Dec. 10, 2014

Contestative art from Southeast Asia

Three Significant Exhibitions of Southeast Asian Contemporary Art that Shape the Region's Canon

Written by Bharti Lalwani

In the year 2000, Thai artist Sutee Kunavichayanont lined rows of fourteen school desks and chairs at the foot of Democracy Monument in Bangkok. Out in the open, the installation History Class (Thanon Ratchadamnoen, 2000), seemingly innocent in its scope, invited members of the public, Thai, non-Thai alike, to sit at these desks and make pencil-on-paper rubbings. In doing so, the public was to discover the contentious messages inlaid within the desks' etched surfaces. Illicit chapters of Thailand's past - People's uprisings, student protests, assassinations, military crackdowns, and torture- not discussed in school textbooks or written out of Thai history, revealed themselves on paper-rubbings which the participating public then took home.

Co-opting the public, enticing them to confront questions of citizenship, to consider individual responsibilities and their consequences for the collective, is one of the tactics that were extensively explored in three recent landmark exhibitions on SEA contemporary art:

- Negotiating Home, History and Nation: Two decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia, 1991-2011 curated by Iola Lenzi in collaboration with Tan Boon Hui and Khairrudin Hori at Singapore Art Museum (SAM), 2011

- Concept, Context, Contestation: Art and the Collective in Southeast Asia

curated by Iola Lenzi in collaboration with Agung Hujatnikajennong and Vipash Purichanont at Bangkok Art and Culture Centre, 2013

- The Roving Eye: Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia

curated by Iola Lenzi at ARTER, Istanbul, 2014

History Class and its recent extension History Class II (2013) anchor all three exhibitions, arguably embodying canon-inflecting attributes of Southeast Asia art: formally appealing, interactive, audience involving, borrowing codes from millennia-old culture materially and conceptually, performative, tactile, playful yet contestative. Formally alluding to anonymous wood-carving village-craft, this interventionist installation draws on the public's collective childhood memories and experiences as supine students of history. As visitors begin to engage, their attention is inevitably brought to what the etchings reveal. With this crucial interactive strategy, the art activates its passive viewers into considering broad questions on authorship of history, identity, state-education systems and nationalist propaganda. While purposing a forceful involvement with audiences in the public sphere (as opposed to being in a white-cube setting), Sutee's allusive approach would be dormant without audience-reception. Were it not for the ordinary public taking home revelatory chapters of contentious cases in Thai history, this artwork of political, social of cultural concerns would remain latent.

The genesis of contemporary art practices of Southeast Asia (SEA), largely viewed in relation to China, India or Asia Pacific, were for the first time examined within their own historical circumstances. In Negotiating Home, History and Nation (NHHN), 54 seminal artists, pioneers of their field, from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam were brought together by the regional institution, effectively mapping SEA art practices over two decades. Through over 70 artworks that encompassed photography, video, paintings, performance and installations, what became apparent was SEA artists' ability to deploy their agency.

According to the curator and specialist of Southeast Asian art, Iola Lenzi, her goal was to illuminate some of Southeast Asian contemporary art’s key traits. "The work had already been started by Apinan Poshyananda in his Asia Society show ‘Traditions Tensions’, said Lenzi, 'but what was only just emerging in 1996, was much clearer fifteen years later and therefore could be synthesised. I deliberately included two works from Tensions in the show at Singapore Art Museum (SAM) – Dadang’s terra cotta heads, and Nindityo’s opening konde tables – as a way of referencing this exhibition lineage. In my curatorial essay for NHHN I set out what I saw as the master themes and approaches of regional art, the works in the SAM galleries corroborating. Concept, Context, Contestation (CCC) and Roving expanded on specific aspects of the field."

