July 6, 2014

Conversation with Wanda Raimundi Ortiz and Ivan Monforte

Written by Rocío Aranda-Alvarado

This conversation occurred at El Museo del Barrio, an art institution founded in 1969 in East Harlem, during a period of political and social change by the Puerto Rican artist/activist Raphael Montañez Ortiz. Both Wanda Raimundi Ortiz and Ivan Monforte have been included in El Museo’s biennial exhibition, La Bienal (formerly The S-Files). Their bodies of work intersect in terms of their approaches to dealing with gender, race and class. The discussion evolved into an exploration of larger issues around the exclusion of artists or censorship of their work that deals with specific issues. In some cases, the will to restrict freedom of expression comes from unexpected places, including the community from which the artist originates. Struggles with identity for both artists are born from a problem of finding a place within the metanarratives of art history and within contemporary practice as embraced by mainstream institutions. Though they make work that is applicable to wider audiences, they are often restricted to exhibitions or discussions that explore a particular subculture or an ethnically specific group. Here, we discuss some of the works they have made that have been censored or have been the target of a variety of social anxieties.

RAA: Pain, suffering, isolation seems to inflect both of your bodies of work in some way. This is true for the art of many artists of color working in the United States from the end of the 20th century through the contemporary period. Can you discuss the role of pain in your work and how it might be influenced in some way by social censorship?

IM: For me pain is physical and emotional. One of my favorite things is stigma, because it’s an opportunity to discuss things that are very real and look at where the culture is. And culture is constantly shifting. Pain also bonds us in a way that other things don’t. My video Sorry (2006) was about addressing the fact that in many ways we are all the walking wounded. We are all either waiting to make an apology or waiting to receive an apology. If you watch the video long enough it is really about seeking your apology. Pain is in some ways universal, we all suffer. It’s the reason I’m drawn to the work of Frida Kahlo, like when I was a teenager. Or why I’m drawn to the work of someone like Joel Peter Whitken and other extreme artists. I was lucky to get the kind of education that I did. I had professors in my undergraduate courses that were unafraid to explore these topics that elsewhere might be censored. My first video teacher was Paul McCarthy, we used to refer to his class, New Genres, as “nude genres.” For me, I rehearsed a certain reality…I am from a particular place, a particular time, of a particular experience, so that’s the work that I make. In one of my first videos, I was dressed as cholo, but doing everything wrong…I’m dancing the wrong way, playing with a cat, taking a bubble bath and in the final scene I’m putting makeup on my face, and McCarthy’s said that he was nervous because he was wondering how far I was going to take it. So I felt that I was doing something right…

WRO: But you were doing it in a very quiet way.

IM: Yes, in fact, I’ve been told that my work is like a snowstorm, something that begins very quietly and suddenly you have fallen into the work and you can’t get out of it. It makes people shut down, because its too painful. I did this project where I was mapping emotions, documenting people going from extreme joy to extreme sorrow. I hired an actor who I asked to go from laughing to crying in one take, I asked a friend to sing songs that make him feel the happiest and the saddest, and I asked another friend to just think about the happiest and saddest moments in her life, and I recorded their reactions as art.

Art is anything at this point. But to make work that really affects viewers, that makes them pause and think about an experience is important. My role as an artist is to help push things forward, especially things that are difficult and really heavy things. In the past, these were artists’ secret projects, things they made on their own without expecting support. But now, it doesn’t have to be a side project. We grew up in the 90s, so the topics were race, gender, sexuality, HIV, everything had to be discussed.

In the end, pain, emotion, struggle, these are all part of human life, and we are not different, we share the same experience on this planet in different ways. I bear witness to people’s traumas and understand that we all, as humans, deal with that trauma that we experience. I think it is also about the experience of being undocumented until I was 14, my being invisible, bearing witness to own family’s struggle and trauma, and struggles even within the family. Part of it is a reflection of us being poor and of color. My parents both have one indigenous parent and one white parent. We grew up speaking Spanish, English and Maya. There is strong stigma associated with being indigenous in Mexican culture. I have shared dinners with Mexican elites of the art world, who have not recognized me as Mexican, which I tell them makes sense because those who look like me are usually the help, the domestic workers or laborers.

