December 28, 2016

Willem Boshoff's Visual Lists: A Personal Plea for Cultural Preservation

Written by Antonia Dapena-Tretter

Willem Boshoff is a well-known South African text artist with an undeniable passion for the written word. In most of his artworks, language is represented through the Roman alphabet, but even when this is not the case—as with a handful of works showcasing complicated codes, or carved sculptures with little to no incorporated symbols—Boshoff still expects his art to be read. Correcting a former student who referred to his work as “bookish,” Boshoff claimed that his projects are not just book-like; they are, in fact, books (Paton, chapter 3, unpaginated). As supposedly translatable objects, Boshoff's assorted artworks communicate a definite narrative to his audience, but, should there be any confusion as to his intentions, he also offers access to rather lengthy explanations of his many projects through his website: www.willemboshoff.com. The abundance of materials available suggests a possible insecurity on the part of the artist to allow his works to stand alone, but it might also express Boshoff's compulsion to communicate and the urgency of his message. Reading through his portfolio and corresponding artist statements, one becomes acquainted with a man whose love for books and language is equally rivaled by his hatred of dogma or intellectual power plays that cannot be severed from their imperialistic roots. His art-making practice stems from South Africa's colonial history as much as its landscape, the two necessarily intertwined, with the artist selecting his art-making materials (sand, granite, and wood) from the world around him. Recognizing a long-standing linguistic link between text and texture, Boshoff sees no disconnect between these natural resources and the medium of language. In one of the abundant artist statements published on his website, Boshoff explains further:

To me, the experience of the languages I speak is like traveling through the landscape I grew up in, the landscape I love and know so well. The trees and plants are mostly familiar to me, but every now and then I spot a rare and curious species. It usually makes me stop dead in my tracks and makes me reach for my camera and identification manuals. When I read a text and I see a word that I have not yet encountered, I get thoroughly excited…I have often worked with the extinction of plants and trees in my artworks and in a way I am trying to save old and difficult words from vanishing.

A close look at this theme of extinction reveals an artist fighting to preserve South Africa's diverse cultural landscape in the face of a forcefully imposed homogeneity from abroad. Calling himself a “linguistic terrorist,” Boshoff stresses not only that he has claimed all languages as a weapon in an artistic war against cultural hegemony, but also that that his tactics are unconventional. They are not those of a soldier, but rather a rouge terrorist, disarming his viewers one piece at a time (Ho 13). Out of necessity, Boshoff has learned English, but his first language is Afrikaans, a South African dialect of Dutch that originated in the 17th century.[1] Both Afrikaans and English have a role to play in Boshoff's art practice but they do so alongside the nine national Bantu languages—Ndebele, Northern Sotho, Sotho, Swazi, Tswana, Tsonga, Venda, Xhosa, and Zulu—not recognized by the South African government until 1994. Allowing indigenous languages equal playing time is an obvious celebration of his country's unique linguistic variety, a fragile cultural asset at risk of vanishing under the pressures of Westernization. His purposeful attention to multiplicity in general, an inescapable feature of the list, responds broadly to the threat of cultural extinction, but Boshoff's verbal lists have additional subversive power in their ability to expose the subjective nature of Western knowledge, disseminated since the age of the Enlightenment through highly partisan dictionaries, encyclopedias, and scientific classifications. The following investigation will unpack Boshoff's artistic reaction to global hegemonic control, the South African diversities threatened, and language as an important instrument of cultural identity and subversion. Ultimately, Boshoff uses the hegemony of language itself as a tool to subvert the hegemonic power structures that have long affected South Africa—from British imperialism to globalism under the unofficial reign of the United States.

South Africa Under Cultural Hegemony

The current world-model established by the West is based around an Anglo-American implied domination, arguably with some limited power-sharing among a controlled handful of European countries. Most other nations have been lumped together under the flawed, and frequently problematized, description of the “tricontinental third world” (Ankerl 135). The concept was invented during the Cold War to describe so-called developing countries struggling to maintain economic stability, but, in general, post-colonial theorists take issue with the term for its ability to imply a distinctly lesser rank than those countries fortunate enough to have been labeled “first” or “second world.” Guy Ankerl, on the other hand, argues in his book Global Communication Without Universal Civilization that while unfortunate, third world is an apt description for these peripheral nations kept apart from the rest of Western civilization (145). After all, it is the Western world that in an all-too-common instance of binary thought began to define itself in cultural opposition to the non-West, a tendency dating back at least to the classical period of colonialism.

This Anglo-American privilege is revealed perhaps most concretely through mapping practices. Adam Gopnik of The New Yorker asserts that “[w]e can know the shape of the planet only through maps—maps in the ordinary glove-compartment sense, maps in a broader metaphoric one—and those maps are made by minds attuned to the relations of power” (unpaginated). One need only consider the beginnings of longitudinal measurement for tangible proof. While latitudinal coordinates have always been gaged against the Equator, until 1883, each country chose for itself a point from which to measure longitude. It was the United States government that called for a unified system of measurement, and, at a conference held in Washington, it was decided that Britain should serve as a the globe's single prime meridian. They settled upon Greenwich, at which point the rest of the world was forever forced to measure its location relative to England (Ankerl 249). The choice was seen as practical, with the British Empire having encompassed Australia, New-Zealand, India, Pakistan, Burma, Sri Lanka, Egypt, Kenya, Hong Kong, Ireland, Canada, the US East Coast, some areas of the Arabian desert, a few small islands in the Atlantic and Indian oceans, and, of course, South Africa.

