September 30th, 2012

Art as Civil Disobedience

Written by FARRAH KARAPETIAN

In her essay of 1970, Civil Disobedience, Hannah Arendt writes of the difference between shared concerns, which can bind together a group of people with diverse identities, and shared interests, which codify diversity as divisive. For Arendt, a civil disobedient does not operate as an individual; as such, he or she functions and survives only as a member of a group. This is as opposed to the conscientious objector, whose subjective experience of individual conscience distinguishes him or her from the rest of society, “cannot be generalized,” and is therefore “unpolitical.” The civil disobedient may have a conscience, but it is not on behalf of this conscience that he or she acts: it is on behalf of an opinion that that disobedient shares with other disobedients. The opinion does not have to be shared equally or in the same way in order to bind the group together: it is an idea that is considered important to the group, however differently it is considered. What this writing shares with and borrows from Arendt’s argument is the idea that dissent is productive when generalizable, i.e. when its concerns and consequences go beyond the sense of individual internal narrative.

How can the art object foster a political atmosphere of shared concern? On the one hand, imbued with too much intentionality to this end, it can veer too close to “visual rhetoric”, as Ingrid Sischy described Sebastio Salgado’s work in Good Intentions, her essay in the New Yorker in 1991. Irrespective of the problems with respect to Salgado’s work’s display that she points out, such as curatorial strategies that highlight his press clippings, the work itself is “sloppy with symbolism,” with “weighty” subjects “weightily presented” – “complicated mixtures of high aspirations and presumption.” Though some critics disagree with Sischy’s take on the genre of “concerned photography” – notably David Levi Strauss in his essay of the following year, The Documentary Debate: Aesthetic or Anesthetic? – there is for sure a difference between pointing out a problem to a viewer on the one hand and, on the other, leaving room for that viewer to arrive at a sense of conflict for him or herself. Documentary photography can communicate literal events to viewers, sometimes with more compositional integrity and ingenuity than might any other medium, but, as a practice, it lacks a sense of self-regard. No matter how many photographs or pictures are included inside the photographer’s frame, or how many windows or apertures the picture is taken through or of, the documentary photograph rarely seems conscious of its own making. It is an artifact of an event, and sometimes, in being such, communicates a very powerful opinion, but, within its frame, does not admit to being its own creative entity.

Overt consciousness of process is no solution. When a documentary photographer makes an effort to embed a sense of intentionality into his or her photographs, the effort often fails. Luc Delahaye, for example, is a photojournalist who turned into an artist in 2004, after which point he began printing his images of conflict around the world at a scale large enough to feel immersive to a viewer. These photographs often seem as if they would be more effective back in a newspaper; despite the lyricism of the compositions, they do not seem necessarily large. Their scale is not built abstractly into their objecthood, and therefore only seems to assert the situation pictured as being important enough to be big. Although their content suggests issues about which the public should be concerned, the photographer is fantastically detached from these scenes.

This is the traditional perspective of history painting, but such work seems inappropriate in an era recoiling from the monumentality and distance realized by photographs such as those by Andreas Gursky. With global political and economic unrest in the news and a sense that government and financial institutions lack transparency, projects that simply picture disaster, however beautifully – and however large – do not translate to a visual vernacular of any locale.

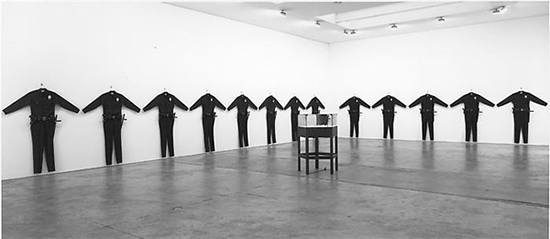

Sometimes the process of translating potent content is what makes an artwork meaningful to a viewing public, especially if that process of translating – any slight shift from the originally observed event or artifact – is available to the viewer. Translation suggests a process of discovery other than that which occurred at an actual event; it suggests that an event has been turned over in an artist’s mind and hand, and that the viewer might likewise spend time with the event. The shifts necessary to suggest translation, however, or the demonstration of having observed and considered something, can be minimal. Andy Warhol’s 1964 screenprint of the Birmingham Race Riot shifts a newspaper photograph only in size and medium from its original form; Vija Celmins’ 1965 painting of a Time Magazine Cover depicting riot scenes similarly changes very little from its mediatic namesake; Glen Ligon’s 1988 painting, “Untitled (I Am A Man)”, of a sign carried at a protest from 1968 inherits that sign’s font, color scheme, shape, and size; and Kelly Walker’s 2006 triptych of silkscreens of police beatings, “Black Star Press”, takes a powerful image, turns it on its side, triplicates it, and subjects it to paint splatters. Chris Burden produced “LAPD Uniform” in 1993, a year after the Los Angeles riots had occurred, and the uniforms, configured to hang on the wall like paper dolls, are just a bit larger than they should be. Each of these artworks take a powerful image from mass media and redoes it, showing just enough evidence of the artist’s process of translation.

