October 8, 2015

Reconsidering the Responsibility of an Artist in the Postcolonial Buddhist Society of Sri Lanka

Written by Sabine Grosser

In the 1990s in Sri Lanka a new generation emerged that was discussing the responsibility of an artist in a changing society and which gradually redefined the concepts of the local art scene. The new artists experimented with new art forms in the local context and cooperated with various social groups trying to influence the public opinion and working for a peaceful solution to the ongoing conflict in the country.

In Germany at least, the popularity of our conference subject and the main theme of this issue of Seismopolite - the question of social responsibility in art - follows an undulating curve. This became even more clear to me in 1997, in what felt like a downward period for activist art in my home country - yet also the same year that I travelled for the first time to Sri Lanka, where the responsibility of an artist in society happened to be one of the major topics of the art scene. Working as a DAAD Senior Lecturer at the University of Kelaniya between 1997 and 2002 I had the chance to become an eye witness to the development of this vibrant art scene. I collected material, designed a research concept and started to write about the ongoing developments.[1]

The new generation of artists that developed nearly half a century after the colonial regime, defines itself in context of a complex, changing and multifaceted culture and rooting in a strong Buddhist tradition.

Until the end of colonialism current social and political topics hardly played a major role in the pictures of Sri Lankan art. During the 90s the ongoing civil war in Sri Lanka (1983 – 2009) - its impact on society and the question of the responsibility of an artist, as well the impacts of globalization - were the dominating topics in the local art scene. The children of the new middle class in this post-colonial society felt an obligation to shape the future society.[2] Artists like Chandraguptha Thenuwara[3] and Jagath Weerasinghe express this obligation very clearly both through their art and words.

Jagath Weerasinghe is the senior of this artist generation, not only with respect to age (born in 1954) and reverence, but also considering his role as a catalyst for the development of the new artist generation in the 90s. After studying in the USA he came back to his country in 1992 taking a new perspective on his surroundings. The main motivation for him is his personal experience as an individual confronted by a complex and complicated social, political and economic surrounding.

E.g. in the drawing “Long Necked Man” from 1992, which he worked on shortly after returning to Sri Lanka, Jagath Weerasinghe depicts himself as a naked man, with a deformed, overlong neck, restrained within the frames of his surroundings that are also the constraints of the picture. In the interview he describes his situation as highly influenced by the Buddhist traditions and destabilized by the postcolonial context as well as the long lasting political violence in Sri Lanka. Among other things, he was appalled by the attitude of the Buddhist clergy that supported the ongoing civil war – contrary to the Buddhist philosophy. In his paintings he combines his examination of the virulent topic of war and violence in his country with his personal positioning as a Buddhist.

He addresses this topic in the early painting “Broken Stupa” (1992), which shows a scattered stupa; a prominent symbol for Buddhist culture in Sri Lanka. The stupa – originating from India – developed its specific form (in the shape of a bell) in Sri Lanka and is understood as a core part of the local temple architecture. The stupa represents the cosmos and the Nirvana. Through both these paintings Jagath Weerasinghe formally opposes postulates of the local modernism he experienced during his education, mainly in Sri Lanka; e.g. the “perfect composition” or the attempt to depict any kind of reality. Those ideas did not correspond with his experience of a fragile, unclear and fragmented surrounding. In the interview he states:

And why do I think that I can make a perfect painting when everything else in the world is totally screwed up and collapsed… (Interview with Jagath Weerasinghe 2002, printed in Grosser 2010, 516 – 532)

Weerasinghe thus distinguishes his own approach explicitly from the local reception of the Western concept of Modernism. Not only does he oppose the idea of a perfect composition, as in the painting of the broken stupa; he also uses muddy, dirty colours, in contrast to the bright colours of Buddhism.