RAA: Wanda, how has pain inflected your work? I feel it was particularly prevalent in some of your endurance works that you created while still in school, but also in very subtle ways in works such as a video in which you changed your look from someone who could pass for Anglo, to a very clear version of “Latina” beauty.

WRO: I’ve talked before about being ni de aca ni de alla, from neither here nor there, not light enough to be included in the mainstream of “gringolandia,” or the Anglo world, and not dark enough to belong in the black community. It’s come to my attention that I’m “not black enough.” It’s strange to hear that from a community that does not want to be ostracized. I always wanted to be a graffiti writer, but I was too protected by family. This idea of not being enough of any one thing or another forced me into a weird fractured state, and in that fractured state I found myself constantly having to validate my presence within either the Anglo group or the black group in high school and then again art school. I was constantly harassed by others from the neighborhood, who were trying to censor parts of my identity that did not fit into a South Bronx aesthetic. So I learned to turn weakness into strength. I figured, if I can’t win, I’m going to lose big. I learned to use this outsider status as an attitude. I took comfort in carrying my giant portfolio around with me, in being different.

Perhaps the earliest point of pain was the death of my father, when I was only 11. Pain worked itself into my practice, as I was trying to find a space for myself, in the fractured state between these two worlds where my boricuaness (Puerto Ricanness) met my artsy gringa (Anglo) whiteness. The art world meant whiteness, and I never saw myself in the art world. I could picture myself doing sketches for the courthouse or for newspapers, but it was a very blue-collar way of looking at making a living from art. I faced the reality of not fitting in anywhere, but I saw how this afforded me an opportunity to learn how to communicate differently with different communities. I learned to speak one way around white kids and another way with the black kids, and I became a kind of a conduit.

My first major work was at the Bronx Academy of Art and Dance. I wanted to honor my mother; I created a split stage, where I represented my life with my husband on one side and my studio on the other. He always endorsed my creativity. But even in that space, I struggled with being a Puerto Rican wife and being an artist at the same time. There are certain things you don’t say, you self-censor. You protect your image and your reputation. I worked in moments when my husband was sleeping, or away, keeping my practice very private, to make sure that it didn’t impinge on our married life in any way. Because of that, I fell backwards into this identity practice. It comes from trying to figure out who I was and where I fit into the larger culture

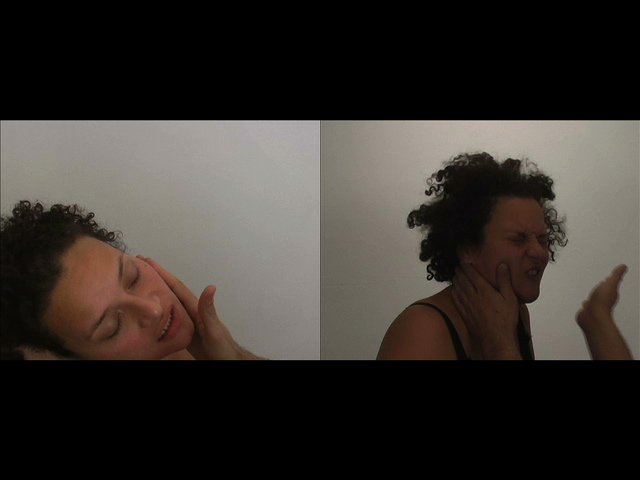

RAA: I wanted to ask each of you about specific works in which some of these issues are present in revelatory ways. Wanda, your endurance work in which you are slapped repeatedly by male hands, titled Until its Quenched and Until it Breaks. This made a huge impact on me when I saw it, particularly because of the nature of the actions, the redness visible on your face. And Ivan, your video Que te Vaya Bonito I think is a wonderful example of the impact of displaying “forbidden” emotions in performance and video.

