December 29, 2015

So we may understand one another

A Travelogue

Written by Bharti Lalwani

"Je mehr ein Mensch bereit ist, im Fremden den Feind zu sehen, umso weniger kennt er sich selber."

"The more a person is willing to see the stranger as the enemy, the less he knows himself."

- Dr. Erwin Ringel, Austrian Psychiatrist, Social Critic and Author of The Austrian Soul (1921-1994)

My selection as the founding-resident at the first and perhaps the only Residency in the world offered exclusively to an art critic rather than a curator-writer-artist, came about as a result of a novel partnership between the Austrian chapter of Association of International Art Critics (AICA) and Kunsthaus Wien, a museum dedicated to Viennese artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser (1928-2000). Nestled on top of the museum was the radical artist's home that was to be my residence for four weeks. Within was an unusual experience of uneven floors and an abounding terrace garden where robust trees bore apples, pears, plums and chestnuts, and a small patch in the garden's far corner yielded bountiful harvests of heirloom tomatoes.

AICA-Kunsthaus Wien Critic Residency is an initiative proposed by AICA President Sabine Vogel to nurture not a curator or an artist but an Art Critic who served no commercial interests. Experimental in nature, no impositions were to be made on me while I resided in Hundertwasser's home. How I chose to spend my time during the month would be up to my discretion. This is unlike curatorial, artist or writer residencies where an exhibition proposal, new artwork, or some form of tangible outcome is immediately expected. The only condition expressed was that I share my knowledge and research through an informal talk upon my arrival and discuss my experiences in Austria before I left. Being the first meant a responsibility towards building the Residency as a valuable point of exchange, to illustrate what could be accomplished - to plant a seedling in Hundertwasser's garden if you will.

In order to share knowledge gathered in my six years as a critic, I chose to forgo the requested informal 15-minute format, instead preparing a lecture on Southeast Asian history and contemporary art. As I spoke about art practices that I had reviewed within historical and political context of at least six SEA countries to a select audience of Vienna’s critics, curators, artists and museum representatives, the lecture was an opportunity to put my own knowledge to test. I also expected this talk to open up avenues for discussing art and history of Austria within the wider context of Europe, to spark conversations with new friends and to be challenged by would-be skeptics.

Southeast Asia’s history of cosmopolitanism, richly intermingling cultural and religious practices, social systems, hybrid artistic styles and languages, all evidence a global and inclusive outlook. Such textured synthesis, the result of exchanges established through maritime trade and migration assured an influx of goods and ideas. The blending of old and new, local and foreign made apparent many direct and indirect connections between regions, countries and traditions thereby dismissing populist rhetoric that entertain any notion of ‘pure’ racial heritage. Such a rational scrutiny of history especially defies chauvinist interpretations of culture, religion and tradition in today’s climate of xenophobia and fundamentalism permeating the globe. By examining contemporary art practices of Southeast Asian artists across three generations, I have found that many employed art as a medium to critique moral assumptions, corruption, repression, social inequality, totalitarianism, political power and its connection with religious fanaticism and superstitious practices. History too has been relentlessly investigated by SEA artists who illuminate its dark half-forgotten chapters in order to contest contemporary mainstream conjectures and prejudice. These are concepts that transcend their specific local circumstances to universal appeal. The visual prompts within the art - I emphasized to the select audience in Vienna this past August - should indeed be legible to those unfamiliar with Southeast Asian countries, one should be able to unlock philosophical questioning embedded in the conceptual-core of particular artworks. That art could be a potent medium through which to advocate tolerance and reason within a diverse society is the sort of idealism that I take seriously as a critic. Relinquishing such idealism (not the same as naiveté) would mean existing in a state of despair or worse, cynicism.