However, he is not only introducing new topics and new artistic techniques into the art scene, but also constructs a new role model of the artist in the local context and tries to gain influence on society and its development in various ways, describing his role as an artist in society on multiple levels:

First as an activist in art and politics, second as a teacher and third as an artist. These roles mix together, boundaries are blurred. (Grosser 2010)

Two groundbreaking installations, Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s “Barrelism“ and Jagath Weerasinghe’s “Yantra Gala and the Round Pilgrimage“ both reflect on the artist’s role in society. In the latter work, which was exhibited at the Heritage Gallery – an experimental exhibition space initiated by a local architect and managed by Nepalese artist and graphic designer Balbier Bodth – Jagath Weerasinghe refers to his Buddhist background and combines artistic, political and spiritual aspects. He thus describes how the idea for “Yantra Gala and the Round Pilgrimage“ initially occurred in his mind:

… organizing a ceremony for a group of parents, whose children had disappeared and been murdered in 1989-90 at torture camps at Embilipitiya. … most of the mothers came wearing white saris and holding a picture of their lost child. These women reminded me of mothers going to temples with flowers, held in their hands. Their white saris made it so severe a feeling. Instead of flowers, now they are carrying the photograph of a child who is now murdered. The irony in this situation sank deep into my heart. What made them go from place to place in search of their lost children, as if they were doing the annual round pilgrimage of sacred places? One of the mothers asked me crying, `Is nobody concerned with our suffering?' My work began from this question.

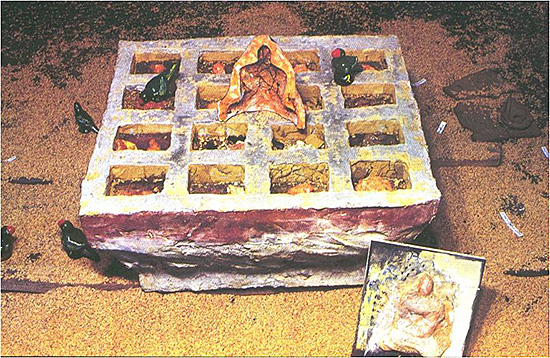

The exhibition consists of different components: The Yantra Gala (91.4 x 91.4 x 61 cm), a relief titled “Altar Piece” (182 x 46 x 12 cm) and eight paintings (each 86.4 x 55.9 cm). The Yantra Gala in the centre of the room is empty, only the mould reminds of its intentional function as base of a Buddha statue. Jagath Weerasinghe understands the inoperable Yantra Gala as a metaphor of the lost Buddhist Dharma and a symbol for a sacred Buddhist place. Around the stone rice is spread on the ground, reminding us of everyday scenes of drying rice on the street. In between the crops small labels with names of torture and detention camps, as well as names of sacred places in Sri Lanka can be detected. Small green birds made out of clay are distributed all over the room, like small symbols of hope. On the central wall the “Altar Piece” – a relief with another small mould of a Buddha statue and scattered clay flowers and lamps framed by two paintings of a “Mal Asabaya” – evoke impressions of an altar, which has lost its function.

The eight small paintings show a variation of similar scenes in dark colours highlighted with clear yellow colour: Women in Saris, holding a picture in their hands, an empty speech balloon symbolising their unheard voices and maps of Sri Lanka representing the search of the mothers for their lost children. With the combination of the different components the artist sets an analogy between the search of the mothers and the annual round pilgrimage combining twelve sacred places on the island.

The symbol of the “Barrel” is connected with the personal experiences of the artist. As a child living in the eastern province he saw burning barrels alongside the road used by workers building streets, promising the opportunity to meet friends and relatives more easily and to get connected with the world. During the civil war this positive symbolic meaning changed: In Colombo the barrels painted in camouflage colours and installed as checkpoints became part of the urban landscape, disturbing the accessibility of places, limiting the freedom of movement.

With time the artist became more interested in the barrel as an object, its objecthood and locality, using the cylindrical container with a height of 35' and a diameter of 23' in his artwork in a newly defined context of his paintings, drawings and installations and as a symbol for the barricades in the roads of Colombo during the civil war. In the interview he describes his association of the barrels with vessels that hold the blood of people.

