From “Eremitic” artist residency to “Heterotopia”: shifts in the cultural politics of Villa Romana (1905-2017)

Written by Carlotta Castellani

With its program of talks, symposiums and exhibitions, the artist residency Villa Romana currently promotes a perpetual interaction between cultures and creates cross-cultural links for a mutual understanding through art. In this sense, the house is a unique place in the context of Florence (ill.1).

Going back in history, it is clear that Villa Romana has been a singular institution since 1905, when it was first opened as a German artist residency in Florence thanks to the painter Max Klinger (1857-1920) and with the help of the Deutscher Künstlerbund (German Artists' Association) (ill.2). Created by artists for artists, since then Villa Romana has represented an independent forum and was a counter-model to other German prizes awarded to artists. Villa Romana hosts each year four fellow artists, who are staying in the house for ten months. With the support of private sponsors, Villa Romana has stated in its statute that every fellow artist must be selected by a specific jury made up of other artists. This self-sufficient organization has assured the residency its flexible nature. Over the years, the life in the residency and its cultural program of activities has changed substantially. Faced with the upheaval that had taken place in the contemporary art world, Villa Romana experienced two significant shifts thanks to the foresight of its last director Joachim Burmeister (1972-2005) and its current director Angelika Stepken (2006-2017) who have been the promoters of innovative initiatives to ensure a proper renewal of the house.

After the disastrous flood in 1966 and the consequent conservative local cultural policy[1], Florence did not look like a city open to contemporary art when compared to other cities (Paris, London, New York): many German artists questioned the legitimacy of the Villa Romana Award in this particular urban context. To renew the role of the Villa, Joachim Burmeister, elected director in March 1972, understood that it was necessary to establish direct contacts with Germany in the arts sector. Besides the four artists awarded each year, he offered an apartment-atelier for several months to up to nine guest artists, inviting also many people connected to the art world, such as gallery owners, museum directors, curators and journalists[2]. Some of these guests wrote encomiastic articles on the Villa that fostered the development of that network of guests desired by Burmeister. As an early consequence, a more heterogeneous selection of artists began to accept the fellowship amongst which were Dorothee von Windheim (1975 award), Michael Buthe (1976 award), Nikolaus Lang (1976 award) and Anna Oppermann (1977 award). They all contributed to the fundamental shift of perspective on Florence, as can be seen in their own words or works. Michael Buthe describes the Piazza Santo Spirito in Florence as similar to Jemaa el Fna, the major square in Marrakesh. Anna Oppermann integrates fragments of the city - from tomatoes to postcards - into her work. Martin Kippenberger, who was not an awarded artist but a guest at Villa Romana, used those same fragments as subjects of his small oil canvases entitled Noi tedeschi a Firenze, all realized at the bar in front of Palazzo Pitti.