Translation can be emphasized through that process of recreation and repetition; it suggests not authoritative authorship, but rather time spent with an idea. Thomas Demand’s Yellowcake photographs of 2007 depict his recreation of his memory of the Nigerian embassy in Rome in which a paper trail regarding the sale of yellowcake uranium by Niger to Iraq was supposed to have been found. Jeff Wall recreated an everyday urban scenario of day laborers standing at a street corner for his photograph of 2006, “Men Waiting.” In “Intervista” (1998), Anri Sala presents his mother with a video of herself, younger, as a communist activist in Albania, and works to retrace her words and to understand them in the context of her present identity. Aernout Mik recreates disasters for his videos, and projects them on sculptural screens, every aspect of his installation a construct of both his experience and its imaginative enactment. In “Reel-Unreel” (2011), Francis Alÿs films children in Kabul, Afghanistan, unspooling a 35 mm film; if at first they are playing with hoops and casually framing army helicopters with their fingers as if filming, soon they are running through the streets in an exercise of duration. They spin film spools we come to believe are copies from films confiscated in an exercise of censorship by the Taliban from the Afghan Film Archive. The children leave trails of movies behind and in front of them. Alÿs is known for videos of durational performances such as these himself, and so the children serve as something of a surrogate, referencing his own process and rendering it meaningful on the level of their experience as children in a country at constant war.

These artworks do not explain themselves, nor do they need to: they suggest and contain the scenarios they stage within themselves and need no further context. They are transparent in their process and reference mediatic realities with which most viewers are literate. They use, in other words, tropes a viewing public is likely to be able to identify and with which that public can develop a sense of shared concern. A transparency of process in an artwork creates a thread a viewer can follow, like that unspooling film, to the end of arriving at that viewer’s own sense of particular concern. In writing, such as that by George Orwell, such threads are self-evident. The writer of Shooting an Elephant does not just note that English colonial rule of Burma is problematic; he discovers how it is so as the story unfolds. The essay begins, “In Moulmein, in lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people – the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me.” It continues, describing Orwell’s experience as a sub-divisional police officer of the town on order to shoot an elephant. He does not describe the Burmese from their point of view, as would someone purporting to be a native speaker, nor from the point of view of an oppressor pitying or siding with the oppressed, as might a public relations officer for an NGO. The writer does not purport objectivity, as might a journalist. Instead, he uses a very detailed account of an event that he found personally uncomfortable to point out what the reader can eventually come to find uncomfortable as well. From the pressure Orwell feels from the expectation of the crowd that follows him, to the endless shots he has to take to move the elephant close to death, to his conclusion that he has shot the elephant to avoid looking a fool, Orwell embarrasses himself on paper, and in doing so, embarrasses his government.

Orwell remains attentive to his process and faithful to the revelation of that process for the reader of his work to follow. He does not transcribe political content in order to broaden – or broadcast – his own sense of concern; he discovers content even as he watches and narrates his own response to circumstance, and his interior monologue is what reveals that response. Those viewing his activity – his performance as a policeman – would have had no idea what he was going through; even Orwell himself, though he experienced the event and set the intention to write the essay, would not have known the extent of what he might reveal until he was done writing. Similarly, with “L.A.P.D. Uniform”, Chris Burden could not have known the effects that would occur with a shift in scale of the uniform and the installation of the uniforms such that they surround their viewers – or not until these shifts were rendered.

The gesture functions like a metaphor enacted, which unfolds its meaning more or less powerfully depending upon the variables at play. Art, then, is certainly a process: an interior process before it is an exterior process, and a transparency of process is key if a reader is to arrive at any sense of consequence of an artwork for him or herself. In the case of “Shooting an Elephant,” process is not revealed through forced familiarity with Orwell’s audience nor through overtly accessible writing or visual evidence of editing; we do not see passages crossed out nor hear intentional vernacular in his word choice. The writer trusts that as he comes to his revelations, so will his readers; he creates in us emotional and political literacy. Not only can we consider his experience step by step, we could try now to examine our experience at the depth he does. He has shown us his steps.

The evidence of Orwell’s process is in the work – not in its background or context, nor even necessarily between this work and another of his works or another work of the same period by another author. It speaks for itself and it is not coy. Of course meaning can be amplified by context and sometimes context is part of a work, but in the cases of Orwell’s essay, Ligon’s sign painting, or Alÿs’ film, for examples, the artwork is enough to create a sense of shared concern and shared process between the writer and reader. We don’t need to read further in order to understand the variables at play. Part of the reason for that is the reliance of these works on narratives that are shared between cultural producers and observers alike: we know the news as much as would a Christian citizen of another generation have known his or her Bible story. This is, in every generation, an inclusive strategy. If a work contains within itself all the information needed to understand it, it is more politically inclusive than a work that requires explanation or prior knowledge. For a work of art to invite a public to a situation of shared concern, it must be legible to that public with or without prior knowledge or insider information.