As an art object in a newly defined context the barrel provokes discussions about the histories, geographies, localities of militarization and networking of hegemonic and militarized political power. Thenuwara also uses the power and the infrastructure of the art world very consciously – like the secure and semi-public surrounding of the gallery space in his first installation of “Barrelism” at the Heritage Gallery – to establish the idea of his Barrelism. As plans for his first public installation of the “Monument for the Innocent Victims of War” in front of the Galadari Hotel in Colombo were disturbed by a bomb blast there – Thenuwara used the open space in front of the Vibhavi Art Academy for the installation – opposing the bureaucratic state power, instead.

The two mentioned exhibitions intensified the public discussion about art’s social responsability; more and more artists raised their voice, like Anoli Perera, Kingsley Gunatillake, Tissa de Alwis or Muhanned Cader – to introduce some more names. Formally and with respect to the content they go beyond the limitations of the easel painting and contribute to a public process of opinion making against the war.

A younger artist like Pradeep Chandrasiri, born in 1968 and himself a victim of a torture camp, connects to the local visual context with his installation “Broken Hands”: He uses the very common clay as material for the hands lying on wooden piles in different heights. In combination with charcoal, oil lamps and beetle leaves he evokes impressions of local everyday culture which is not only limited to temples or museums.

In his artwork, Sujith Rathnayake, born 1971 in Ranna, refers to the aesthetics of the local print media of the time: The general representation of the war is dominated by pictures of scattered body parts of the suicide bombers depicted in the local press without restrictions. Rathnayake uses these pictures in his artwork and combines them with his own gestural paintings[4]

At the turn of the centuries the artists also focused on developing new systems of distribution for their art: Public space and mobile concepts for exhibiting art play an increasingly important role, like e.g. the concept of a mobile exhibition of flags “Artists Against War: Flag-Project-Workshop“ (“Noothana Sithuvam Vansaya“) designed by Sri Lankan artists and presented at various public places of political interest.

Within this process new concepts of commemoration in public space are also introduced on the island. Already during the ongoing conflict two memorials are inaugurated: “The Shrine of Innocents” (1999) by Jagath Weerasinghe close to the parliament lake and Chandraguptha Thenuwara’s “The Monument of the Disappeared” (2000) in Raddulowa. Both memorials have very different concepts and stories. In a separate passage in my book I outline the different concepts and the development of those places. Both are dedicated to all victims of the lasting conflict. But the first is very much involved in local power plays. The latter one is more dedicated to grass root structures in a global context and uses transnational networks. In 2015, while the “Shrine of Innocents” has been abandoned, the “Monument of the Disappeared” is still involved in regular official commemoration ceremonies.

Sabine Grosser is Professor of Aesthetic Learning at the University of Applied Science, Kiel, and author of Kunst und Erinnerungskultur Sri Lankas im Kontext kultureller Globalisierung – Eine multiperspektivische Betrachtung als Beitrag zum transkulturellen Dialog, Oberhausen 2010.

[1] In 2010 I structured my readings in a publication about contemporary art and the culture of commemoration in Sri Lanka and especially its developments at the turn of the centuries. The result was published in German language (post doctoral thesis): Sabine Grosser, Kunst und Erinnerungskultur Sri Lankas im Kontext kultureller Globalisierung–Eine multiperspektivische Betrachtung als Beitrag zum transkulturellen Dialog (Oberhausen 2010). In my writings I develop a multi-perspective approach to contemporary art in Sri Lanka and especially its developments at the turn of the centuries. Included in the book are topic-centred-interviews with five artists: two female, Anoli Perera and Druvinka Madawela and three male; Koralegadara Pushpakumar, Chandraguptha Thenuwara and Jagath Weerashinghe.

[2] This is evident in all artist interviews (taken in 2002) done as part of my research, and that can be accessed in the book.

[3] See my article, “At the Turn of the Centuries: Art and Politics in Sri Lanka” (2014) for a further description of Thenuwara’s work in this context.

[4] See also Grosser 2014.

Bibliography

Grosser, Sabine: Kunst und Erinnerungskultur Sri Lankas im Kontext kultureller Globalisierung – Eine multiperspektivische Betrachtung als Beitrag zum transkulturellen Dialog, Oberhausen 2010.

- "At the Turn of the Centuries: Art and Politics in Sri Lanka". Seismopolite issue 9, 2014.