South Africa must be viewed as part of the non-western amalgamation, changing “ownership” more than once since its preliminary European occupation. Because the ability to communicate is a keen indicator of cultural cohesion—representing a people's collective knowledge, traditions, and myths—civilizations to avoid colonization tend to demonstrate one unified race and language (Ankerl 6). South Africa is particularly susceptible to outside control due to its divided population with innumerable dialects. Lacking a core culture to retaliate against a unified invasion, in 1652 South Africa witnessed its first European settlers in the form of a small group of Dutch farmers. An English presence was not far behind with the strategic invasion of 1795—a significant military effort to prevent the French from circumnavigating the Cape. However, as the Dutch had already staked a claim, no formal attempt to colonize was made until the early nineteenth century, when, as a direct result of the Congress of Vienna, the British government was given its first Cape colony. Within the next decade the largest English-speaking group of settlers, approximately five thousand people, arrived in South Africa with official land grants from the motherland (Hickey 370-371). As expected, power struggles between the Dutch and English erupted almost instantly, with the first Anglo-Boer War officially declared in 1880. While the British Empire was strictly at war with the Boers—an Afrikaans word to describe the Dutch farming population believed to be a threat to a British imperial dominance—the black South African population could not avoid the conflict. As a consequence, the first and second Anglo-Boer wars are often referred to together as the “South African Wars,” a vague but probably more accurate assessment of the violent cultural clash.

Boshoff has responded to the South African Wars specifically with works such as 32,000 Darling Little Nuisances (2003), Far Far Away (2004) and Vexillator (2007), but has been properly criticized for a perceived bias toward his Dutch ancestry. There is an attempt made to overcome this prejudice in Writing that Fell Off the Wall (1997), a powerful piece geared at exposing the extremely problematic nature of colonialism in general.[2] The installation fills a room with seven small walls projecting perpendicularly out into the center of the space on either side. They resemble temporary partitions put up by a museum for a short-term exhibition, and Boshoff's audience, surely well-versed in museum practice, would know exactly how to engage with such walls and text panels were it not for the artist's decision to represent the language normally on the walls as having fallen off, demoted to the floor.

The scattered language is hardly arbitrary and has been grouped specifically to display one word per wall, represented in a total of seven different Western languages. Boshoff translates each word, for example “purity,” into English, Dutch, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and French. Each language makes reference to a different colonial power at work in Africa during the period of New Imperialism when European nations participated aggressively in a race for African territory and natural resources. This time has been referred to most commonly as the “Scramble for Africa,” but also occasionally as the “Partition of Africa,” an acknowledgment of the many lines drawn and borders created throughout the continent. Robert E. Harrist Jr. envisions the now segmented land masses in terms of “landscapes [that] come into being when fragments of the otherwise-undifferentiated continuum of the surface of the earth are set apart and encoded with meaning by human viewers” (18). Like Harrist's sentiment, Writing that Fell Off the Wall also expresses the man-made nature of the global puzzle. Boshoff's decision to use a series of partitions jutting into the exhibition space—a direct reference to the “Partition of Africa”—rather than the far simpler option to work with the pre-existing exterior walls, suggests an intentional move on the part of the artist to represent Africa's artificially split landscape.

The words chosen for inclusion, like both the languages represented and method of display, are highly purposeful. The list contains the already noted translations for each of the following English words: Truth, Identity, Boundary, Order, Faith, Purity, Reason, Destiny, Progress, Salvation, Purpose, Standard, and Perfection. As with boundaries, truth is constructed, and Boshoff's list holds together as a series of like essentialist abstractions promoted in order to justify the subjugation of Africa. Passionately, Boshoff expounds on the subject:

With one hand they offered a 'truth that sets one free' and in the other they captured slaves… Africa's diamonds still feature in the crown jewels, and much of its soil and rights are owned from abroad, but its roots are free. It alone will find a way of picking up the pieces from its own shattered past, left abandoned by the failed promises of its former masters. (http://www.willemboshoff.com/)

This quotation pointedly articulates some of the ways that the South African landscape—its diamonds, its soils—was mined under colonialism for the British benefit, but Boshoff also turns his focus to the present. He does not call for South Africa to forget its past, but rather, to acknowledge the damage done and to rebuild. After all, to forget would be impossible, Boshoff tells us in another artist statement. He cites his neighborhood, containing street signs honoring the former British monarchy at every major intersection, as proof. These cultural markers exemplify that while “[e]mpires have a way of coming to an end [they] leav[e] behind their landscapes as relics and ruins” (Mitchell 19). Past colonial conditions did not vanish with the evacuation of governmental control; instead, they have a tendency to bleed into the present.

Like Boshoff, Cuban curator and critic Gerardo Mosquera practices in the periphery, and from his vantage point as a Hispanic scholar, he is intensely concerned with lingering traces of colonialism under the present condition of globalization. “Globalisation,” he tells us, “is only possible in a world that has been previously reorganized by colonialism” (Mosquera 18). These hegemonic power structures remain in place but function more discreetly through cultural rather than physical invasions. Through mechanisms such as the inescapable Internet, trans-continental sharing is possible, but the exchange is relatively one-sided. As the globe shrinks, it is necessary for there to be certain common practices, as was decided at the Prime Meridian conference at the turn of the century, but there is a real fear that globalization will bring with it a homogenized Euro-American culture, erasing much, if not all, previous diversity.