Regarding their roles as critics, artists directly or indirectly addressed themes of nationalism, empowerment, sexuality, inequality, marginalisation and repression through the course of nation-building in Southeast Asia's young and as yet formative democracies. Artists such as Vu Dan Tan, Lee Wen, Heri Dono, Amanda Heng, Wong Hoy Cheong or Nguyen Van Cuong were not simply presenting literal depictions of cultural, economic and political transformations ushered in by Reformasi in Indonesia, doi-moi in Vietnam and by pre and post Asian Crisis of the late 90s in Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore and Philippines. Rather, they positioned their art so as to address ethnic tensions, social injustices, racially biased policies and unbridled greed and consumerism through query, metaphoric allusion and appropriation. This combative streak asserts itself clearly in the following exhibition Concept, Context, Contestation. If NHHN attempted to frame an amalgamation of SEA art practices, then CCC expanded on one of former exhibition’s key currents- Conceptualism grown out of local context.

Once again, examined not within the ambit of Euramerican post modernism, CCC included a different set of artworks by early innovators as well as younger artists from Thailand, Indonesia, Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Burma and Cambodia. An exhibition concept Lenzi had been mulling over for a decade, CCC untangled and extrapolated certain ideas from NHHN, primarily, how artists in Southeast Asia deploy conceptual strategies to make their work function. As per Lenzi, 'The deliberate aspect of these tactics whereby form, medium, space, aesthetics, pre-existing languages, are enlisted, indeed orchestrated to produce art with social agency."

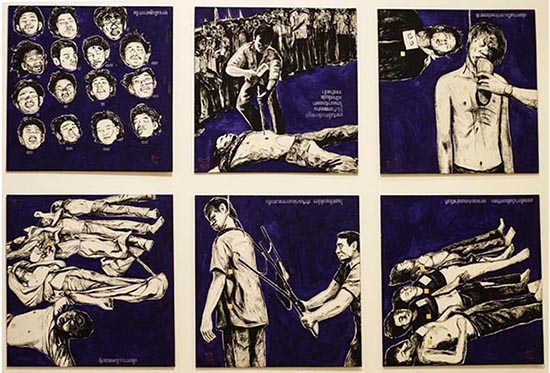

CCC illustrated the connections between locally-rooted conceptual approaches and social ideologies in Southeast Asian art of the last four decades. The earliest artwork remade for this exhibition was FX Harsono’s Pistal Krupuk Semoga Menjadi Piatal Beneran (What would you do if these crackers were real pistols?). Originally made in 1977, in this work Harsono piled pinkish edible gun-shaped rice-crackers on the gallery floor. In a diary placed on a desk beside this cheerfully coloured mound, visitors could record their responses to the piece. Pistal Krupuk Semoga Menjadi Piatal Beneran evolved from the steady clampdown on criticism of President Suharto’s authoritarian regime (1967–98). As is the case with Sutee's desks, Harsono's wafer-guns directly address the public, activating them as catalysts for social change. Taking a more codified approach to critique was Blue October (1996) by Thai artist Vasan Sitthiket. A set of six paintings, Blue October references the 1976 Thammassat University massacres. Icy cobalt-blue surrounds monochrome scenes of brutality borrowed from media images of the day. Deliberately uncomfortable in their violent iconography, these stark paintings go for forceful confrontation with the public but at the same time are irrefutably seductive to the eye. On close examination, small squares of gold leaf appear on the shoulders of the dead, marking them as martyrs. The gold-leaf, an allusion to merit-making in Thai Buddhism, is a symbol legible to Southeast Asians. Re-contextualized, grounded in reality, this act of appropriation and reference makes up the conceptual core of the work. Blue October illustrates how regional artists combine conceptual approaches and powerful images related to local issues to rope the public in.

CCC especially highlighted SEA artists' ability to engage the public through shared experiences, probing our national and cultural identities and the basis of their fomentation. Amanda Heng's seminal 1996 performance recreated here, tackled language politics. Singapore's 1979 ‘Speak Mandarin Not Dialect’ policy informs the social bean-sprout cleaning in Heng’s Lets Chat. The policy, meant to unify the Chinese communities of Singapore by strengthening a single national language, inevitably robbed independent communities of their cultural identities and also prevented the younger generation from communicating with their elders. A product of the successful campaign, the young Heng was left with no linguistic skill to communicate with her dialect-speaking parents. This traumatic experience, shared by many of her generation, left her devising other forms of connection. Through her invitation to audiences to embark on the routine chore of cleaning sprouts, Heng’s work reveals how she expands from the personal to address the communal. As with the illicit chapters etched on Sutee's desks, artists Harsono, Heng and Vasan pique old but unhealed wounds inflicted during the latter part of the twentieth century. By forcing the common public, otherwise preoccupied in consumerist pursuits, out of their selective amnesia, they make possible a discussion on controversial events never discussed within national narratives and state-controlled agendas.

