October 22, 2016

The Third World Strikes Back: Neoliberalism and Space Age Relics in the Sculpture of Simón Vega

Written by Seth Roberts

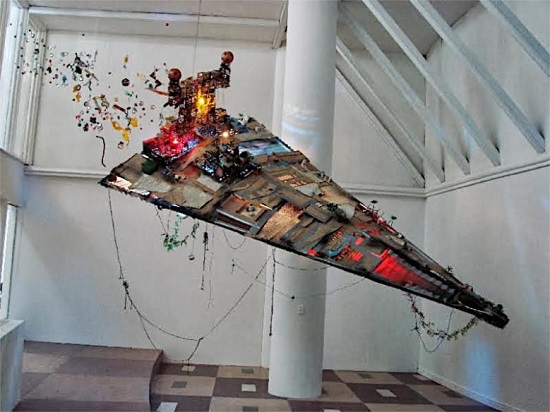

What does it mean to be modern in the Third World? Although tenuously defined at best and inviting a great deal of controversy and disagreement, the label of the Third World is commonly applied to developing nations seen as peripheral or less advanced than their more politically influential counterparts. This issue of modernity is explored in the unique work of the Salvadoran artist Simón Vega, whose drawings and sculptures provide a unique commentary on contemporary Central America as a marginalized and often overlooked cultural space. This essay will serve as an introduction to Vega’s work, specifically the series Tropical Space Proyectos, which consists of a variety of sculptural installations and drawings inspired by the exploration of space. Produced entirely of discarded objects found at the site of each distinctive installation, these space capsules, rockets, and planetary rovers hold a heavy symbolic meaning. At once a criticism of the lack of technological advancement of Central America and a statement on the legacy of the Cold War in the region, Tropical Space Proyectos is a powerful reminder of both the real and symbolic divide of modernity in the contemporary world.

As a Salvadoran whose work has appeared extensively in Europe, the United States, and Latin America, Vega’s artistic production reveals a preoccupation with the cultural and political exchanges between the international world with El Salvador and Central America. Born in San Salvador in 1972 and raised during the height of the Cold War, the position of El Salvador in this international long-term conflict is a primary theme in his sculpture. Vega holds degrees from universities in both Mexico and Madrid and many of his works are assembled from found objects, trash, or waste materials. The use of these discarded supplies adds an ironic element to sculptures which serve as commentaries on the vast cultural differences between Europe, the United States, and Central America and El Salvador. The ephemeral nature of the rocket ships, spying cameras, and recreated art museum buildings reveal a powerful contrast between the technologically advanced original objects and the functionally inoperable recreations of the artist. Yet at the same time there is a humorous, whimsical element to these creations, which express a desire to imitate the high technology of the first world by any means necessary via the use of cheap or readily available supplies.

The idea of modernity or contemporaneity in Central America is a complex topic that entails visions of a violent and unsettled past. With the signing of peace agreements ending years of armed conflict in El Salvador in 1992 and in Guatemala in 1996, the decade of the 1990s initially promised a vibrant future free of the instability and violence of the years of warfare. Yet the end of armed conflicts in these two countries also marked a shift in international attention. The subsequent postwar period has been noted for the continuation of violence in addition to increased rates of violent crime, the rise of drug trafficking and gangs, and weak or ineffective governments. Investigations into the atrocities of the past have proven gravely dangerous: as a retaliation against his defenses of human rights and participation in the investigative report on abuses titled Guatemala: Nunca más (Guatemala: Never Again), the Roman Catholic Bishop Juan José Gerardi was murdered in cold blood in April 1998. Perhaps counter to common wisdom, crime rates have not subsided in the years following the end of warfare. The Salvadoran novelist Horacio Castellanos Moya has described this continuation as a “recycling of violence” due to an ingrained culture of violence in the region, the lack of nonviolent outlets for ex-soldiers and combatants after the ceasefire, and the absence of educational or economic alternatives to violence as a means of survival.

The initial high hopes of peace agreements quickly gave way to a profound pessimism and frustration with the inability to transform these shaken societies. The scholars Carlota MacAllister and Diane M. Nelson have emphasized the short-lived triumphs of the early 1990s and illustrate the painful lack of progress in contemporary Central America:

Attempts to bring to justice the perpetrators of genocide and war crimes have been wearyingly slow and difficult, hampered by official obstructionism, fearmongering, and outright violence. As the tendrils of narcotraffic penetrate ever deeper into state structures and everyday life, the unresolved crimes of the past are compounded by the ever more frequent appearance of new cadavers, now reaching rates comparable to the worst years of the war. Violent evictions of peasants from the land to plant biofuel crops or build mines and dams are increasing, and an army general has returned to power, now through ‘democratic’ elections (Nelson and MacAllister 2013: 7).

