud: Comedia

McKeown, A. (2015) ‘Deeper, Slower, Richer: a slow intervention towards resilient places in Placemaking’ in Edge condition Vol 5 Jan 2015 p24 - 27 Available at: http://www.edgecondition.net/uploads/9/5/5/6/9556752/edgecondition_vol5_placemaking_jan15.pdf

Meadows, D.H., Meadows, D.L. Randers, J., Behrens, W.W. (1972) Limits to Growth A report for The Club of Rome’s project on the Predicament of Mankind. NY: Universe Books

Meadows, D. H. (2008) Thinking in systems: a primer. Vermont: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Merrifield, A. (2009) The Politics of the Encounter: Urban Theory and Protest under Planetary Urbanization. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

Mehta, N. (2012) The Question all Creative Placemakers should ask. Available at: http://nextcity.org/daily/entry/the-question-all-creative-placemakers-should-ask [Accessed June 14, 2013].

Mollison, B. & Holmgren, D. (1978) Permaculture One: A Perennial Agriculture for Human Settlements Tasmania: Tagari Publications

Moore, J (2011) Ecology, Capital, and the Nature of our Times:accumulation & crisis in the capitalist world-ecology accessed: 21/3/2014 http://www.jasonwmoore.com/uploads/Moore__Ecology_Capital_and_the_Origins_of_Our_Times__JWSR__2011_.pdf

Silberberg, S. et al, (2013) Places In The Making: How Placemaking Builds Places And Communities Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Soja, E. & Kanai, M. (2005) ‘The Urbanization of the World’ in R. Burdett and D.

Sudjic (eds.) The Endless City. New York and London: Phaidon; 54-69

Swyngedouw, E. (1992) ‘The Mammon Quest: 'Glocalization', Interspatial Competition and the Monetary Order: The Construction of New Scales’ in ed. Dunford, M. & Kafkalis, G, Cities and Regions in the New Europe: The Global-Local Interplay and Spatial Development Strategies, p39 - 67. London: Belhaven Press

Vazquez, L., (2012) Creative Placemaking: Integrating Community, Cultural and Economic Development. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2474862. Accessed 17/11/2012

Waltner-Toews, D., Kay, J., Neudoerffer, C., Gitau, T. (2003) ‘Perspective changes everything: managing ecosystems from the inside out frontiers’ in Ecology and the Environment 1(1):23-25.

Zukin, S. (1988) Loft Living: Culture and Capital in Urban Change. London, UK: Radius.