Sited in Istanbul, The Roving Eye, third in the exhibition-trilogy, matured yet another key strand- the notion of Southeast Asian art’s evolving viewpoint. Lenzi observes, 'There are many more exhibitions to be constructed exploring regional art’s central themes and ideas. These feature in work produced by a younger generation of regional artists, so proving that these inflections are indeed central to Southeast Asia's art-historical canon."

For sure, these socio-political concerns are not just limited to the pioneer artists but include artists of later generations as well, their practice influenced by their own local, cultural and historical contexts rather than by Duchamp, Bueys or Warhol.. Employing similar strategies in The Roving Eye are younger artists- Bui Cong Khanh, Tay Wei Leng, Jakkai Siributr and Ise Roslisham, Yee I-Lann, Josephine Turalba, Chris Chong Chan Fui, Vertical Submarine, alongside their more established peers- Dinh Q. Le, Jason Lim, Melati Suryodarmo, Alwin Reamillo, krisna Murti, Mella Jaarsma, among others.

While NHHN and CCC were highly accessible in their reading to, and deliberately for, Southeast Asian audiences, Roving Eye, making its first foray into Europe, tested the legibility of SEA-centric concepts to the Turkish public. With over forty works from Indonesia, Thailand, the Philippines, Singapore, Myanmar, Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia, The Roving Eye suggested a restless oeuvre. Playing on perspectives as victim/oppressor or ethnic minority/majority simultaneously, Southeast Asian artists illustrated their unstrained ability to communicate philosophical questions on ongoing conflicts the world over.

As artworks exuded formal brio typical of SEA artists, their art-objects and performances operated as powerful multi-layered critiques on political oppression, authoritarianism, environmental devastation, religious extremism, rising xenophobic tendencies, social exclusion and transcultural flux. Borne out of pathos for the collective-at-large, such pertinent themes hence transcend beyond linguistic and cultural barriers through visual and interactive cues to unravel officially established concepts. The Roving Eye received well over 10,000 visitors within its opening fortnight. A record high for any exhibition at ARTER. Having seen the exhibition, Dr. Amin Jaffer, (International Director of Asian Art, Christies) observed, "The commentary on servitude and migration, notions of loyalty to the state, monarchy, government all come though very clearly. The question of ethnicity and multi-culture is indeed a big one, for Chinese or Indians or any of us migratory people to consider."

SEA artists, while deploying their primary strategy place viewers front and centre. As they communicate through visual form, query, humour, interaction and playfulness, they do so in order to empower the individual into raising his or her voice so as to be heard in the face of repression. Indeed many Turkish visitors who coloured away at Sutee's desks, felt inspired to look into their own nation's history, making connections parallel to SEA, especially considering the events that have transpired since the beginning of the Arab Spring. Roving Eye, hence proving that Southeast Asian artistic expression can translate flawlessly to audiences around the world.

Bharti Lalwani is an art critic who contributes to The Art Newspaper, Harper's Bazaar Art Arabia, Eyeline (Australia), and Asia-Europe Foundation's portal Culture360.org, among numerous international art journals. Her research interests include Private museums as well as contemporary art from Southeast Asia, the Middle-East and West Africa. Through her writing and research she connects the emerging contemporary art histories of three continents. In 2014, she was nominated Forbes Art Writer of the Year (India). Currently she has been nominated from Singapore, Thailand and The Philippines for Best Writing on Asian Contemporary Art for The Prudential Eye Award.

Bharti Lalwani has an MA in Contemporary Art from Sotheby's Institute (Singapore) and a BA in Fine Art from Central Saint Martins (London).