April 30, 2015

Some Thoughts on Art in Mexico from the 1990s and 2000s[1]

Written by Irmgard Emmelhainz

In the past decade or so, an alliance between the state, corporations, private initiatives and art market was consolidated in Mexican cultural production. The proliferation, internationalization, and attainment of global relevance of Mexican contemporary art, had been tied to the global spread of an aesthetic language grounded on the heritage of conceptual and minimal art from the 1960s and 1970s, to the violent changes and social turmoil brought about by neoliberal politics, and to global socio-economic processes inherent to the new world order, including a social turn and a post-political sensibility. In the past 25 years, borders became extremely porous when it came to cultural exchange. In the 1990s, Mexican art began to be disseminated and is now being produced and exhibited everywhere in the world. This rootlessness is a sign of the “post-conceptual” condition of contemporary art. For Peter Osborne, the “contemporary” implies an emptying-out of the concept of postmodernity as a critical and temporal category and its replacement with a singular, complexly internally differentiated global modernity, which implies the spatialization of historical temporality.[2] In this regard, we could think of contemporary art as a site in which constructed conceptualized narratives from all over the world are confronted simultaneously to deliver an attempt to understand the present, by means of a temporal bracketing and spatial condensing.[3] In other words, contemporary art projects a fictional unity into a variety of ideas about time and space providing an illusory common platform that precisely evidences the lack of global time and space and sharp socio-economic differentiation. A concept that goes hand in hand with “contemporary art” is semiocapitalism (or cultural capitalism), the current stage of capitalism embedded in the liberation and financialization of markets, in which creativity and cognitive work are at the core of the production of surplus value, while digital communication has been fully integrated to our everyday lives. Under this light, we must consider two characteristics in contemporary art: first, the de-differentiation of media or what Rosalind Krauss calls the “post-medium” condition in art, which implies that art as a medium-specific enterprise has disappeared, opening up to mixed-media combinations and to de-skilling in artistic production. As a consequence, artists’ practices tend to be plural and with lack of thematic and formal coherence from one body of work to the next. Second, as Frederic Jameson has pointed out, the museum has been transformed into a popular and mass-cultural space that advertises exhibitions as commercial attractions; the hostility with which modern vanguardist artworks were met has disappeared and art has taken a kind of populist turn. This is also due to a change in the structure of aesthetic perception: art has become a unique event or experience in which we consume an idea configured by the conjunction of elements in the work rather than a sensory presence.[4] Furthermore, the prominence of contemporary art in and from Mexico is linked to notions of betterment and development, culture being seen as a tool to achieve them, and to the institutionalization and marketization of the rupture model. In other words, in the past 25 years, a different way of making, exhibiting and circulating art in Mexico joined the globalized economy with the aid of private and public funds. Taking these points into account, it could be argued that art in Mexico of the 1990s and 2000s encompasses a transition from a reflection on the broken promises of modernity from a peripheral point of view and a challenge to the shallow image of Mexicanidad and its institutionalization, to what is termed the “contemporary.”

To begin a consideration of recent Mexican art, after a new historical period was inaugurated in 1989 by the demise of the Soviet Union, we could consider Un banquete en Tetlapayac (2000), a film by Olivier Debroise which debatably sums up the concerns and sensibilities of the Mexican art scene in the 1990s. The film takes up as a starting point Sergei Eisenstein’s séjour at the Tetlapayac hacienda during an unexpected delay in the filming of ¡Qué viva México! in 1931. Eisenstein’s film was key in the elaboration of Mexicanidad or Mexican cultural identity in the 20th Century, based on the filmmaker’s references to imagery by David Alfaro Siqueiros, Jean Charlot, José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera and José Guadalupe Posada as well as to Mexican folklore. Oliver Debroise’s film is an experimental reenactment of Eisenstein’s Tetlapayac episode, when his team spent days drinking, eating and debating at the hacienda. Debroise asked local and international artists, intellectuals, critics and curators (Laureana Toledo, Javier de la Garza, Roberto Turnbull, Thierry Jeannot, Cuauhtémoc Medina, Silvia Gruner, Dmitri Leninovich, Lutz Becker, Melanie Smith, Sarah Minter, James Oles, Enrique Ortiga, Andrea Fraser, Serge Gilbaut, Sally Stein, etc.) to play the parts of their modern analogues, and discuss modernity, politics, the construction of Mexicanidad, Eisenstein’s work, the demise of communism, aesthetics and history. The discussions are tied to the central questions that informed art of the 1990s, including: what would an aesthetic-political project look like in face of the demise of socialism as a container for progressive politics – with Cuba as a very close example – the 1980s 1990s witnessed influx of an array of Cuban artists and intellectuals –, the Zapatista insurrection, the ratification of NAFTA and the liberalization of markets? Parallel to these concerns, a search for alternatives to state sponsorship in order to avoid the instrumentalization of culture took place, resulting in the emergence of fertile alternative exhibitions and spaces for dialogue led by a network of artists and critics (Salón des Aztecas, La Panadería, Curare, La Quiñonera, Temístocles 44, Torre de los vientos, ZONA, Art Deposit, CANAIA), in which explorations of new post-national, post-communist, neo-conceptual sensibilities flourished.