By the time I arrived in Vienna, the Greek financial crisis reached its height with social tension and political polarization. However, barely into my first week, conversations switched to focus on a greater humanitarian crisis as scores of people made their way to the EU as refugees mainly from Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan and Somalia, among other destabilized countries. Harrowing reports kept emerging almost daily of babies, children, women and men who did not survive their treacherous journeys over sea and land; of how these helpless migrants were being treated at refugee camps in Hungary; and of the anxiety and fear felt by the European Union at the inevitability of accepting a vast influx of migrants at once. At the nucleus of this anxiety was an element of creeping paranoia and fascism. Some saw these refugees as brown Muslim men bearing cell phones, automatically assumed to be linked to terrorist-group ISIS. They were here, apparently, to eviscerate the European 'way of life'.

Thankfully, countering this fascist xenophobic fringe were numerous voices of sanity campaigning through social media and public spaces for compassion and solidarity. On the night of 31st August 2015, around 20,000 people in Vienna took to the streets to have their voices heard in favour of welcoming those displaced. This came just days after the shocking discovery of 71 migrants found dead in a truck abandoned on a main Austrian highway. Critical news outlets urged citizens to consider the cause and consequences of foreign policies over the last decades while recalling how Austria has accepted refugees in 1956, when the Soviet Union encroached upon Hungary, followed by ‘Prague Spring’ of 1968 when Czechoslovakians fled to Austria with the same influx between 1981-82. Going further back in history, critics detailed how social change and industrialization under the 19th century Habsburg Empire brought together people of Czech, Polish, Hungarian, Slovenian, Serbian, and Croatian origin. By all means, Europe had been a melting pot, at once multicultural and multilingual.

Given the opportunity to explore Austria through this Residency, I wondered if I could make sense of the country through its contemporary art. Among my first visits was the Museum Moderner Kunst - Foundation Ludwig Vienna (Mumok) at the Museums Quartier where I met Susanne Neuburger, Collections Head of Mumok and Curator of the blockbuster exhibition Ludwig Goes Pop. As I introduced myself and elaborated on my work within the Asian context, speaking generously of artists of Vietnam, Thailand and so on, Neuburger interjected to admit to “blind spots” within the museum's collection. According to her, there was little context, or need, or funding to connect beyond Europe and America. She kindly guided me through the POP era’s greatest hits: Andy Warhol’s Brillo boxes, Marylins, Elvises, Lichtenstein’s bombastic high impact comic book-style paintings to Oldenburg’s two mini-museums, one dedicated to American consumer items, another dedicated to mundane objects laid out at angles mimicking the shape of guns. If I thought I had sensed Neuburger’s unease upon admission of the institution’s cultural omissions, I felt it pronounced when she modestly pointed out the one artwork in the entire blockbuster show made by a woman - An installation titled La Visita (1964) by Marisol (b. 1930, Paris).

The basis of Ludwig Goes Pop was of course the vast Ludwig collection. Since the 50s, German power-couple Peter and Irene Ludwig voraciously collected American neo-dada and pop art by artists they presumed would be "art historically significant in the future" as per Neuburger. A self-fulfilling prophecy by way of their donations to several Institutions in Europe and abroad which in turn sealed the couple’s credibility with numerous accolades. As I went through several floors of what one could term hetero-normative art, I wondered how many POP-themed exhibitions have been repeatedly presented in museums all over the world and to what end. Neuburger, perhaps gauging my inclination, recommended I see Swedish film-maker John Skoog’s “VÄRN” showing in the Mumok basement. The film titled Redoubt (2014), which was the centerpiece of this exhibition, was a slow eerie narrative on Cold War paranoia that unraveled the true story of Karl-Göran Persson, a rural farmer in the flat-lands of South Sweden who turned his cottage into a fortress and refuge for himself and his community, prepared in the event of a probable Russian invasion.