Mosquera identifies the United States as the primary launch-pad for Western cultural dissemination and its resulting sameness. With an ever-increasing population of Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans, the United States has a real opportunity to embrace multiculturalism through a bilingual platform. However, even in communities largely comprised of Spanish-speaking immigrants, official communications are practiced strictly in English (Ankerl 161). Mosquera gives additional evidence that the Anglo-American collective reigns supreme: “Today even dogs are trained in English, and it is said that they understand this language better than any other” (18). It is both absurd and telling that people would justify the propagation of one language over another in such a way. Language-use suggests a certain type of domination, and American Anglophones undeniably resist any power-sharing with their Hispanic citizens. To join the American “melting pot,” as the idiom suggests, it is necessary to blend-in, sacrificing cultural difference. It is one thing for this expectation to persist on American soil, but Boshoff, situated over 13,000 kilometers away, recognizes a pervasive American desire to propagate on an international level:

The Romans conquered Palestine, England, and the rest of Europe. The Catholic Church then supplanted the Romans, and the Vatican became the seat of power. European countries like Britain and Spain perpetuated the spirit of conquest by colonising large parts of the world. And now, the ethos of the Roman invaders has been passed on, to the Americans. (http://www.willemboshoff.com/)

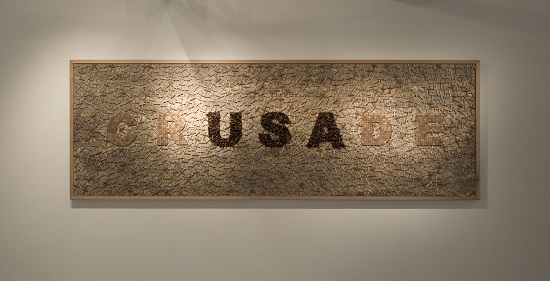

This is written in explanation of Boshoff's 2004 artwork, Crusade, but could just as easily apply to Liberté Égalité (2004), What is our oil doing under their sand? (2004), and Swat (2011), artworks exposing America's contemporary variation on the no-longer politically correct theory of manifest destiny.[3]

In Crusade, Boshoff reacts to former American president G.W. Bush's unfortunate comparison of the United States’ war against Al Qaeda to a crusade, complete with all the word's historic baggage. The piece, like much of Boshoff's art, is a text work, a relief of the word “crusade” itself. The artist fashioned the text out of wood, choosing darker varieties for the letters U, S, and A, embedded within the larger word, emphasizing an inherent connection between America and its proselytizing cultural mission.[4] The background is covered with crosses, obvious symbols of Christianity, but the informed viewer recognizes that with the expansion of scripture comes also script. The widespread adoption of the Roman alphabet followed in the wake of the New Testament and facilitated, through language, the movement of several types of Western knowledge and culture (Ankerl 69). In other words, the crusade for sameness goes far beyond religious cohesion.

A closer look at Crusade in terms of its medium indicates an additional concern for Boshoff, that is the potential loss of biodiversity under South Africa's continued exposure to outside influences. The dark-colored woods—African Rosewood, Kiaat, Partridge, Zebrawood, Stinkwood, and Zimbabwean Teak—serve a practical function, enabling the viewer to read USA as separate from the rest of the word, but this pragmatic explanation does not account for the additional variety represented in at least ten different kinds of trees. We have located Boshoff's list, but what does it mean? The multiplicity of rare woods contrasts starkly with the plywood background, a fabricated wood substitute made with thin splices of pine held together by glue, pressed and heated to extreme temperatures. The processed wood stands as a symbol of capitalism, manufactured and sold cheaply, and seems to suggest a choice to the viewer: do we protect South Africa's natural biodiversity or settle for the alternative?

Preserving South African Diversity

Landscapes in general are at risk, seen as “endangered species that have to be protected from and by civilizations” (Mitchell 20). The simple answer to the dilemma of disappearing landscapes, setting aside “wilderness areas,” certainly helps to prevent the growth of industry and urban sprawl, but will not save an environment's natural biodiversity. A 1999 scientific study, performed at the Institute for Plant Conservation at the University of Cape Town, found that South African plants were under attack by numerous invasive plant species, jeopardizing one of the world's most diverse environments (Higgins 303). The Institute's goal was to develop a feasible strategy to eradicate alien plants in order to protect native species. Ultimately, the conclusion was reached that the most effective measure to preserve biodiversity is to prevent the introduction of alien species in the first place, a near impossibility with today's frequent international exchange (Higgins 304).[5]

Interested in learning more about his country's living landscape, in 1982, Boshoff became a member of the South African Dendrological Society, an organization devoted to the scientific study of woody plants. Participation in the group would greatly assist Boshoff with his artistic goal to catalogue a different kind of tree for every day of 1982 (Vladisclavic 82). Each arboreal specimen was to be carved with an intricate unrecognizable code; while the language cannot be understood, the work, called simply the 370-Day Project (1982-1983), oddly still functions as a comprehensive tree encyclopedia.[6] Its ability to convey the diversity of South African trees through texture and color alone seems to suggest the pointlessness of taxonomy—an historically Western study to classify all aspects of the global environment. Since then, the artist has continued his personal quest to seek out individual plants in the South African landscape, memorizing their assorted names and locations as a way of cultivating a mental garden of sorts.