These explorations were led by multitasking cultural producers and by radically experimental curators such as Guillermo Santamarina, who directed the Ex-Teresa Arte Actual and El Eco Musems or Pip Day, who bred an entire generation of young intrepid curators through her workshop Teratoma. In the face of the changes brought about by neoliberal policies, modern “nationhood” narratives became inadequate and irrelevant, and Mexico began to be bereaved of cultural specificity. Market freedom came hand in hand with the liberalization of identity, historical constructions, and a postmodern pastiche-like mestizo hybridity – which were nonetheless explored in Rubén Ortiz Torres’ pieces embodying “cultural misunderstandings”, or Silvia Gruner’s video Don’t Fuck with the Past, You Might Get Pregnant (1995), in which the artist approaches memory through corporal contact, dislocating historical constructs by establishing an eschatological, erotic relationship to it.[5]

Bearing in mind that modern art and the modern world had been tied to industrial capitalism, disciplinary societies, a vanguardist sensibility (perceived as an exhausted strategy), revolution and a communist alternative (both conceived as obsolete), protectionist states including State sponsorship of the arts (in the process of dismantlement), the massification of culture, the ideologies of progress and universality, etc., it could be said that art in Mexico in the 1990s sought to come to terms with this modernity, whose realization in the Third World came to be thought of as extremely limited, for many even failed. This led to a vein in art production that delved into the precarious conditions of working from the fringes of modernity with cheap materials, simple poetic gestures and ephemeral works. Instances that come to mind here are, Damián Ortega’s sculpture Building Module with Tortillas II (1998), Gabriel Orozco’s photograph Sand on Table (1992-93), Francis Alÿs’ performance Sometimes Making Something Leads to Nothing (1998), or Silvia Gruner’s photograph Reparar (1999), all imbued with conceptual, situationist or formal concerns. What also comes to mind here is Pedro Reyes’ reinterpretation of modern architecture, or rather, his revitalization of functionalism translated into the new forms of collectivity brought about precisely though a revision of modernity’s social, political and architectural premises, in Sombrero colectivo (2004), Cápulas (2002) or Zikzak (2003).[6]

Examples of the aesthetic sensibility of the times, are also those that explored the peripheral conditions of their own making by addressing the implications of lack of direct access to canonical works of art from North America and Europe from the 1960s and 1970s – which would be unthinkable today, due to digital technologies and the global profusion of platforms for the dissemination of globalized art, theory, criticism and history. This circumstance, inspired reenactments or remakes that were not parodies, but rather efforts to come to terms with the center by means of copies in order to neatly mark difference and distance[7]. Portable Broken Obelisk (For Outdoor Markets) (1991-1993) by Eduardo Abaroa after Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk (1967) outside the Rothko Chapel in Houston, and Daniel Guzmán and Luis Felipe Ortega’s video-performances Remake (1994-2003), for which they remade key performances from the history of art by artists like Bruce Nauman or Paul McCarthy based on images from art history books, are emblematic in this regard. There are also works that denoted their own “peripheralness” or the “thirdworldness” of Mexico, for example, Yoshua Okón’s video series Oríllese a la orilla [Side to the Side] (1999-2000), in which the artist paid policemen money to let him make videos of them doing various actions (dancing, telling jokes, waving a nightstick/grabbing his crotch). The videos raise a not unproblematic cynical tension between race, class and power abuse (to the policemen by white male privilege), and the fickleness of authority figures as a cultural trait denoting cultural backwardness, yet a sign of the absence of a social contract in Mexico. Another example is the work by SEMEFO, the collective to which Teresa Margolles was a founding member, which worked with materials obtained with or without permission from morgues. Through a coveted catholic, eschatological logic of sacralization of the traces of human remains by transforming them into relics/art, SEMEFO’s work alluded to the impunity, administrative corruption and indolence prevailing in law reinforcement in Mexico, as well as to the socio-cultural implications of bodies, especially of those who died violent deaths.[8]

A group of artists working in the early 1990s associated with the Taller de los viernes [Friday’s Workshop], responded to the debates on Mexicanismo and official art in radically experimental ways. The group included Gabriel Orozco, Dr. Lakra, Damián Ortega, Abraham Cruzvillegas and Gabriel Kuri, who met once a week for nearly five years to discuss common concerns and to experiment and exchange ideas. Seeking exhibition alternatives, they became prototypes for a new, anti-institution, globalized practice: Gabriel Orozco’s Shoe Box at the Venice Biennale in 1993 had defied the very notion of “peripheral artist.” In 1999, they exhibited their work through the Kurimanzutto Gallery (among other international artists) at the Medellín market in the Roma neighborhood, embedded in fruits and vegetable stands. The show was titled “Market Economics,” pointing at a new paradigm of taste marked by the artists’ explorations and experiments and positing a new figure of a global artist who lives off his or her work. Although the work of the members of the Taller de los viernes is extremely diverse, they share some formal and conceptual concerns such as construction, assemblage, the materiality of organic and industrially produced or found objects and more classic formal sculptural concerns (equilibrium, form, spatial relations), and the fact that their works sometimes result in visual puns or political commentary.