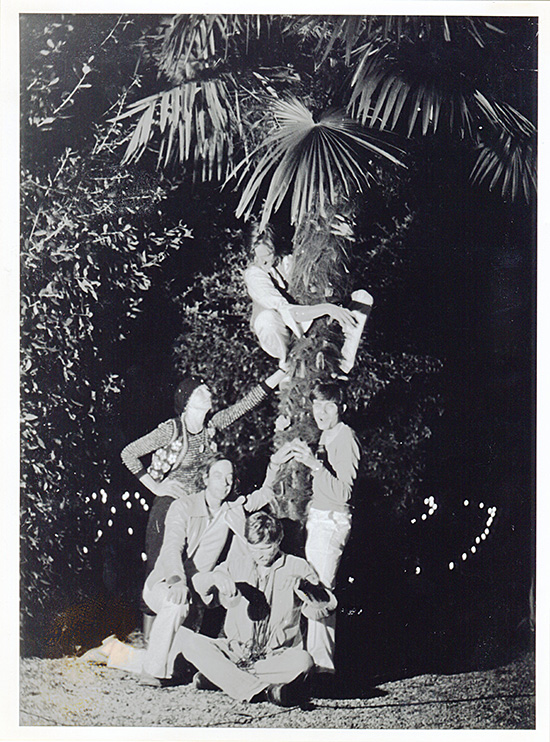

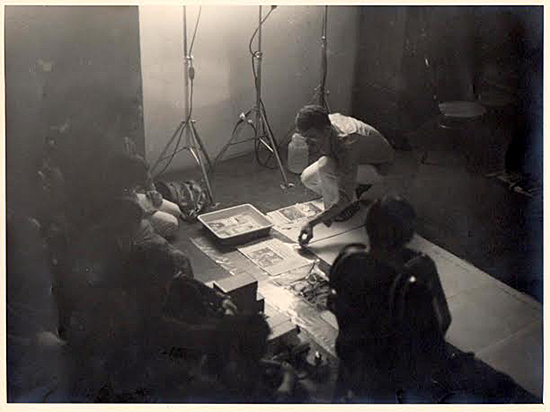

These artists split the heavy heritage of Florence into fragments to remove the idea of the city as the birthplace of the Renaissance, because a new sense of plurality of cultures collided with the tyrannic monolith of Renaissance Art. As Bazon Brock, often guest of the Villa since 1974, wrote in 1980: “the function of the new, in the present, consists of being able to take possession of the old […]. The avant-garde is only that which makes us look at apparently consolidated entities of tradition in a new way, that is it makes us establish new traditions[3]”. At the end of July 1977, the previously mentioned residents organized an evening of performances around the garden entitled Künstler arbeiten für Künstler [Artists working for artists](ill. 3) which indicated the Villa’s transformation from an eremitic Nazarene-like place to a laboratory of production and hybridization of the arts. In order to transform the Villa into a “laboratory of material production of visual arts, in which it may be possible to compare antithetical positions, approach the Italian avant-garde and correct the sentimental vision of Italy[4]”, Burmeister also increased the contacts and collaboration with local groups of experimental artists[5] such as the gallery Schema, the video art production studio Art/tapes/22 and the artist run space Zona-no-Profit. In 1978, events dedicated to these artists also began to be presented in Villa Romana such as the performance of Lanfranco Baldi Mio caro demonio (ill. 4).

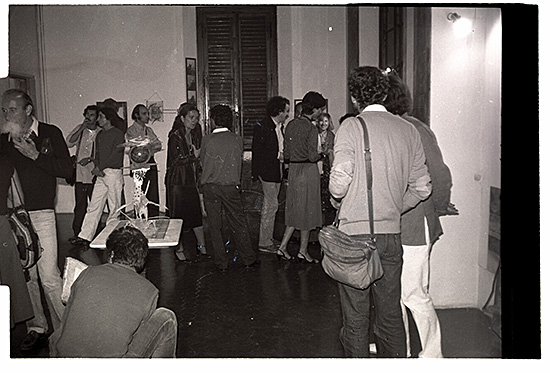

Following the success of these collaborations, which manifested the potential of synergic projects between the artist residency and Florence, Burmeister proceeded with a programme of continuous shows inside the rooms of the Villa. The exhibition space Salone Villa Romana opened in 1979 and its direction was entrusted to Katalin Burmeister. Between 1979 and 2004 more than eighty exhibitions were hosted there, dedicated to Italian and international artists such as Luciano Bartolini, Michael Buthe, Anne and Patrick Poirier, Marco Gastini, Georg Baselitz, Mimmo Paladino, Mario Nigro and with important guest artists like Ulay and Marina Abramović[6]. Since then, Villa Romana has been an integral part of the cultural life of the city (ill.5).