The scope of Boshoff's plant list can only be grasped after viewing its physical manifestation as a Garden of Words (1982 – ongoing). The most recent iteration, Garden of Words III, has over 15,000 different plants represented.[7] The artist aims to reach 30,000 entries to surpass the current number of endangered plants on the IUCN's Red List, but rather than depicting the plants already memorialized on the Red List itself, Boshoff chose to portray the South African landscape specifically. He selects each specimen for exhibition from the particular species he has personally encountered in the local landscape. The final effect is a complete reversal of Boshoff's earlier cataloguing attempt made through the 370 Day Project. In this almost overwhelming, seemingly endless, man-made garden, each plant loses all distinguishing features with the exception of its linguistic label. Every specimen is named on a flexible white cloth with both the Latin and common names featured. Among the scientific community, Latin names tend to be privileged as a global standard. For categorical purposes this makes sense as the common or indigenous names do vary greatly, even within small geographic areas, and many plants are known to have more than one. Naming practices—“the right to speak and to be heard, the right to name and have that name 'stick'” (Tuan 685)—have a way of revealing cultural domination, and as seventeenth and eighteenth century Europeans gained access to new continents, they feverishly assigned names, recorded descriptions in their travel logs, and collected plant specimens for an eager audience at home (Editing the Image 10). It is in this incredibly constructed way that “[p]lants and animals become part of the human socioeconomic order” (Tuan 686). Boshoff purposefully retains the local name and plant location in order to remove the privilege assigned to the Latin name, an Imperial marker, while retaining each species' connection to the local landscape, no matter where the garden may tour. One cannot help but notice that despite the total lack of identification labels, Boshoff's 370-Day Project reflects the natural variety of South African trees in an equally effective manner, but, because the artist incorporated an unintelligible text into the work, the overall message is not as clear-cut as in Boshoff's later Garden of Words. Here the artist obviously continues his ongoing investigation into the hegemony of language but he has simultaneously managed to commemorate local biodiversity in a grand memorial to native plants nearing extinction.

Describing his interest in extinction more broadly in an essay written for a high-profile show—Inscribing Meaning: Writing and Graphic Systems in African Art—at the National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C., Boshoff notes:

My work deals primarily with loss. It points to the abject extinction of a people's collective myths and oral traditions—and to the loss of the unique cultural and aesthetic qualities that a particular language brings to these narratives—when they are no longer shared by word of mouth.(54)

Put otherwise, there is a common thread through much of Boshoff's oeuvre, an attention to cultural loss, and more specifically to the loss felt with the disappearance of languages as expressions of cultural nuance. South Africa's eleven national languages together shape its cultural landscape and create a highly diverse narrative. With many of these indigenous languages at the brink of extinction, as with the loss of biodiversity, the effect is an unfortunate flattening, an evening-out of South Africa's distinctly heterogeneous culture.

With an aim to demonstrate the importance of linguistic multiplicity, Boshoff returns frequently to the Christian explanation for the world's many languages told through the Genesis tale of the destruction of the tower of Babel. In both Children of the Stars (2009) and Lebab (2004), Boshoff simply lists the Biblical text over and over in as many different languages as possible, focusing with extra care to represent those already extinct, such as a number of Khoisan dialects and Amharic. Where one might expect the artist to offer some clarity, Boshoff instead raises a cryptic question: “Why, in the story of Babel, was it better for the people representing the ideal of 'real' alliance, striving to be the 'mightiest nation on earth,' to be deprived of their domineering monolingualism and uniculturalism?” (Inscribing Meaning 156). While an explicit answer does not exist within the catalogue essay, by using the word “domineering,” Boshoff reveals his true feelings.

Given that the artist makes reference to philosopher Jacques Derrida earlier in the text, it seems safe to assume that he would have been familiar with Derrida's critical analysis of Babel, Des Tours de Babel, carefully translated in a Joseph F. Graham collection centered entirely around issues of translation. Through Graham's text, Derrida tells us that God “ruptures the rational transparency [afforded by a universal language] but interrupts also the colonial violence or the linguistic imperialism” implicit in the tale. Further refining his interpretation, the philosopher plainly states that through the birth of lingual multiplicity God ensured that the world would “no longer be subject to the rule of a particular nation” (Graham 226). It is in light of this revelation that Boshoff's backwards title makes the most sense. As he inverted the letters of the word Babel to form the title Lebab, so too did the artist reverse the numbers assigned to the Biblical story (chapter 11, verse 9) to make 9:11—the date of the unprecedented terrorist attack on the New York City Twin Towers.[8]

The connection, while obscure, seems to satisfy the artist, allowing him to draw parallels between the “domineering” people of Babel and those of a twentieth-century United States. Having previously considered the American role in globalization and cultural homogeneity, there may be validity to Boshoff's claim. The English language assault tends to be met with the most resistance in cultures unified under Islam. Noting that international terrorist efforts, such as those that brought about the 9/11 attack, are frequently headquartered in the Middle East, African and Islamic cultural expert Ali A. Mazrui is convinced that the heightened presence of Muslims in the Western world alone has the potential to reverse the effects of homogenization, offering an equally potent cultural package with its own moral code, religious beliefs, unique alphabet, and language (Unpacking Europe 102).