All together, narratives about the broken promises of modernity along with the experience of political uncertainty and the turmoil of globalization, gave leeway to small gestures or détournements of the everyday through an array of media. Artists explored the workings of Mexico City’s underground economy and forms of labor, the precariousness of urban working class, their building materials and simple solutions, the qualities of popular craftsmanship, etc., which could be interpreted as statements about the social and political situation materialized in the dislocation of objects from one context to another. These alterations of reality had a critical purport, politicizing urban, social, linguistic, visual and phenomenological space. We could talk about a spatialization in art, which includes a questioning of everyday practices, the imagination of possible spatial worlds, material manifestations of the social or the collective imaginary and a performative actualization of different spatial orders and regimes in a historicizing actual temporality. In this regard, spatialization also implies a struggle over the meaning of places and destabilization of cultural values and social meanings, which were woven into subjective yet transient points of view. Perhaps these two verses from Mónica de la Torre’s poem Crush sum up the subjectivization of space characteristic of what I call spatialization in art:

A point of interest is a chamber of echoes

A place is a container of places[9]

And:

What’s inside if it’s all exterior. Ever notice how the private

never crushes the public? But how it distorts it.[10]

It could be said that spatialization in art went hand in hand with the dismantling of modern, universalist ideologies: the spatiality of the city, or rather a sense of site began to gain relevance, a site that was indeterminate, dislocated and experienced subjectively. The city’s potential as epistemic space and thus a rich carrier of sensible knowledge was exploited, and the capital city of Mexico D.F. became key in the imaginary of contemporary art, a metaphor or allegory of the shifting geopolitical borders, with urban structures seen from subjective points of view and ephemeral eloquent gestures drawing imaginary or transient social and historical realities. Examples of artworks in this vein are, Gabriel Orozco’s photograph Island within an Island (1993) or his documented action Until I Find Another Yellow Schwalbe (1995) (although neither work was made in Mexico City), Silvia Gruner’s video installation Atravesar las grandes aguas ¡Ventura! (1999), Santiago Sierra’s performance Obstruction of a Freeway with a Truck’s Trailer (1998), Melanie Smith’s films, Spiral City (2002), Tianguis II (2003) or Parres Trilogy (2004) or even Pablo Vargas Lugo’s installation-sculpture Visión antiderrapante (2002). There is also Thomas Glassford’s intervention with lights at Tlatelolco University Cultural Center, Xipe-Totec (2010).

Due to its prominence in art, Mexico City underwent a brief moment of exoticization in 2002, when two international exhibitions took place: Zebra Crossing curated by Magalí Arriola (Berlin) and Mexico City: An Exhibition about the Exchange Rates of Bodies and Values (New York and Berlin) curated by Klaus Biesenbach, which posited life in the city as a sensationalist metaphor illustrating the consequences of market liberalization: violence, chaos, insecurity, a deepening of inequality. In these two exhibitions, however, Mexican art got confused with Mexico, and as Daniel Montero put it: none of these two shows was able to escape the enunciation from center to periphery, imposing this narrative in the works[11]. Later on, Mexico ceased to be peripheral and instead, came to occupy the lead not only as a laboratory for understanding the socio-political outcomes of neoliberalization, but of aesthetic and literary vanguard. Amongst efforts to promote international relations to attract foreign investment, Mexico had implemented a policy in the 1990s to fund the education of a new class of cognitive workers who became versatile in the lingua franca of global art, design and architecture and who furnished the new enclaves of sophistication and wealth throughout the country. While it is one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, Mexico is one of the best places for cultural producers. Under Mexican ex-president Carlos Salinas de Gortari, CONACULTA and FONCA were established in 1992 to finance cultural projects, and thus the state became a direct sponsor of culture (in increasing partnership with the corporate sector, especially since 2000) crafting an upper middle class of cultural producers allowing intellectuals, writers, artists, architects, scholars, etc. to live comfortably and to share their work all over the world.

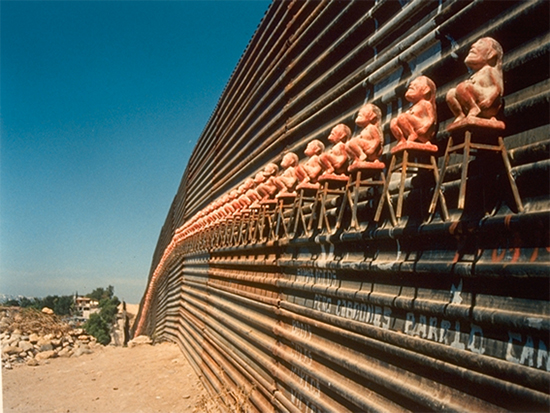

By the beginning of the 2000s, the global arts scene had exploded when nomadism and “post-studio” practices became a condition for aesthetic production. Francis Alÿs’ Turista (1994) and Gringo (2004) or Gabriel Orozco’s Turista maluco (1991) illustrate this. Moreover, the forms of knowledge that can be derived from interventions in spatial givens with critical or political potential were the premise for InSite, a binational exhibition initiative that took place at the border between Tijuana and San Diego, which had five editions that took place between 1992 and 2005. The border became a fertile site for exploring the changes and challenges brought about by the neoliberal economy of sweatshop work and displaced bodies, the new hybridization in popular culture brought about by the flood of foreign immaterial and material merchandise, imaginaries[12] and identities. InSite posited the city as a laboratory to trace the complexity of global shifts through subtle reconfigurations or interventions in urban space or social structures, conceiving the border zone as a combative, troubled and politicized site, the allegory of global power relations and the cradle for global politics. Emblematic works produced under this frame are: Silvia Gruner’s installation The Middle of the Road (1994) and video Narrow Slot/Sueño Paradójico (2001), Javier Téllez’s performance One Flew Over the Void (2005), Marco Erre’s Trojan Horse (1997), Gustavo Artigas’ performance The Rules of the Game (2000), Judy Werthein’s Brinco, 2005 or Krystoff Wodiczko’s Tijuana Projection, 2001. Debatably, a model of aesthetic intervention in public spaces was disseminated by InSite and establishing a platform for other biennials in cities across the world. The platform consisted in inviting artists from elsewhere to do site-specific interventions, thus playing a key role in the transmigration of contemporary art. As soon as the dark outcome of globalization came into light (massive displacement and inequality, war and violence, hunger, financial crisis, environmental devastation), this model reached its limit. Because this model implies having artists foreign to local situations intervene to implement more or less emancipatory or symbolic apparatae in conflict zones, the interventions had begun to appear more and more like palliatives or evanescent solutions to the devastation brought about by neoliberal globalization. The limitations of this proto-political model of intervention are cynically exposed in Renzo Martens’ film Enjoy Poverty III (2006) and in his project to bring cognitive work to Congo, The Institute of Human Activities (2012-ongoing)[13] and articulated by writer Leslie Jamison, when she describes the ethical implications of being a foreigner walking around Tijuana in 2010 at the peak of the violence:

I think maybe if I walk the streets where someone was afraid, where an entire city was afraid, I’ll maybe understand the fear a little better. This is the grand fiction of tourism, that bringing our bodies somewhere draws that place close to us, or we to it. It’s a quick fix of empathy. We take it like a shot of tequila, or a bump of coke from the key to a stranger’s home. We want the inebriation of presence to dissolve the fact of difference. Sometimes the city fucks on the first date, and sometimes it doesn’t. But always, always, we wake up in the morning and we find we didn’t know it at all.[14]

By the 1990s, the colonial distinction between center and periphery had become irrelevant: cultural production and capital began to celebrate decentralization, rendering the distinction between first and third worlds obsolete, at a moment in which the Other had been rendered transparent by art, ethnography and journalism. The globalized market, with its ability to go beyond national divisions integrated first and third worlds, forcing certain areas of the third world to “develop,” creating pockets of wealth and cultural sophistication within the third world, and areas of destitution and misery within the first. The demise of communism in 1989 and the discourses on development brought about by globalization, made the “Third World” disappear as an aesthetic-political category, which was substituted by a temporally equivalent yet being “elsewhere” (from our here). The border (or other formerly peripheral cities and areas) are the “elsewhere,” which is always a site of urgent intervention and imminent danger, epistemically and symbolically rich, and yet seldom a site of contestation, where the underclass, the excluded from global processes survive in precarious conditions (favelas or misery belts, zones disconnected from the economy, neglected by States, war zones before “pacification”, etc.). In this context, Francis Alÿs’ Reel Unreel (2012) filmed and shown in Kabul in a cinema in ruins, is a sign that contemporary art in Kabul (as a branch of Documenta 13 in 2012), arrived before the fire stopped and transnational subcontractors and corporations came to reconstruct, evidencing how art has become a palliative tool as well as harbinger and inseparable companion to neoliberal socio-economic processes.

Alternatives to the homogenizing cartography drawn by Empire – the decentered and deterritorializing apparatus of rule that has progressively incorporated the entire global realm within its open, expanding frontiers[15] – were sought by instances such as “Conceptualisms of the South Network,” a plural platform for cultural mediators for challenging and proposing more equitable forms of producing and sharing knowledge at a transnational scale, under the premise that “Southern” knowledge processes come from subordinate places, bodies and aesthetics that can challenge Empire[16]. Another effort to draw an alternative cartography to Empire is Pablo Helguera’s School of Panamerican Unrest, a public art project initiated in 2003, which alludes to the Panamerican ideals of the 19th Century of American integration, through a voyage by car, from Anchorage to Tierra del Fuego in 2006. At each stop and in a wide array of venues, a portable school was set up to discuss and to house performances around Panamericanism.

Half into the first decade of the 2000s, discourses about globalization had advocated the overcoming of geographic divisions, linguistic barriers and ethnic differences, undermining the modernist concepts of Nation and the modernist ideals of ethnical and formal purity. Within this discourse, “Mexico” became instead of a geographical area, a concept defined outside of its own territory by means of global economic exchanges (immigrants, cultural capital abroad, exported goods like culture). Paradoxically, the all-encompassing power of globalization caused the proliferous homogenization of some aspects of modernism: to English and conceptual art as the lingua franca of cultural exchange, can be added suburban or alternative urban lifestyles, generic consumable ethnic identities, and other lifestyle and cultural traits disseminated by the global mass media (Starbucks, Apple computers), democracy, neo-modernist architecture or even the discourse of human rights. In this regard, Miguel Ventura’s work from the 1990s set up a critique of the globalization of Western modernism, specifically, the utopian aspects of fascism, capitalism, psychoanalysis and abstraction, their spreading throughout the world, and their colonializing effects in the face of market liberalization. Through a fictitious institution, the “New Interterritorial Language Committee” (NILC), Ventura set up an ideological project with proto-fascist traits and a system of inversions thematizing the production of new subjects enabled and encouraged to contain and to produce their own “universal” language as a cure from alienation and colonial feelings of inferiority. NILC is a parody of society’s primal sources of repression (language and educational institutions, as well as cultural spaces and social rituals) that uncannily mirrors some of the aspects of globalized Western modernity normalized in our lives. His video, How Can I Love You, My New Little One? (2000), part of his 2001 Carrillo Gil Museum exhibition, “The PMS Dilemma,” depicts a NILC transformation ritual that enables a subject to become the producer of “his own private language.” This echoes Frederic Jameson’s assertion that modern fragmentation had begun to splinter society as private languages came to be developed by each (ethnic, economic) group to the point that each individual became a kind of linguistic island.[17] Accordingly, Ventura’s “PMS Dilemma” is a critique of the normalization of Western modernism and English as the linguae francae of globalization, expressed through the incessant creation of private languages and idiosyncratic self-expressions through a homogenization of the codes of modernity and the fragmentation of national, communitarian and familial ties.