The concept of having a continuous public program of exhibitions inside the house and inviting a large number of guest artists each year has continued and is still active today. Nevertheless, as we entered the new millennium with increased globalization and shifting geopolitics, Villa Romana needed a new transformation as an artist residency. Angelika Stepken, a professional curator who was nominated as the director in 2006, changed the way the residency is organized by pursuing the goal of working on a transnational level. As she says in a recent interview : “As a freelance curator I have worked transnationally by organizing exhibitions in China, India, Turkey and Scandinavia. I have always been interested in the reality of the ´other` and in the use of geography as an instrument to change perspectives. This is why I was so interested in working for an artist residency located in Italy[7]”. Stepken considered the artist residency as a place beyond all places, a ´heterotopia` to use Michel Foucault’s words, and the fact that it was located in Florence did not worry her: “Like any place, this location has its limits and its potentialities”, she says. Since her arrival in Florence, the new director has dismantled the idea of Villa Romana as a bi-national platform – Italian and German – still dominant in the previous decades. In her opinion “the artist's residencies guarantee artists to ´be elsewhere`, to change perspective, which is a fundamental experience: not only outside your daily life, but also dealing with other realities, other stories. It is good, it is a necessity in a globalized world.” Favoring quality parameters, Villa Romana awards currently the most promising emerging artists based in Germany, whether they were born or not in the country. “Compared with the past”, Stepken explains, “the change of the contemporary art world in a globalized world implicated a change in the number of German artists actually selected every year in Villa Romana. Everyone knows that this is a German institute and we still host many German artists, but what we offer is a transnational platform, which does not insist on the concept of German nationality anymore[8]. Now it is said in Germany that the foreign cultural policy has to transcend nationalism and it has to be exposed to the ´unknown`, to the ´other`, in order to clarify its perception. It is a very recent change of perspective. In my case, I've always worked in this way…” This aspect of the contemporary art world can be seen, for example, in a city like Berlin where more than 9,000 artists from all over the world live today, or in the field of contemporary art history, not anymore ruled by national and linguistic schools but instead oriented to a world art history. Moreover, in these uncertain times of political mistrust between nations, a special geographical emphasis has been given to the cultures of the "non-aligned" countries of the Mediterranean area[9].

The guest artists invited to Florence come from these areas: Syria, Kosovo, Israel, Lebanon, Egypt, Morocco, Albania, etc[10]. “Since 2007”, Stepken explains, “we have had the practice of inviting artists from the Mediterranean area. Of course, after the Arab Spring in 2011, this propensity of Villa Romana has been much more echoed”. Focusing on the very real problem of immigration, in 2011 in Villa Romana was organized the exhibition Lampedusa. The Day After. Visuelle Perspektiven (ill. 6), curated by Maurizio Bortolotti, which showed a rich choice of photo and video archives to afford an understanding of the phenomenon of immigration. A more recent example of this practice is the exhibition project Disappearances. Appearances. Publishing (2017, ill. 7) by the artist collective Fehras Publishing Practices (Kenan Darwich, Omar Nicolas, Sami Rustom), which showed some reflections on the private library of the Arabic novelist Abd Al-Rahman Munif and rereads its holdings providing insights into the long history of production by publishers in the Arab world since the 40’s.

Following Michel Foucault’s concept of space, it can be said that any site is defined by a set of relations. In Villa Romana these relations are always unexpected “capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible. (…) a whole series of places that are foreign to one another[11]”. This is the keyword in understanding the cultural politics in the house today, a “relation spoken multilingually[12]”, where it is possible to break down certain oppositions “between private space and public space, between family space and social space, between cultural space and useful space, between the space of leisure and that of work[13]”. Relation, connectivity and understanding of the otherness are for any artist the most common concerns today because they are the substance of contemporary being. Each artist awarded may contribute to this program of exchanges by inviting other artists as guests in the Villa. Nevertheless, inside the house reigns the “right of opacity” as defined by Édouard Glissant[14]. As Stepken explains, “the contacts between people here flow smoothly, without inserting them into a vision of the pre-established relationships. Opacity is a moment inside the home, it is the most important aspect of the home. Everyone finds his or her space and offers something in common. Everyone is free to decide how to participate. The only obligation is the respect of coexistence, the common desire for peace. The real gift we offer to artists is « time », time in a peaceful place surrounded by a garden (ill. 8) and intimacy. It is the most important factor for the quality of their work here. This intimacy is a huge value for art today and is a very fragile aspect of their practice that they can cultivate here». In this sense, the Villa is a system of opening and closing that both isolates and makes it penetrable[15].