The Power of Language

While not every nation can resist Westernization with the same force, most civilizations oppose lingual assimilation by striving to preserve their cultural identity through the safeguarding of the everyday use, or official designation, of their particular mother tongue, becoming understandably protective should they perceive even the slightest decline. However, if the goal is preservation, attention must shift away from oral communications toward written text, understood to be a more permanent record of a language than the corresponding oral (read ephemeral) tradition.[9] With a focus on cross-cultural communication, Ankerl articulates what he perceives to be the three main functions of text within a civilization:

-fixing (mnemonically) the content of a message across vernaculars, dialects and beyond,

as well as

-preserving, perpetuating it beyond “the verb,” the oral tradition for (transportable) visual or tactile perception, and

-extending its “empire” over (spoken) languages and their variations.(61)

Apparently, it is precisely because of its static qualities that script is preferred over word of mouth for anything that a society deems worthy of remembrance, such as a constitution or holy book.

Boshoff comprehends oral language in terms of movement and draws a comparison to the ever-changing wind in his 2008 outdoor installation Windwoorde. The metaphor continues with his observation that wind is actually air in motion and cannot be seen but through the rustle of trees and its other surroundings. He writes: “Just like the wind needs the anchor of trees, buildings, and leaves to be heard, so too are languages and thought dependent on text, speech and our will to share for their preservation” (Boshoff website). The analogy—language is to text as wind is to trees—is beautiful and speaks to both the impermanence of the oral tradition and the inherent fixed qualities of the written word.[10] Boshoff tends to describe his art practice as simply “language art,” as opposed to the oft-used description “text art,” striving to show no preference toward either the written or oral manifestations of language.

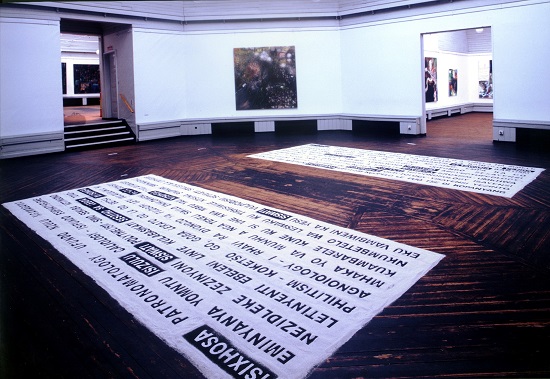

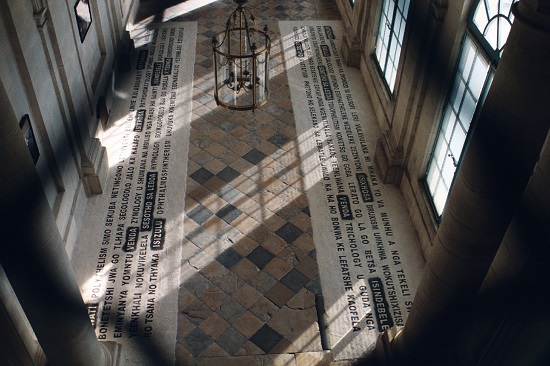

As physical art projects, however, it is difficult for Boshoff to express the ephemerality of the wind without the permanence of trees. An attempt, Writing in the Sand (2000), is perhaps Boshoff's most celebrated artwork to date, exploring both the preservation and impermanence of language.[11] Telling us that “[t]he ground is as much an ‘open book’ with instructions to follow as any randomly opened book” (Boshoff website), the artist places his text, written in both black and white sands and composed primarily of indigenous African languages, scrawled across the floor. It is common practice for Boshoff to collect his sands from the South African landscape, bottling two-hundred different varieties for his 2001 installation, Uhmlabathi. In Writing in the Sand, as the name suggests, the material is not meant to be safely secured in bottles, but becomes a medium through which the artist underscores the piece's own impermanence. The words are constructed painstakingly through the use of stencils, only to be swept away at the end of the show. Ivan Vladisclavic, author of the only book written on the artist that is not an exhibition catalogue, conveys this ephemerality in terms of mortality, citing the old adage “dust to dust, ashes to ashes” (65). While not incorrect, this explanation fails to consider the work's connection to South Africa and its lasting impact on an audience, more frequently than not, composed entirely of locals. Boshoff means to frustrate a large portion of South African visitors, those that speak English exclusively, by listing difficult or marginalized English words, followed by their definitions in a lesser-known, but also nationally recognized, South African language.

The discomfort of being surrounded by words that one does not know cannot be alleviated without outside assistance. Boshoff hopes that the work will be a conversation starter between English-speakers who generally have the upper hand, and native South Africans who are proud of their ability to speak one or more of the country's Bantu languages, but rarely have the opportunity to share it. The English words are selected for their obscurity, but also to bring a smile to the face once the meaning has been discovered (Snyman 84). Boshoff knows that the interaction between visitors will be brief but hopes to create an amicable meeting ground through the discussion of words such as polythelism (having more than two nipples), caliology (the study of birds' nests) and pognology (the study of beards)” (Vladisclavic 64).