Working from the diaspora in California, Guillermo Gómez-Peña’s work in the 1980s and 1990s was aligned with identity politics and aesthetics in the US. Later on, Gómez-Peña’s performative works began to question the inequalities of the current global order and to celebrate: immigration, nomadism, hybridized identities and practices, to transmit urgency for new strategies for political dissent, to denounce xenophobia, precarious labor conditions and to invent strategies to revitalize community ties, through new technologies, virtual reality and cybernetics, to elucidate the withering of national consciousness, etc. In his video-performance reciting a poem, Declaration of Poetic Disobedience (2005), and despite its liberal disclaimer condemning terrorism, Gómez-Peña carves out a discursive position to contest and resist the homogenizing and devastating power of globalization by reconfiguring the notions of “us” and “them,” highlighting how cultural differences and contestatory positions from subalterns had become commodities.

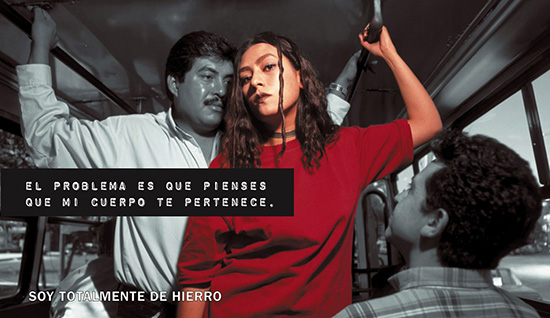

Taking up visual culture as a site for politicization along the lines of feminist video and performance artists in the 1970s, the work of three women: Ximena Cuevas, Lorena Wolffer and Minerva Cuevas has a common concern in elucidating how the media and corporate marketing construct imaginaries that become entrenched in cultural assumptions and how they can be contested or overturned. For example, Ximena Cuevas’ videos can be described as visual culture satires filtered through personal idiosyncrasies, distancing the viewer from the melodramatic spirit of Mexican culture. For her part, Lorena Wolffer’s work operates at the intersection of art and activism addressing the cultural fabrication of gender, and has included pedagogical platforms for collective development to counter gender violence and to give women their voice. Her iconic series Soy totalmente de hierro [I am Totally Steel], consists of 10 billboards scattered throughout the city in 2000, parodying a department store’s marketing campaign that capitalizes stereotypes about white upper-class women consuming and posing, posited as the female ideal. Minerva Cuevas founded in 2000 Mejor Vida Corp. [Better Life. Corp] a multimedia project embodied in a corporation geared at identifying and solving poor residents of Mexico City. There is also Daniela Rossell’s series Ricas y Famosas [Rich and Famous] of almost 100 photographs depicting women members of the Mexican oligarchy. Rossell’s photographs can be described as ethnographic studies of the ruling class’s decadent fantasies embodied in the women’s poses and their home interiors. The images express a contradiction between the home as a “private” space vs. the “public” concerns of the (gender and class) politics at stake. By providing her subjects the opportunity to construct their own visual images/subjectivities, the women enact fantasies of self-objectification and sexualization, merging with the kitsch yet luxurious décor of their homes, painstakingly maintained by the servants who sometimes appear in the images.

Rossell was associated, along with artists like Miguel Calderón, Yoshua Okón, Carlos Amorales, Artemio, Pablo Helguera, Minerva Cuevas, Claudia Fernández, Gustavo Artigas, Daniel Guzmán, Richard Moszka, Luis Felipe Ortega, Sofía Tabóas, Diego Toledo, Jonathan Hernández, Pedro Reyes and Vicente Razo to the “Generation XX”. They showed at La Panadería (founded in 1994 by Calderón and Okón),[18] and Pablo Helguera characterized their work as a hybrid between Mexican modernity and global pop and art historical references.[19] For instance, Miguel Calderón used the camera to create a one-step removed subjectivism, manipulating his own image as a front for the unstable contemporary Mexican cultural/social and political identity. Debatably, Calderón shared with Okón and Amorales a cynical stance toward the fatal outcome of globalization, which early on in Mexico, came to be synonymous with the sweatshop economy and thus with the denigration of laborer’s living and working conditions. There is, for example, Calderón’s 1998 series of photographs in which workers (janitors, guards) from the MUNAL (National Museum) pose emulating paintings from the museum, evidencing the working class’ estrangement from “high culture” obliquely addressing race issues. In Carlos Amorales’ Flames Maquiladora (2001-02), viewers were invited to cut cherry red vinyl to manufacture Mexican luchadores [wrestling] boots, which were sold afterward as art objects (the installation included ads with the following advertisement: “Work for fun! Work for me!”). For All Employees (2002), Yoshua Okón visited Carl’s Jr.’s restaurants in LA with the purpose of filming short videos in which each of the employees introduces him/herself behind the counter as if to a customer. Then, Okón spliced all the videos together transforming image and sound into an abstract mass projected behind a real counter at a real scale. What these works have in common is that they underscore the relevance of new or older forms labor in sustaining the global economy while making invisible the conditions of labor under neoliberalism. In the same cynical vein, the work of Santiago Sierra simultaneously underscores and invisibilizes labor by juxtaposing bodies that are worn out more than other bodies, which have been uprooted or dispossessed with more privileged bodies in “confrontations” in museums, galleries or biennials (Workers Who Cannot be Paid, Remunerated to Remain Inside Cardboard Boxes, 2000 or Wall Enclosing a Space, 2003). In Sierra’s work, paid labor is exploited at three levels: by the machinery that wears out their vitality, as it is put at the service of the artist’s own cynicism and for the aesthetic enjoyment of the privileged class. The cynicism and ambivalence that characterizes this vein of work could be ascribed to the “post-communist condition,” in which a formalization of revolutionary disillusionment is brought about by the demise of the Modernist communist utopia. According to this narrative underlying vanguardist art, workers would be emancipated from the tyranny of work and the bourgeoisie; this possible future however, was truncated by the fact that communism took place as an event in actual history failing as ideology as well as in practice. With contemporary cynical art, in turn, the alienation purported by consumer society does not appear to be something problematic and neither does the deepening of inequality and unemployment, as the proliferation of vulnerable subjects becomes normalized. Another sensibility that we could describe as “post-communist,” is present in work based in futile, grand gestures that lead to nothing. Silvia Gruner’s 500 of Impotence or Possibility (1995) and Away from You (2001) are based on Sisyphean tasks condemned to eternally repeat themselves – dipping with a crane a 500 Kg necklace at the San Diego Bay and swimming in one direction in a loop – leading only to frustration. There are also Enrique Ježik’s powerless aggressions such as A Kilometer (2004) or Untitled (Damage and Reparation) (2005), which involve heavy machinery, and Francis Alÿs’ ambivalent Paradoxes of Praxis: a series of poetic actions in which the artist performs seemingly futile tasks or labors which may or not become commentaries on the socio-political situation. For the most recent one, Paradox # 5: Sometimes We Dream as We Live, and Sometimes We Live as We Dream (2014), Alÿs kicks a ball of fire in the destroyed urban and social tissue of Ciudad Juárez. These works operate in a perpetual present evoking a waiting stance to which nothing will ever follow.