In addition to the dynamic social concerns facing the region in the aftermath of war, the implementation of neoliberal policies in the past quarter-century have also had a profound effect on present-day Central America. In its most basic form, these policies have fashioned a deregulated opening of economies to foreign investment and trade through a privatization of public services. In the context of deregulation, fiscal austerity programs, and the vast reduction of social welfare programs and governmental protections, neoliberalism has sparked widespread indignation and rebellions from individuals deprived of traditional rights and benefits. Described as a “race to the bottom” by the scholars Eric Hershberg and Fred Rosen, these programs have prioritized economic security over individual and societal protections:

Since the early 1980s, financial security has replaced social security as a policy goal; social inequality has grown; income has been redistributed upward; and, to lower the costs of doing business, the working poor have deliberately been deprived of economic opportunities an social mobility. (Rosen and Hershberg 2006: 7).

Although Simón Vega is considered a Central American artist who currently resides in El Salvador, his production borrows heavily from American culture. This is not surprising given the long and divisive relationship between the United States and Latin America. Approximate statistics indicate the vast waves of migrations between these two regions in recent years. Roughly 1.5 million Salvadorans currently live and work in the United States and remittances from these immigrants make up over half of all report earnings and more than 17% of the GDP of El Salvador (Gammage). Given that many individuals fled the violence of armed conflict in the 1980s, these patterns of mass migration have continued even after the end of war as the aftereffects provide few economic or educational incentives to remain.

The designs and sculptures of Tropical Space Proyectos reflect the cultural borrowings and international influences of the many Salvadorans who have emigrated abroad or have seen family or friends leave for reasons of safety or personal opportunity. At the same time, the works illustrate a wide spectrum of cultural and social commentaries on modernity in Central America as a marginalized area overlooked during the Cold War space race between the United States and the Soviet Union. As Simón Vega describes the sculptures on his personal webpage,

They portray Central America as a region with dreams of technological progress and modernity that is caught in it's own cultural, social and economic limitations, however, one that is not devoid of humor and creativity. These works speak of Central American history and its relation to World and Space exploration history but on another level, they also speak of [widespread] human isolation [in] today's highly technological societies despite the illusion of social interaction by means of digital technology. (simon-vega.blogspot.com)

Assembled from a collection of discarded items found in the trash such as hoses, plastics, cloths, aluminum cans, and jumbled wires, Third World Sputnik is a curious exhibit to comprehend at first glance. As opposed to the shiny metal exteriors and cutting-edge technology of the space capsules of the 1960s, this unsettling recreation of the famous Soviet craft seems more like a parody than a vessel designed to reach orbit. When viewed together, the seemingly random found items forming the design of the capsule create a curious hodgepodge of colors and spaces that resembles in form but not function the original Soviet craft.

The interior of the Third World Sputnik is blunt reminder of the differences between the technological advancements of the First and Third Worlds. While one imagines the actual Sputnik cockpit as a complicated array of flashing lights, controls, and navigational or scientific equipment, the inside of Vega’s creation is a humbling reminder of the technological limitations of contemporary Central America. Instead of a view screen or computer, the ostensible pilot of this contraption must fly the ship using only a motley arrangement of cooking pans, buttons, plastic toy cars, and an antiquated television set. A brightly colored water gun and a roll of toilet paper hanging from a wall made of cheap blankets and cloth round out this improvised cockpit.

This exhibit reminds the viewer of the tenuous nature of postwar Central America, in which the long-discussed project of modernity has not yet caught up with the advances of more sophisticated societies or their space programs. As opposed to the traditional presentation found in prestigious art galleries, Third World Sputnik seems to delight in a willing indifference to the formal rules of exhibition. One does not expect to find a spacecraft made from trash in an art gallery, and the scattering of leaves, spare parts, bottle caps, and unconnected hoses at the base of the structure emphasize a certain creative freedom not permitted in the high culture of the First World.

As a commentary on neoliberalism in Central America, Third World Sputnik is both a painful reminder of the economic failures of recent years and a reflection of the individual desire to survive in an unforgiving society. The failures of neoliberalism are apparent in the design and materials used in construction: in this craft there is neither the funding nor the expertise available to construct an exterior shell of technically advanced materials able to withstand the harsh vacuum of space. In its place the assembly of flattened beer cans cut in hexagonal designs must suffice. Between the uncovered surfaces of the capsule and the bare wood underneath, a small tree pokes out above an ill-fitting window.