Boshoff likes to upset the natural order of things by removing the privileged status afforded to most English-speakers. As an Afrikaans-speaker in what Boshoff has described as a predominantly English-speaking environment, the artist felt continuously judged by his peers and work associates. They were quick to assume that because he spoke English with a thick Afrikaans accent, he was uneducated, or worse yet, stupid.[12] To prove them wrong, Boshoff began to study dictionaries, learning words to defend himself against what he has called the “language intelligentsia” (Vladisclavic 48). It has been years since this sort of incident has plagued the artist, but Boshoff has not stopped scouring books for linguistic ammunition, reading and annotating the Oxford English Dictionary for hours at a time (Inscribing Meaning 218).[13]

Boshoff has a heightened sense of awareness when it comes to the hegemony of language and knows better than to view the Oxford English Dictionary as a passive collection of definitions. In 1916, the Oxford University Press published a pamphlet to announce the highly anticipated release of its second edition of the O.E.D., the first having been published in 1884. As an advertising tool, the document is to be expected to contain a certain amount of self-praise, but by referring to its product as “an Imperial Asset,” it manages to take boasting to international levels. Making similarly grand claims, the pamphlet further reported that “in its exhibition of the language as a living and growing thing closely connected with the history of the nation, [the O.E.D] will yet have its greatest value for the British Empire and the whole English-speaking race” (Brewer 3-4). The London-based Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science, and Art—a magazine released each week since its 1855 birth—extolled the dictionary as a “wonderful storehouse of our native language,” with the unsaid hope that it would advance the English-speaking mission and culture abroad. The Asiatic Quarterly Review agreed wholeheartedly and proclaimed with more transparency:

A work of such magnificent proportions…should be the most coveted possession of all public libraries in the United Kingdom, in the Colonies, and at least the headquarters of every district in India and at her principal Colleges. It is not so much a Dictionary as a History of English speech and thought from its infancy to the present day. (Brewer 4)

Key to the O.E.D's nineteenth-century reception was the dictionary's ability to export the English language, glory, and history to its colonies, acting as imperial PR to civilizations perhaps not convinced of the merits of the English way of life. No dictionary anywhere in the world could compare to the completeness of the O.E.D., boasting a collection of five million passages reproduced from literary works spanning the past seven-hundred years. It had taken decades to produce, but the English had finished their linguistic compilation before the Germans and Dutch, who were, as of 1928, still hard at work on the Grimm Brother's dictionary and the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal respectively (Brewer 8). Like the 1960s race to be the first nation to land on the moon, a cultural accomplishment of such grandeur would help to maintain the English hegemonic status, that which Boshoff aims to destroy.

Tom MacAuthor reminds us “that the compilers of the hard-word dictionaries were not recorders of usage, as lexicographers are nowadays largely assumed to be. Instead, they were themselves partisan” (MacAuthor quoted in Nagy 440). As not all words could be recorded in a standard dictionary, early examples show a frequency of certain types of words over others, an attempt to promote “power words” of the time (Nagy 445). Even in the case of the O.E.D.—a project designed to be as complete as possible—choices, in the form of strict guidelines for inclusion, were still necessary. Words were to be selected from published texts, the implication being that if a word was “fit to print” it was fit for inclusion. This method of selection clearly privileges the written word over spoken language and the words used by educated men (those who were producing the published texts) over the lower and/or illiterate populations. Consequently, the finished product is guaranteed a certain level of sophistication but can hardly be seen as a mirror of society at large (Nagy 443).

Here, Boshoff finds the opportunity to exploit the masked subjectivity of texts, and perhaps in precise acknowledgement of the hegemony of language, he stakes a claim to unusual and complicated words by personally writing over fifty different dictionaries, and additionally compiling over two-hundred and fifty.[14] His writing method is explained in the following quotation and highlights first and foremost the very subjective nature of dictionary compilation:

I wrote my first dictionary in 1977—Dictionary of Colour. Since then I have written quite a number of them. The biggest one, with over 18,000 entries, was completed in 1999 – A Dictionary of Perplexing English… I made careful notes on all the words I usually found puzzling and obscure and turned them into dictionary entries. I tried to give each word a “face” so that it might become endearing and desirable. I gave its meanings, wrote a little of its etymology, related anecdotes and gave examples of its usage. (http://www.willemboshoff.com/)

Recognizing Boshoff's role in the production of these dictionaries is central to an understanding of their subversive qualities. He alone possesses the power to make important decisions: which words to include and what definitions to assign them. The Dictionary of Perplexing English, for instance, is comprised of words that can only be said to have once perplexed the artist personally (Vladisclavic 52). Boshoff creates these books not for publication (as of yet anyway) but rather for inclusion in his many art projects: Writing in the Sand (2000), Windfall (2001), Sdrow fo nwodkaerb (2004), Words in the Sky (2010), Oh No! Dictionary Prints (2011), among others.

While Blind Alphabet Project (1990 – ongoing) is completely based on definitions taken from the O.E.D, the artist is careful to point out that projects begun more recently are entirely inspired by his own various dictionary definitions. Moonwords (2005) is the only exception to the rule, making use of anthropologist and philologist Dorothea Blake's Bushman Dictionary, published posthumously in 1956. This book, with over thirty-eight definitions for the word moon, represents a curious, early example of an effort to understand the now-almost-extinct African languages of the Khoisan peoples (Boshoff website). Blake's decision to preserve these various Khoisan dialects stands in opposition to the imperial goals celebrated around the publication of the O.E.D. As such, the Bushman Dictionary continues to speak (long after Blake's death) to Boshoff's mission for South African cultural preservation. Saved in text, those thirty-eight Khoisan words for moon will not be forgotten, and Boshoff makes doubly sure by reproducing them in Moonwords and writing about them on his website: “The words are arranged in and around moon-like shapes to function as 'stars in the night-sky'. As with the Khoisan language, the fire-works of word-stars light up the sky to blink out forever.”[15] It is imperative that such things be recorded if they are to be remembered, because, as Professor Ian McLean tells us, hybridity, while certainly “an oppressive instrument that erases difference,” is “also a fact of life” (300).