Artists like Edgar Orlaineta and Carla Herrera-Pratts, associated with Art Deposit, the space founded in 1996 by Steffan Bruggeman, Iñaqui Bonillas and Ulises Mora, reinterpret modern, conceptual and minimal art strategies to address socio-political concerns (Carla Herrera-Pratts’s Remesas-Sending Money Back, 2003-), personal preoccupations (Iñaqui Bonillas, J.R. Plaza Archive, 2003) or to produce institutionally-critical conceptual statements, as in Bruggeman’s work (Naked Girl, 2003 or Show Titles, 2000-). There are also Diego Teo’s translations of the readymade to visual metaphors and spatial markers (Untitled, 2003), Antonio Vega Macotela’s or Claudia Fernández’s transposition of site-specificity to community-based work (Time Exchange, 2006-2010), Julieta Aranda’s exploration of the components of capitalism: politics, territory, time and exchange the components of capitalism through conceptual strategies (You Had No Ninth of May, 2008), or Mariana Castillo-Deball’s archaeological research on the role objects have in how we understand history, and how they can deliver new connections and meanings (Stelae Storage, 2013). Some artists belonging to this generation reworked the 1990s concern with public space and the spatialization of art by blurring the interior or exterior quality of the publicness inherent to artistic production. In other words, art came to reflect upon sites located temporally, highlighting how their status as public or private was no longer relevant in the face of the rampant privatization of everything. For instance, Héctor Zamora’s intervention on the façade of the Carrillo Gil Museum, Paracaidista, Av. Revolución 1608 Bis (2004), for which the artist erected a precarious housing unit with self-construction techniques popularly used in building shanty-towns. The ambivalent status of the private or public character of the space was made explicit by the artist taking up residence for three months in the space, pointing also at the incipient privatization of funding for the arts.[20] Marcela Armas’ Un día de trabajo [A Day of Work], 2007, is a performance in which the artist asked ten medical assistants at the IMSS [The Mexican Institute for Social Health] to perform their daily tasks by wearing an enormous uniform that kept all of them bound together. In the performance, private interest, collective desires and the need to negotiate all of them for the sake of efficiency come into tension, connecting societal exteriority with the inside of the bureaucratic workings of the institution. Moreover, Diego Berruecos’ visual investigative archive, La solución somos todos [We are All the Solution] (2011) delves into the visual history of the PRI [Institutional Revolution Party], evoking the politics inherent to the language, landscape, collective memory and PRIísta architecture, interrogating how these sensible manifestations have become part of Mexican culture. Their material and sensible omnipresence are the grounds for taste and an ideological unconscious sensibility.

![Marcela Armas, Un día de trabajo [A Day of Work] (2007). Performance documentation. Courtesy of the artist Marcela Armas, Un día de trabajo [A Day of Work] (2007). Performance documentation. Courtesy of the artist](/images/stories/no10/marcela armas un da de trabajo art and politics.jpg)

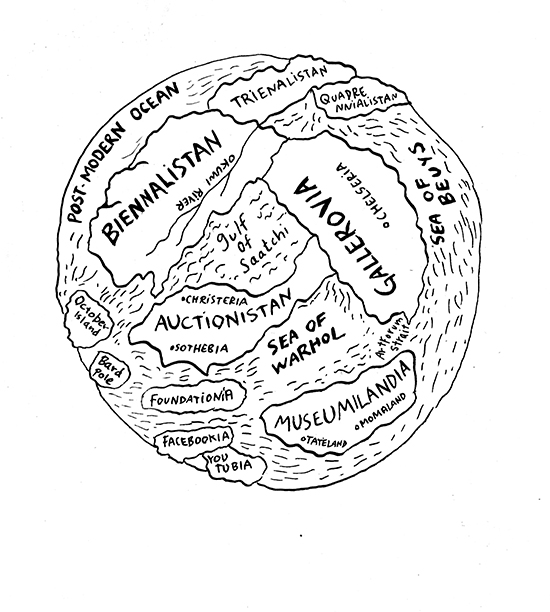

Within the vein of institutional critique, the museum became the medium of the work of art, submitted to the modernist tradition of reflexivity. For instance, Pablo Helguera posited the institution of art (comprised of social relations, discourses, a physical space framework) as a means and as a theme in his work in the 2002 symposium he organized The Museum as Medium, which examined the legacy of institutional critique, in his book Contemporary Art Style Manual (2007), the Artoons, 2 volumes of artworld cartoons (2009) or his advice blog The Estheticist (2010-11). Mario García Torres’s work also comes to mind, based on hidden stories or rumors from the history of art or film, which he translates to videos, books, exhibitions, vitrines or postcards.