With full respect for this intimacy, Villa Romana provides links between people and brings cultural activities together through performances, exhibitions, symposiums and by promoting collaboration between guests. In this sense, for a city like Florence, Villa Romana is an important hub for Contemporary Art: it is a communication platform, continually changing, characterized by a discomforting pluralism that brings new narratives into existence and poses difficult or unexpected questions with the help of fresh perspectives. Displaying the results of these interdisciplinary narratives inside the magnificent halls of the Villa adds a post-colonial and trans-local approach to contemporary art. This approach underlines the actual and possible connections between distance and locality developing innovative relationships between artists and audiences. Many workshops organized in the house deal with cultural diversity, trying to connect people through art making. The Dat filmmaking workshop, organized by the filmmaker Fide Dayo, offered the chance to learn how to develop a story for the screen with a focus on Black History in Italy and Communities of African Descent in the city of Florence. The workshop The Flying Carpet instead, organized by the Iranian artist Farkhondeh Shahroudi in collaboration with PACI - a center for refugees and asylum seekers - brings together people from different cultures through a common artistic project: the production of a gigantic Flying Carpet (ill. 9). The choice of the carpet has to do with its meaning in Eastern traditions as a “garden (…) a sacred space that was supposed to bring together inside its rectangle four parts representing the four parts of the world, with a space still more sacred than the others[16]”.

The interest for transnational perspectives goes in parallel with the focus on the peculiarities of the local contemporary culture. Creative collaboration extends to local partners, including artists, students and cultural organizations based in Florence or in Tuscany.

Since 2011, Villa Romana has been home to the non-profit cultural association Radio Papesse, curated by Ilaria Gadenz and Carola Haupt (ill. 10): a web radio dedicated to the sonic dimension of contemporary art and culture, an open archive for sound art, interviews, documentaries and music. With this independent radio Villa Romana has collaborated on many projects like Nuovi Paesaggi (2012), a residency program for sound artists and Süden Radio (2013 - 2017), an investigation of the new geographies of sound. Many of the exhibitions held in Villa Romana are focused on contemporary artists based in Tuscany, from the past and from the present, like SuperStudio, Ketty La Rocca, Renato Ranaldi, Giuseppe Chiari (in collaboration with Radio Papesse), Andrea d’Amore, Leone Contini, and Kinkaleri. To arrive at a sort of absolute overturning of the traditional history of Florence, part of Stepken’s curatorial practice is devoted to changing the perspective of the narrative of the city as an icon of the Renaissance. Recent projects allow for the deconstructing of the image of the city as a center of the canonizing understanding of culture. In 2013 four artists – Mariechen Danz, Genghis Khan Fabrication Co., Liz Glynn, Johannes Paul Raether (ill.11)-- focused their works on the concept of Renaissance resistance and in 2015 it was organized the symposium Unmapping the Renaissance in collaboration with the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence that focused on a new sense of fragmented history and problematic legacy of Renaissance Art (ill.12).

Next year, projects will go even further in this expanded geography: with the help of the curator Nick Murphy, between Italy and Senegal 14 artists from different nationalities will develop their personal narrative on the problem of immigration from these different perspectives : « I would also like to include the reality of immigrants in Tuscany who are more than 20,000 and have a cultural reality that we do not perceive. We will dedicate a year round project to this. It will be completely focused on research. There is already a team working on this theme here in Florence, with which we will develop a continuous communication system. And in the spring of 2019 there will be an exhibition and a book on the project… »

Carlotta Castellani is an art historian and archivist based in Florence. In 2016

she received her Ph.D. in Art History, Literature and Cultural Studies at the

University of Florence and Paris IV Sorbonne. Since 2014, she has been

responsible for the reordering and inventory of the historical Archive of Villa Romana

in Florence with a research project entitled: “Inventing the archive: Development of a

digital archive on the exhibition history of Villa Romana” (See C. Castellani, Der

Salone Villa Romana. Ein internationaler Ausstellungsraum im Florenz der 80er Jahre.

Rekonstruktion eines Archivs 1979-2004, Gli Ori, 2017). From 2009 to 2017 she has

been the scientific assistant of Max Seidel at the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florenz –

Max-Planck-Institut. Her writings have been published in books, exhibition catalogues,

national and international journals.

NOTES

[1] The art critic Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti in 1966 addressed an open call to the most interesting Italian artists, asking them to produce an artwork and donate it to the city. This call had an overwhelming response, but then Ragghainti’s collection did not find an appropriate exhibition space in Florence.