Vernacular quotations in the election of particular materials is another way of relying on shared narrative, as in Tom Sachs’ use in the 1990s of plywood or cardboard in his sculptures. These materials themselves are part of the vocabulary of any observer. Photographs also serve as a material for such a vocabulary: we all know the postures to which Cindy Sherman’s film stills of the late ‘70s refer, as well as those to which the snapshots from the late ‘90s of Nikki S. Lee refer. We also know what it feels like to take many such a picture, or to be in many such a picture. The trick is, however, not to overuse any one vernacular metaphor: every piece must be a new observation and a new translation. It is lazy for an artist to decide that everything in his or her studio can be made with found lumber or styrofoam because these materials are meaningful on an everyday level; it is lazy to decide that making objects clumsily or as if untrained is a sustainable metaphor, even if doing so once or twice makes a point. The artist must ask him or herself every time a piece is made, “Why this material? Why this handling of the material? Why this time?” This is true even of the election of performance as a “material”; the question of why any particular investigation need be enacted performatively is as crucial a question as is that of physical material. A material and its handling are vehicles for metaphor and the artist must be articulate in his or her choice of vehicle, or the artwork is not worth the effort of expression.

Art, as a process, is a constant call and response: the last piece produced, the last experience observed, the last artwork observed all should be open to revision in the next piece conceived. This is a part of the politics of artmaking, both within one artist’s practice, and between artists’ practices, even generationally. If paintings produced by artists such as Jackson Pollock and Willem De Kooning were understood by a next generation to be motivated by self-expression, that next generation responds: Jasper Johns begins to paint flags, maps, numbers, and targets, and Robert Rauschenberg begin to use found material in his work, both suggesting that their work reveals something other than their selves. Even if some of this trajectory is invented by historians, and even if some of it is untrue, the trajectory itself represents a conversation and a rewriting of the work that comes before, and in that is politics: it is the activity of sharing and revising concerns that motivates the art world from the artist up rather than from the collector down.

One way in which such tendencies are generous is that they keep a transparency of process alive both for a viewing public and for artists of future generations: the sentence of how and why a work of art is made remains legible because of the way it is revised by the artists who come after. Art should never apologize for itself, but it should be open to productive revision. It does happen that artists are asked not to do what they do; it does happen that within the political circumstances of a time and place, a work of art challenges governing tendencies so much that it is whitewashed, figuratively or literally, as the films of Afghanistan apparently challenged the Taliban in 2001, per Francis Alÿs’ narrative in “Reel – Unreel”. The period between the World Wars in Europe saw much such rejection, whether in Hitler’s designation of certain artists as degenerate or in Stalin’s restriction of artistic production to that of the Socialist Realist genre. How quickly a career can turn: Rodchenko spent the mid-1930s making circus paintings, whereas ten and twenty years prior, his striving for objectivity through an emphasis on process and material had rhymed so well with the revolutionary goals of his context.

Censorship can take more subtle forms, however, than pressure from a government, and in today’s global context, in which corporations at times have more influence than countries, a sense of censorship has become more complicated and prevalent than ever. Restriction of expression exists not only in terms of what art is taken down from public view, but what kinds of representations do surround us, and how much – or little – power we feel over our actual and cultural landscapes. Citizens feel an inescapable presence of representations of commerce in the urban scene. Artists sense the commercialization of their museums and the priority of the tastes of board members and collectors over the rule of aesthetic or conceptual movement. It can be the instinct of artists to try to defy commodification, and this effort is often the subject of conversation; it often informs the material or immaterial choices artists make. The effort, though, is futile; any thing and any action can be sold, as long as the currency in question is money. This is only a shameful thing if it overmuch influences the work. When the products of individual art stars are branded, marketed, and valued regardless of the way in which their work responds to or creates response within their environment, we have a system defined by dealers. When artists motivate one another, however, through responsiveness to their cultural circumstance and to one another’s work, they define cultural capital. In their responsiveness, they exchange this capital, and it is this exchange that makes the movements of which our art world and our global culture feels deprived. Private institutions will always find ways to privilege certain practices at certain times; the power balance is upset by idiosyncrasy in artmaking, not, eventually, in personality. An artwork is the setting for the discovery and sharing of concerns; insofar as it revises collective experience via individual intention, it is always already an act of civil disobedience.

Farrah Karapetian is an artist, writer and lecturer based in Los Angeles.