Conclusions

It is true that Boshoff has not set language free, but allegations of complicity fail to consider the way in which it is used and the reason for its captivity. The artist has claimed text as a weapon in his various attempts to reverse global hegemonic power structures; Boshoff's art fights fire with fire. Perusing the sorts of words chosen for his many dictionaries adds additional transparency to Boshoff's end-goal. The Dictionary of -ologies and -isms, for example, ought to be filled with a long list of ideologies, distinguished by their -ism suffix, but these words are not included; they do not need Boshoff's assistance to survive. Indeed, perhaps it is because the Western world claims responsibility for all modern ideologies—liberalism, capitalism, socialism, Marxism, fascism, Nazism, and capitalism (Unpacking Europe 99)—that they are omitted from Boshoff's list. Language-use under the artist's control no longer privileges Western “power words.”

This is all part of Boshoff's plan to remove South Africa, and the rest of the non-western world, from the lowly designation of a geographic periphery. Carrol Clarkson misses the mark when she interprets Boshoff's dictionary definition for the word “disoccident” as a reflection of the artist's desire to lose himself in a book (107-108). The definition—“to be unsure of which way the west is; to be confused about the four wind directions on a compass”—is surely printed in Boshoff's 2004 Nonplussed exhibition catalogue as part of the artist's campaign to change our global focus away from the Western world exclusively, to purposefully disorient ourselves. McLean, quoting Nikos Papastergiadis at a July 2001 conference in Sydney, Australia, writes: “When we look outside our cultural space in which direction do we look? Up, down, to the side? Do we look towards the force that is above us [by which he meant Europe and the USA, not Asia]? Or do we seek to find something in the space that is adjacent to us [he named New Zealand and South Africa]?” (304). Boshoff fights, through his art, to redirect attention away from Papastergiadis' “above,” as defined by McLean as Europe and the United States, toward other spaces, more specifically toward his home country of South Africa.

Boshoff's preference for multiplicity, expressed through his incorporation of different kinds of lists, is a very targeted undertaking to highlight his country's diversity. His material lists—several kinds of woods, sands, and rocks—explore South Africa's rich natural resources and landscape (those very items that attracted European colonialists in the first place) and offer a new taxonomy focussed on the local. His verbal lists have the ability, as with any texts, to preserve the items listed, but their subversive powers concurrently expose the destructive hegemony at work in the simple act of naming. Whether safeguarding the perpetuation of abstruse English words or at-risk “survivor languages,” Boshoff seems to resist the notion of natural selection—the survival of the fittest—in favor of variance. Inarguably, Boshoff's ideal world is not one-sided but multifaceted, and his artworks spread a corresponding message of pluralism and diversity in hopes of bringing about a more humane global society—one that protects the rights of smaller civilizations to maintain their differences, to exist separate from the homogenous cultural conglomerate.

With an MA in Art History from The University of Toronto, Antonia Dapena-Tretter writes about modern and contemporary art. Her articles have been published in sources such as The Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, The Lincoln Humanities Journal, Droste Effect Magazine, and African Arts.

A shorter version of this article was published in African Arts, Volume 47, number 3. Autumn 2014, MIT Press.

[1] Considering its central role throughout South Africa's period of Apartheid, Afrikaans may never clear its name of certain oppressive implications. However, given its ever-increasing marginal status, Boshoff has begun to treat it as one of the many “survivor languages,” at risk of vanishing in the near future. In certain instances when the artist has not used Afrikaans, he has been criticized for the choice, for example Mark Auslander's assessment of Boshoff's 1997 Abamfusa Lawula: The Purple Shall Govern. The critic states in his review of the piece: “Ironically, this self-consciously inclusive work could be read as complicit in the widespread national assault on Afrikaans” (622).

[2] See the artist's website < http://www.willemboshoff.com/documents/artworks/writing_that_fell_off_the_wall.htm > for images of the installation and informative details.

[3] The online Oxford English Dictionary defines manifest destiny as “the doctrine of belief that the expansion of the United States throughout the American continents was both justified and inevitable.”

[4 ]The artist's website < http://www.willemboshoff.com/documents/artworks/CRUSADE.htm > is again useful for a more complete visual of the work.

[5] Invasive species are generally introduced without the knowledge of their carriers. The American Chestnut tree is a perfect example of an indigenous plant species that was virtually wiped out from its native continent of North America after the unintentional release of an exotic fungus from Asia, now known as the Chestnut blight. According to the American Chestnut Foundation, this variety of tree comprised nearly 25% of the 1950s forests, a landscape now severely altered by their absence.

[6] Refer to the artist's website < http://www.willemboshoff.com/documents/artworks/370-day.htm > for photographs and a more thorough description of the finished sculpture.

[7] Oddly, the artist's website only includes photos of Garden of Words I. To see the most recent manifestation, there are a number of blogs with images; the best, in my opinion, is available at < http://northants.bcss.org.uk/nl182/sa8.htm > .

[8] This final twist, likely not expected nor grasped by the viewer without additional research, is explained as a part of Boshoff's brief artist statement, available at < http://www.willemboshoff.com/documents/artworks/lebab.htm >.