Analyzing art historical lineage and paternity, García Torres has revisited artists like Robert Barry, Alighiero Boetti, or Dr. Atl, to investigate the mechanisms that make possible that their works become art, exploring the system that supports their narratives. There has been further institutional critique work by Adriana Lara Art Film I: Ever Present, Yet Ignored (2006) and Banana Peel (2008), by the collective Tercerunquinto, and Débora Delmar. These instances of institutional critique seem conservative when compared to Miguel Ventura’s Cantos cívicos 2008-2009, a Gestammt-installation that inaugurated MUAC, or the National University’s Museum of Contemporary Art. Ventura’s kamikaze-vanguardist exhibition drew an analogy between 1929 and 2008 as years that mark both the beginning of the financial crisis as well as an era of racism and xenophobia. Inside an enormous structure parodying contemporary museum starchitecture, Ventura staged NILC’s transformation into a fascist regime. The structure included a collection of Nazi paraphernalia, a vivarium for rats, tunnels and a gigantic collage that included swastikas interlaced with dollar signs, portraits of U.S. soldiers fallen in the war of Iraq, heterosexual and gay porn, images of fecal matter, a collection of ethnic dolls hung hierarchically (white on top, brown and black at the bottom), all presided by Milton Friedman being fed shit flowing from a silver spoon. Ventura’s installation drew an analogy between 1930s Nazism as a sensible, cultural and social apparatus that existed to legitimate the extermination of its racial and ideological Other, and contemporary art’s ties to the global neoliberal oligarchy as their means to legitimize and/or obscure the ongoing processes of dispossession, environmental destruction, extermination and deepening of inequality.

The constant transmigration of artists across the globe with Mexico City as epicenter, attests to the fact that Mexico has been consolidated as a crucial field for the production and circulation of global contemporary art. The field has expanded its operations transcending the divisions between institutional and alternative spaces, private and public, as new spaces and agents keep on emerging in the context of a blooming art market, exhibition, production and education spaces. This has been achieved through a mix of State and corporate funding and specific policies to support and export cultural production. For instance, the State’s collaboration with the art market investing in the Zona MACO art fair – not only buying but also covering travel for international museum directors, curators and gallerists – and in general implementing an official program to guide the symbolic development to satisfy the demand for cultural, creative assets and the appetite for luxury goods.[21]

The search for alternative exhibition and dialogue spaces which was a concern in the 1990s, had become by the mid 2000s legitimation work, achieved through rupture or contestation of discourses and practices, through marketing strategies, and by weaving networks with certain discourses within the institution of art and by creating alternative spaces or practices. An example is the major exhibition that took place in 2007, The Age of Discrepancy: Art and Visual Culture in Mexico, 1968-1997 at the MUCA UNAM (the Museum of Science and Art at Mexico’s National Autonomous University). From the point of view of academic and historical legitimation, the exhibition sought to build a narrative of the plastic of modern Mexico, positing a genealogy of contemporary art in which the modernist utopia is translated to a modernity that enters a crisis with the demands and repression of the student movement in 1968. In this narrative, 1968 inaugurates an era in the Mexican arts in which artists affirm their right to disagree with the canon dictated by institutions, the market and conventional taste promoted by cultural industries. The exhibition posited “discrepancy” as a healthy and non-violent option to authoritarianism and art as the proper field in which societies can analyze, question and correct itself to undo “authoritarian temptations.” In this narrative, the crisis of Modernity was followed by mourning the failure of modernization in Mexico in the 1990s preceding a new neoliberal “democratic” era, in which cultural institutions are consolidated as containers of dissidence bestowing to art (of increasing corporate sensibility) a function of disagreement, revelation, shock or normalizing cynicism. In that regard, the UNAM became the sentinel of the heritage of contemporary art – especially as the host of the University’s Contemporary Art Museum (or MUAC), inaugurated in 2008 holding a collection of dissident art since 1968. The University has therefore become the last standing bastion of the rapidly waning education system in Mexico and the official container of (middle class, but not indigenous) symbolic discontent sponsored by corporate interests. The increasing corporatization of art, through sponsorship of symposia, projects, exhibitions, grants, publications and the presence of board members in public museums representing corporate power and interests, has given leeway to the slow transfer of cultural capital to the corporate sector. Furthermore, in the past 10-15 years, an emerging creative class has been giving life to certain areas in the Mexico City where galleries, gourmet bakeries, boutique hotels, design shops, architecture offices, visual artists’ studios, etc. have proliferated. Highlighting the ties between the real estate economy and the art market, this cultural transformation has been also marked by two philanthropists who have erected museums in an old car manufacturing area in Mexico City known as Nuevo Polanco, populated by skyscrapers lodging transnational corporate headquarters, luxury housing and offices. The Soumaya Museum’s populist philanthropy is reflected in the mediocre quality of its universalizing art collection, while the Jumex Museum embodies corporate high culture with a holding of international contemporary art, from Minimalism to young global art. Both museums reflect company interests – the recent cancellation of the Hermann Nitsch show at the Jumex Museum attests to this –,[22] as well as their owner’s tastes, and serve as public relations and marketing instruments while they seek to contribute to the country’s “human capital.”