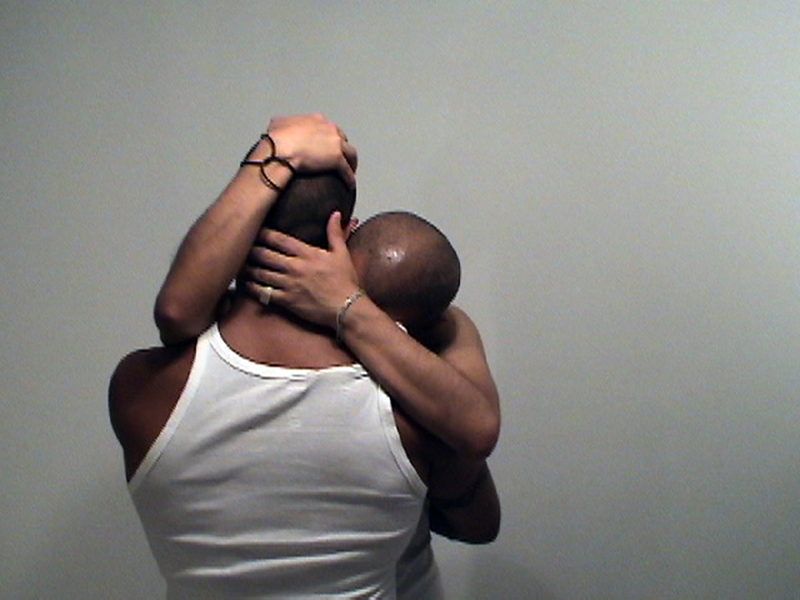

IM: Que te vaya bonito, is my homage to Mexicans. Being included in El Museo’s Bienal was the first time the work was going to be read within the context of Latino culture. This work was the culmination of two projects, Untitled (I’m just trying to show you/K-12), only to be exhibited in non-profit or museum spaces where kids have access to the work. It was about providing imagery to young people about gay intimacy that was not hypersexual. It was really about two humans being intimate with each other, not necessarily about sex. We slow dance, we cuddle and I make out with a guy, acts that are often censored in popular culture. In same the series there are other acts typically censored also, as when someone sucks my neck to make a chain of hickeys or kiss marks, or Tres veces, in which I receive blow jobs from three different men, based on a Paquita la del Barrio song, Tres veces te engañé. The gestures in the video performance are about flipping sweet intimacy and looking at the painful aspects of being in relationships. In Que te vaya bonito, I drink an entire bottle of tequila, while a song about breaking up by Chavela Vargas is playing and I begin to cry. The work was about addressing the idea that within Latino culture, men are not allowed to cry or show emotion. They are allowed—encouraged even—to be angry, because this shows machismo, but in terms of sensitivity, in terms of sorrow, they are never allowed to cry, for this is a feminized act, one that is disallowed for men.

My practice is very simple in terms of what I actually do—drink a bottle of tequila and have a friend hold me, for example—but within the simplicity of the gesture, it is very complicated. Everyone has a family member who has a drug or alcohol problem and can identify with this act of drinking followed by sorrow. The crux of the work of art is to create dialogue, dialogues that are difficult for people to have because they are about subjects that are forbidden or suppressed, though they are so necessary. I always wanted to make work that was sincere and simple. Art is a gate that can take you to all kinds of places. When I was growing up, I always felt that art was about privilege, about luxury, something very outside my world. But I was also deeply influenced by Felix Gonzalez Torres and this idea of giving things.

WRO: When I started graduate studies, I was avoiding the things that hurt the most. My professor, Emma Amos, said “you need to stop fucking around and be in front of a camera or on stage.” She pointed me to the work of Anna Deavere Smith and instructed me to mine all the dark places in my life. I began to create gestures to look at myself beyond the urban, projected version of me. I started making videos, singing breakup songs to myself. I made a crying video also. Then the issue of cultural identifiers became important. I sang these mainstream American break up songs but was also thinking about how much cultural signage is attached to the width of my nose or the curl of my hair. I became much less interested in exploring male standards of high art than the rawness of human nature. The texts The Maria Paradox, about Latina identity, and Reviving Ophelia, about adolescence, became pivotal to my practice. I’m really interested in why we modify our behavior according to social expectations. What I wanted to be went against so many of the tropes of what was expected of me as a Puerto Rican woman from the Bronx. I found myself having to negotiate between my married life and my art career in a way that I didn’t expect. I realized that all the successful women artists I knew were single. So then endurance and the idea of staying in one place, no matter how difficult, began to make itself into my work. In making those two endurance videos in which I am repeatedly slapped, I wanted to see how much I could stand. I wanted to physically and visually manifest how much shit I was willing to take from men. I knew they were difficult works to make. It was even difficult to get someone to make the video performance with me. Violence against women is such a taboo subject, socially unacceptable but also is not discussed in any real way. My family could not watch the videos.