[9] Success stories, attempts to preserve this or that particular tongue, tend to revolve around books. For example, in 1980, Aaron Lansky, realizing the likelihood of Yiddish vanishing, made it his personal mission to collect over 1.5 million Yiddish books, and in 2005, a book, Outwitting History, was published to preserve the story of his preservation of the language.

[10] Script is actually not a direct reflection of a particular spoken language, tending to be far slower to morph than its oral counterpart. In fact, it is this inability for rapid change that allows students today to read Shakespeare's plays with little additional explanation.

[11] Visit the artist's website < http://www.willemboshoff.com/documents/artworks/writing_in_the_sand.htm > for photographs of the completed installation.

[12] Boshoff has never lost his accent, despite his fluency of the English language and frequent interactions with other cultures. Through the wealth of You-tube videos available, truly a valuable resource, the curious Boshoff researcher can familiarize him/herself with the Afrikaans accent while listening to the artist speak eloquently about his work.

[13] He has used the O.E.D. in his artworks as far back as 1990 with his purposefully yet-to-be-completed Blind Alphabet Project—a massive collection of small sculptures expressing various textures, made specifically for the non-sighted to understand how various words might feel.

[14] A compiled dictionary differs from one written completely by the artist in that he keeps the definitions already assigned word for word; his involvement is strictly on the level of selection.

[15] It is also telling that Boshoff proposed the idea for Moonwords to the Mokgalakwena Craft Art Development Foundation as a collaborative piece. He would work together with native craftswomen to construct the chosen Khoisan words through the traditional African art of beading, unified in their efforts to preserve the language. Photographs of Boshoff, the Mokgalakwena craftswomen, and several closeups of the finished beadwork can be viewed on Boshoff's website <http://www.willemboshoff.com/documents/artworks/moonwords.htm>.

Bibliography

Ankerl, Guy. Global Communication Without Universal Civilization. Geneva, Switzerland: INU Press, 2000. Print. INU Societal Research Series.

Auslander, Mark. "Coexistence: Contemporary Cultural Production in South Africa." American Anthropologist 105.3 (2003): pp. 621-623.

Boshoff, Willem. "Willem Boshoff Artist." Artist's Professional Homepage. 2012. Web. <www.willemboshoff.com>.

Brewer, Charlotte. Treasure-House of the Language: The Living OED. New Haven Connecticut; London: Yale University Press, 2007.

Clarkson, Carrol. "Verbal and Visual: The Restless View. Willem Boshoff by Ivan Vladislavić." Scrutiny2: Issues in English Studies in Southern Africa 11.2 (2006): 106-12.

Editing the Image : Strategies in the Production and Reception of the Visual : Including Papers Given at the Thirty-Ninth Annual Conference on Editorial Problems, University of Toronto, 7-8 November 2003. Eds. Mark A. Cheetham, Elizabeth M. Legge, and Catherine M. Soussloff. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008.

Gopnik, Adam. "Faces, Places, Spaces: The Renaissance of Geographic History." The New Yorker, October 29, 2012: A Critic at Large. 1-5.Web.

Graham, Joseph F. Difference in Translation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985.

Harrist, Robert E. The Landscape of Words: Stone Inscriptions from Early and Medieval China. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008.

Hickey, Raymond. Legacies of Colonial English: Studies in Transported Dialects. New York: Cambridge University Press, Oct. 2004.

Higgins, Steven I., et al. "Predicting the Landscape-Scale Distribution of Alien Plants and their Threat to Plant Diversity." Conservation Biology 13.2 (1999): 303-13.

Ho, Ufrieda. "Weapons of a 'Linguistic Terrorist'." The Star: 13. Oct 21, 2011.

Kreamer, Christine Mullen, et al. Inscribing Meaning: Writing and Graphic Systems in African Art. Washington, D.C.; Milan: Smithsonian, National Museum of African Art; 5 Continents, 2007.

McLean, Ian. "On the Edge of Change?: Art, Globalization and Cultural Difference," 2004.

Mitchell, W. J. T. Landscape and Power. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994.

Mosquera, Gerardo. "Alien-Own / Own Alien: Notes on Globalisation and Cultural Difference." Complex Entanglements : Art, Globalisation and Cultural Difference. Ed. Nikos Papastergiadis. Chicago: Rivers Oram Press, 2003. 18-29.

Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, et al. Unpacking Europe: Towards a Critical Reading. Rotterdam, The Netherlands: Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen: NAi Publishers, 2001.

Nagy, Andrea R. "Defining English: Authenticity and Standardization in Seventeenth-Century Dictionaries." Studies in Philology 96.4 (1999): 439-56.

Paton, David Murray. "Willem Boshoff and the Book,"South African Artist's Books and Book-Objects since 1960." MA Fine Arts Department, University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 2000.

Snyman, Johan. "Willem Boshoff's Panifice: Africa and Europe: The Language(s) of Civilization(s)." Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art Fall/Winter 2002.16/17 (2002): 84- 87.

Tuan, Yi-Fu. "Language and the Making of Place: A Narrative-Descriptive Approach." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 81.4 (1991): 684-96. JSTOR. Web. September 10, 2012.

Vladislavić, Ivan, Willem Boshoff, and Philippa Hobbs. Willem Boshoff. 011 Vol. Johannesburg: D. Knut, 2005. Print. TAXI Art Books.