Next door, Kunsthalle Wien showed Individual Stories: Collecting as Portrait and Methodology. Prominently serving as publicity for the show a sketch of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain. Or is it Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven's urinal that Duchamp later took credit for according to research by Irene Gammel and Amelia Jones? I felt dreadfully bored already. In the same vicinity the Leopold Museum brought together Egon Schiele, leading figure of early 20th Century Austrian art and contemporary British artist Tracey Emin. In Tracey Emin-Egon Schiele: Where I want to Go, Emin affiliated with her childhood hero Schiele by selecting some of his drawings that possibly connected to her practice. A visceral experience but still, not what I was looking for. Herwig Kempinger, President of the Secession who had attended my talk a few days earlier, offered a wonderful tour of the legendary space, Gustav Klimt’s Beethoven frieze from 1902, and their ongoing exhibition Cao Fei: Splendid River which had a light, experimental and humorous touch.

In Salzburg, the Museum der Moderne Salzburg showcased Experiments in Art and technology or E.A.T – an exhibition I could view only after paying for the elevator that transports one up to the museum and restaurant-with-a-view. With the exception of Japanese artist Fumiko Nakaya, E.A.T displayed works by Euramerican artists such as Jasper Johns, Jean Tinguely and Hans Haacke. And Andy Warhol. Obviously. With little patience for such cold ‘Conceptual Art’, and immense irritation from having paid for the elevator, I found some solace at the Museum’s older wing. Here was Charlotte Salomon: Life? Or Theatre? - An exceptional, captivating and beautifully presented exhibition of 278 gouaches painted by Salomon between 1940-1942 while in exile in France. Salomon's haunting visual diary that recollected key moments from her life that coincided with the turning point in Berlin’s history.

Her paintings, flitting ceaselessly between abstraction, figuration and textual elements, conveyed an emotive narration of cultural and political shifts during the 1930s that came at the cost of many lives including the artist's own. I found myself wracked with anxiety as I progressively viewed each painting without needing translations from German to English. This is what I was looking for- art with pathos, the kind that roused goose-bumps. To me, this compelling exhibition was not just about a young Jewish woman’s experience in Nazi territory but a tragic compendium of the human psyche. It was about the real consequences of political theatre that innocent individuals have to bear. It was as though in the blink of an eye, Salomon went from belonging to a respectable family to a refugee in exile away from her home and loved ones and at the mercy of strangers.

Charlotte Salomon’s Life? Or Theatre? left a deep impression on me as I pondered over how current refugees fleeing from actual war-zones, were being perceived by the rest of the world. And isn’t this the power inherent in art - its limitless capacity to evoke empathy for fellow human beings and prompt introspection on part of the viewer? Is art not an instrument through which to understand the other? Going further than Salzburg, I stopped at Kunsthaus Graz where the exhibition Landscape in Motion: Cinematic Visions of an Uncertain Tomorrow took its cue from pioneering works made - again - in Europe and America during the 60s. This exhibition did present an opportunity to watch Robert Smithson's film documentation on the making of Spiral Jetty among other interesting artworks but by then, having gone through a roster of contemporary institutions in Vienna, Salzburg and now Graz, I felt as though these establishments did not have the imagination or the daring to un-stick themselves from well-collected (and well-sold) white male art from the heyday of 60s and 70s. For whom were these 'blockbusters' that ultimately reinforce their own hegemony upon global art history and the international art market, culturally and commercially affirming their own worth by ignoring diverse practices from around the world. Having grown up and spent most of my life in West Africa and later Southeast Asia, I have developed an acute sensitivity to matters of race, representation and privilege. While in Vienna, Graz and especially Salzburg, I visited a number of antique stores where Asian and Oriental trinkets, talismans and decorative furniture were for on display for sale. While they were laced with exoticism they were not necessarily problematic but to my utter revulsion, I discovered racist figurines in high-end antique stores. The black body caricatured as passive-servile-docile-naif while 'tribal' was the sense I got from another store selling 'African' home decor. It would be a different matter were these items shown in a museum framed within objective critical discourse on historical issues of prejudice and bigotry. The obvious implication here is that there is an appetite for such 'collectibles' and that Europeans feel comfortable in their skin to sell and possibly profit from such items. This at a time when Black Americans are still fighting for legitimate recognition and respectful representation in social, political and cultural spheres. Similar is the dedicated struggle of African artists, curators, historians and critics in having their voices assertively heard in the international domain. And this, at a time while African and Middle Eastern refugees streaming into Austria are urging for compassion and humanitarian aid. Surely in Austria, one cannot imagine indulging in anti-Semitic speech much less feel bold enough to sell 'nostalgic' pieces that reinforce stereotypes of Jewish folk. So why such apparent lack of reflection when it concerns human beings with darker skin? And how far do such demeaning examples of nonchalant racism go in normalizing public attitudes and shaping official policies in today's day and age?