Ivan, you said that we are bonded by pain. I think it’s very astute to say that, and very honest. As a survivor of domestic violence, I understand that it is about cycles of pain and about the things that people don’t want to talk about, about the fact that women are submissive to men but we don’t want to acknowledge it. We all play our parts in it. My work with the garbage is about this in that it makes visible the emotional baggage that we place on others. This piece was powerful because I was asking people not only to bring me their shit, but to literally dump it on me. This symbolic act reflects a paradigm of human behavior.

RAA: Ivan, has your work ever been censored because of the nature of your exploration of particular themes? How do you explore the issues of censorship around transgendered people in your work?

IM: My work has been censored three times. In 2003, during the DL (Down Low) exhibition at Longwood Art Gallery in the Bronx, the work Untitled/I’m just trying to show you, in which I made out with a guy was censored. From that show, Luna Ortiz’s and my works were censored when the school had functions in the gallery because they were deemed inappropriate. In Queens, I was included in a show with a work titled There but for the grace of God go I, in which I turned a space into an HIV testing center. Just before the show opened, I received an email from the curator saying that the director felt the piece was inappropriate and that they could not exhibit it. Then there was a chain of emails and I was accused of hiding behind social causes and making work that didn’t have content outside of these causes. I think, really, we are talking about AIDS-phobia and how HIV is still stigmatized and how it is misunderstood. And something similar happened at Longwood in the Bronx where a security guard shut down the piece, because she felt that the project was compromising public safety. The language that is used is always about the appropriateness of where AIDS can be discussed. How is an art project inappropriate for a gallery space? Even at El Museo del Barrio, the work was treated as a public program, not an art project. The work forces these aspects to be discussed, it forces communication between people. I like collapsing and exposing those things and that my work forces people to do that.

RAA: Wanda, in the creation of your character, Chuleta, parody and irony both play important roles. I feel that through her character you are able to reveal many hidden truths. Tell us a little about public reactions to Chuleta and about the desire to silence her voice because it didn’t fit a particular view of what is “appropriate.”

WRO: For me, the backlash came when I put the videos on the Internet, in a realm that was unexpected and for which the audience was unprepared, people who were not museum goers and didn’t encounter the works as art. People wrote “dumb bitch” a lot, people wrote “get a fucking education,” I finally had to disable the comments on YouTube. My interest in this dark humor comes from studying comedy in college, and farce and satire, where you can really get close to a sensitive issue by using comedy. The idea is to get really blurry, and the blurrier you make the work, the better. People get really angry and insulting, writing hate mail about this character as though she is real, when she is just a persona that I invented. For me the bigger censorship issue, is the complete omission of this work from conversations about the kind of work I’m making. I’ve been public about the purposeful omission of my work from this discussion because I’m not perceived as “black enough.”

IM: Maybe this is a problem how “Latinoness” works, and how it is too complicated because it is made up of so many nationalisms. And America is basically a black and white country. Latino and Asian are invisible.

RAA: I believe this invisibility has influenced the practices of mainstream cultural institutions and the work of scholars, as Wanda has pointed out. While it is not difficult to name quite a few “artstars” of the contemporary art world from certain racial groups, it is nearly impossible to do the same for Latino artists. Though the area of Latin American art and art history has been developing extensively over the last 40 years, the art history of Latinos in the United States is still being written and this is, in turn, reflected in collecting and exhibition practices, scholarly study and the development of a history of U.S.-based Latino art. This is particularly true of performance.

Rocío Aranda-Alvarado is Curator at El Museo del Barrio where she is working on an exhibition exploring the African presence in contemporary Latino art. She recently organized LA BIENAL 2013, El Museo’s biennial of emerging artists, as well as the permanent collection exhibition for 2013-14. Her curatorial work and research focuses on modern and contemporary art of the Americas. She is the former curator of Jersey City Museum, where she organized significant retrospective exhibitions of the work of Chakaia Booker (2004) and Raphael Montañez Ortiz (2006) and group shows on various themes including Tropicalisms: Subversions of Paradise (2006), The Superfly Effect (2004), and The Feminine Mystique (2007). Ms. Aranda-Alvarado is also on the adjunct faculty of the Art Department at the City College of New York. Her writing has appeared in various publications including catalogue essays for the Museum of Modern Art and the National Gallery, Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Art Nexus, Review, the journal of the Americas Society, NYFA Quarterly, Small Axe, BOMB and American Art.