[2] Including Bazon Brock (one of the organisers of Documenta) , Peter Winter (“F.A.Z.” and “Kunstwerk”), Willi Bongard (“Art Aktuell”) and Dietrich Helms (Documenta 5 and “F.A.Z.”)

[3] B. Brock, Avanguardia è solo quel che ci porta a instaurare nuove tradizioni. Sulla questione del progresso nelle arti (estratto), in O sole mio oder Sichselbst begreifen: Kennst du das Land wo die Zitronen blühm, edited by H. Berendt and W. Woessner, Coop. Officine grafiche, Firenze 1980, p. 94.

[4] J. Burmeister, untitled, in Fussmann, Gutbub, Kaminski, Maier-Aichen. Villa Romana 1972, Tipografia Giuntina, Florence 1972, no page number.

[5] P.L. Tazzi, Pittura/Materiale, in id. (curated by), Pittura/Materiale Paolo Masi, Lanfranco Baldi, Luciano Bartolini, Lucio Pozzi, Richard Tuttle, Emanuele Becheri, Filippo Manzini, Centro d’Arte Spaziotempo, Florence 2007, p. 10.

[6] On this exhibition place, see C. Castellani, Il Salone Villa Romana: uno spazio espositivo internazionale nella Firenze degli anni Ottanta. Ricostruzione di un archivio (1979-2004), Pistoia, Gli Ori, 2017 (on print).

[7] Angelika Stepken in a conversation with Carlotta Castellani, Florence, 20th August 2017.

[8] We can mention, for example, Farkhondeh Shahroudi (2017) born 1962 in Tehran, who found asylum in Germany in the 1990s after protests against the Shah regime, Flaka Haliti (2015) born 1982 in Prishtina (Kosovo), Petrit Halilaj (2014) born in 1986 in Kostërrc (Kosovo) who lives and works in Munich and Alvaro Urbano born in 1983 in Madrid, who lives and works in Berlin.

[9] See On One Side of the Same Water. Artistic Practice between Tirana and Tangier, Edited by Angelika Stepken. Text by Mirene Arsanios, Roy Brand, Hassan Khan, Sarah Rifky, Angelika Stepken, Despina Zeykili, et al., Hatje Cantz 2012.

[10]2017: Bassel Al Saadi (Damascus); Faton Mazreku (Malishevë, Kosovo); Fehras Publishing Practices (Damascus/Berlin); 2016: Rula Ali, (Qamishly/Berlin) Hagar Masoud (Cairo/Paris); Ada Karczmarczyk, (Warsaw); Natalia Ali (Damascus/Berlin); 2015: Zineb Andress Arraki, Casablanca; Dalia Boukhari, Ramallah; Karolina Bregula, Warsaw; Alaa Ghosheh, Jerusalem; 2014: Ghassan Halwani, Beirut; Soudade Kaadan, Beirut; 2013: Honza Zamojski, Posen; Sofiane Zouggar, Khemis Miliana; 2012: Eman Hamdy, Alexandria; Karim Rafi, Casablanca; Enkelejd Zonja, Tirana; 2011: Mirene Arsanios, Beirut; Eleni Kamma, Brussels and Maastricht Setareh Shahbazi, Beirut and Berlin; 2010: Bahman Jalali, Teheran, Rana Javadi, Teheran, Eleni Kamma, Brussels and Maastricht, Diana Machulina, Moskau, Anna Molska, Warsaw; 2009: Erik Göngrich, Berlin; Wafa Hourani, Ramallah, Hany Rashed, Cairo, Ines Schaber, Berlin; 2008: Vladena Gromova, Petrozavodsk; Aglaia Konrad, Brussels; Karen Sargsyan, Amsterdam; 2007: Edi Hila, Tirana.

[11] M. Foucault, Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, in: “Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité”, October, 1984, p. 6.

[12] É. Glissant, Poetics of relation, University of Michigan Press, 2010, pp. 18-19.

[13] M. Foucault, Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, p. 1.

[14] É. Glissant, Poetics of relation, pp. 18-19.

[15] M. Foucault, Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, p. 7.

[16] M. Foucault, Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias, cit., p. 6.