In this panorama, it seems difficult to think about a horizon of critical autonomy. Art in particular and culture in general are not adjacent to the State, corporations and media but are the central machinery for the administration of consensus and the channeling of antagonism. Moreover, the Mexican context is imbricated in global processes and is thus losing its logic of specificity; as a consequence, we are facing problems and challenges that are analogous in other countries that are not necessarily in the South. What distinguishes contemporary from modern art is that nowadays, art and culture are at the thick of neoliberal processes: not only culture in general and contemporary art in particular are power’s arms, but States and corporations are investing in them because they conceive them as sources of surplus value, economic growth and palliatives to the ravages caused by neoliberal policies in the social tissue. The real problem here has to do with the fact that art no longer designates a reproductive or representative realm but a field of social and economic production and power. Art’s autonomy has therefore become a problem not because it legitimates anything as art or anyone as an artist but because it is a realm for the production of surplus value. Moreover, the Artworld is part of an economy of specialization and production of social relationships that materializes in exhibitions, conferences, residences, vernissages, homages, VIP parties and presentations. The links and the network created are more important than the works or projects themselves, therefore, the Artworld is a context and a social network of distribution. At the same time, contemporary art is an amusement park for the 1% with the function of embellishing capitalism. This is why contemporary art is inextricable from precarity, exploitation, dispossession, the war against organized crime and real estate bubbles. If contemporary art’s ambition is to condense artistically the economic processes of globalization in an attempt to understand the present, then it will need to take into account an ideological critique as well as its inextricability from the processes of late capitalist cultural production.

[1] This text is perhaps the beginning of a larger investigation; due to its scope and limitations, it had to be all-encompassing and yet reductive. I would like to thank Jimena Acosta, Tatiana Cuevas, Pip Day, Silvia Gruner, Damián Ortega, and Miguel Ventura for their generous readings and comments of earlier versions of this text.

[2] Ibid., p. 19. Akin to what Nicolas Borriaud termed the “Altermodern” in his Altermodern (London: Tate Publishing, 2009).

[3] Miwon Kwon, “Questionnaire on the Contemporary October 130 (Fall 2009), p. 17.

[4] Frederic Jameson, “The Aesthetics of Singularity” New Left Review 92 (March-April 2015).

[5] Cuauhtémoc Medina, “Irony, Barbary, Sacrilege” (1997) trans. Ellen Camus, available online: http://v1.zonezero.com/magazine/essays/distant/zironia2.html

[6] Tatiana Cuevas, interview with Pedro Reyes, Bomb 94 (Winter 2006), available online: http://bombmagazine.org/article/2779/pedro-reyes

[7] Olivier Debroise, La era de la discrepancia arte y cultura visual en México 1968-1997 (México D.F., MUAC, 2007), p. 406.

[8] Ana Romandía, “Semefo 1990-” Artes e historia de México (Octubre 2011), available online: http://www.arts-history.mx/pieza_mes/index.php?id_pieza=30092011170758

[9] Ibid., p. 28.

[10] Mónica de la Torre, “Crush,” Public Domain (New York: Roof Books, 2008), p. 28.

[11] Daniel Montero, El cubo de Rubik, arte mexicano en los años 90 (México DF: Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo, 2013), p. 217.

[12] As the creative and visual dimension of the social world.

[13] See: http://www.renzomartens.com/news

[14] Leslie Jamison, The Empathy Exams, (New York: Graywolf Press, 2014), p. 59.

[15] Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 2000), p. xii.

[16] Joaquín Barriendos, et al, “Micropolitics of the Archive – Part I: Southern Conceptualisms Network and the Political Possibilities or Microhistories” Field Notes 02, available online: http://www.aaa.org.hk/FieldNotes/Details/1208

[17] Frederic Jameson, “Postmodernism and Consumer Society”, The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture Hal Foster, Ed. (New York: The New Press, 1983) p. 136.

[18] See: Jimena Acosta Romero, “La Panadería, 1994–1996: un fenómeno sociológico, estético y generacional”. Tesis de licenciatura en Historia del Arte, Universidad Iberoamericana, México, D.F., 1999.

[19] Pablo Helguera, “La generación XX y su doble encrucijada” Exit Mexico ed. Rosa Olivares (2005), p. 72.

[20] See: Edgar Alejandro Hernández e Inbal Miller Gurfinkel, eds., Sin Límites: Arte Contemporáneo en la ciudad de México 2000-2010 (México D.F.: Promotora Cubo Blanco A.C., 2013)

[21] See: Blanca González Rosas, “Arte: Zona MACO y los invitados de CONACULTA” Proceso April 19, 2012, available online: http://www.proceso.com.mx/?p=304846 and also: Irmgard Emmelhainz, “Art and the Cultural Turn: Farewell to Committed, Autonomous Art?” e-flux journal #42 (February 2013) available online: http://www.e-flux.com/journal/art-and-the-cultural-turn-farewell-to-committed-autonomous-art/

[22] See Victoria Burnett, “Museo Jumex Cancels a Hermann Nitsch Show” New York Times, February 24, 2015, available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/25/arts/design/museo-jumex-cancels-a-hermann-nitsch-show.html?_r=0