Despite the obvious commentary on poverty and technological backwardness, the capsule demonstrates the ingenuity of the individual to make due in a menacing environment. In a neoliberal society defined by deregulation and the disappearance of governmental assistance or welfare programs, individuals are left to fend for themselves and create their own opportunities in increasingly expanding informal and unregulated economies. Thus, one can imagine the Third World rocket scientist slowly building his contraption from the leftovers and spoiled discards found in the trash. Although the technical knowhow is sorely lacking, Third World Sputnik reveals the desire and ingenuity to participate in contemporary technological advancements even when the basic materials needed are unavailable. Even without the scientific skills and economic infrastructure in place to support a space program, this sculpture demonstrates the persistent creative attitude of those who both imitate the technological creations of the First World and are constrained by the failings of present day economic and governmental policies.

Like the Third World Sputnik, the design from discarded materials and symbolic meaning of Vega’s Third World Rovers (titled Exploradores ambulantes del 3er mundo in the original Spanish) seeks to critique the economic, social, and political underdevelopment of modernity of Central America. In recent years highly sophisticated scientific landers sent to Mars have made exciting discoveries of the planet. These landers are able to analyze soil for its chemical content, take high-resolution pictures, and navigate the rough terrain of the Martian planet with a high degree of precision. The landers presented by Vega, however, are capable of none of these technological feats. Yet they still display the innate desire to explore the outside world by whatever means available. Instead of precision instruments and high-tech cameras, the limbs of these Third World rovers hold in place brushes and bottle caps that serve as yet another reminder of the technical limitations and will to create which permeates Tropical Space Proyectos.

In the spring and summer of 2014, Third World Rovers was part of an exhibit at San José, Costa Rica’s Contemporary Museum of Art and Design (Museo de Arte y Diseño Contemporáneo, or MADC). Titled “El día que nos hicimos contemporáneos” (“The Day We Became Contemporary”), the collection was centered on the question of modernity in Latin America and focused on a wide variety of Central American artists and their approximations of what it means to be contemporary in a region struggling to keep up with the technological advancements and cultural interference of the United States. Pertinent themes of migration, violence, unchecked crime, and a frustrated search for a personal and national identity are seen as the primary inspiration for the more than 60 works that comment on modernity in the region. Like the Tropical Space Proyectos sculptures of Simón Vega, the exhibit both skewers a lack of technological advancement and provides inventive alternatives to fill the cultural spaces between the alleged First and Third Worlds.

Seth Roberts is a doctoral candidate at the University of Alabama and studies contemporary Central America with a focus on the art and literature of the postwar period. He also writes on Peruvian fiction, exile studies, and the social and linguistic dynamics of baseball in the United States.

Bibliography

Andrei Ibarra, Karlo. Prototaxis. 2013. The Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, San José, Costa Rica.

Castellanos Moya, Horacio. “El cadáver es el mensaje: Apuntes personales sobre literatura y violencia.”

Gammage, Sarah. “El Salvador: Despite End to Civil War, Emigration Continues.” Migrationpolicy.org. Migration Policy Institute. 26 July 2007. Web. 25 March 2014.

Hershberg, Eric and Fred Rosen. “Turning the Tide?” Latin America after Neoliberalism. Turning the Tide in the 21st Century? Eds. Hershberg, Eric and Fred Rosen. New York: The New Press, 2006. 1-25. Print.

Istmo: Revista Virtual de Estudios Literarios y Culturales Centroamericanos 17 (2008). 24 September 2013. http://istmo.denison.edu/.

McAllister, Carlota and Diane M. Nelson. “Aftermath. Harvests of Violence and Histories of the Future.” War by Other Means. Aftermath in Post-Genocide Guatemala. Eds. Carlota McAllister and Diane M. Nelson. Durham and London: Duke UP, 2013. 1-45. Print.

Vega, Simón. Imperial Slum Ship. 2013. 43rd S(I)NA. Medellín, Colombia. Tropical Space Proyectos. 1 September 2014. simon-vega.blogspot.com 1 March 2015.

---. Third World Sputnik. 2013. 55th Venice Biennial, Venice, Italy. Tropical Space Proyectos. 1 September 2014. simon-vega.blogspot.com 1 March 2015.

---. Tropical Mercury Capsule. 2012. MARTE Museum, San Salvador, El Salvador. Tropical Space Proyectos. 1 September 2014. simon-vega.blogspot.com 1 March 2015.

---. Rover Explorers of the Third World. 2010. The Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, San José, Costa Rica.