I reflected back on the 60s-centric exhibitions at the institutions I visited in the three cities. Still, keeping within the Euramerican context, what was that decade really about? - Cold War politics and protests. The African-American civil rights movement was in full swing; women contested gender disparity, equal wage; a war raged in Vietnam. Europe was forced to give up its colonies during this period though rarely facing up to the exploitation of African and Asian countries while the Cold War wrecked havoc on the Southeast Asia, the region still reeling from political decisions made in that era. Which public exhibition apart from John Skoog’s VÄRN at Mumok, discussed the realities of the human struggle beyond displaying an obsession with vapid consumerism, gun-culture and celebrity?

Towards the end of my stay in Vienna, I attended the 'Curated by_' panel discussions on contemporary art at the MAK, enthusiastically taking a front row seat so as to raise queries. During the break MAK Director Christoph Thun-Hohenstein complimented, even encouraged me on my line of questioning. However, in my experiences of art world conferences, I have observed more than a few to be lacking in substantive discourse, where respectable often established players offer fleeting, safe, non-committal responses to direct questions. Discussions at Curated_by also verified my initial observation that few diverse view-points exist outside a structure that is dominantly conservative, male and white - as is evident in the international market-sphere.

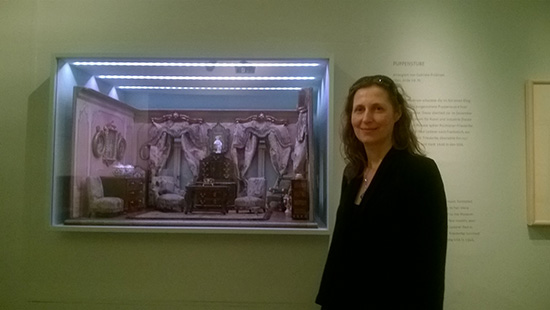

"I am the son of a refugee", said Johannes Wieninger, the Viennese curator at the Museum of Applied Arts and Design (MAK) as we discussed the immigration crisis over lunch one afternoon. In my search for global perspectives and cultural orientation, I changed strategy. I began to focus more on Vienna's exquisite historical museums while still engaging with diverse individuals from the contemporary art scene over enriching and enjoyable conversations. Making things fun was my host Kunsthaus Wien whose PR Head, Eva Engelberger, had me takeover their official Instagram account (@kunst_haus_wien) so I could post my encounters around Austria and interact with the museum's Followers. Kunsthaus Wien's new Director and change-maker Bettina Leidl was also on hand to guide me around Vienna's famous landmarks. As we walked from the Albertina through to National Bibliotheque, Leidl shared with me her years of experience working within the Austrian cultural sphere. As the Kunsthaus Wien preserves the legacy of Hundertwasser, it simultaneously frees itself from limitations that would otherwise keep the museum-site tied to its past. With an experienced team set in place by Leidl, two new spaces within the museum have been recently readied in order to engage with contemporary art, photography in particular. Evident from artworks I encountered especially in the basement gallery and the Garage, I gathered a genuine attempt to revitalize the museum as a forum for critical and open-minded discourse. Making it a relevant place for exchanges in the here and now, students of photography were encouraged to display their works within carefully curated exhibitions and discuss their work in public. One such artist was Belinda Kazeem who turned the practice of 'black-facing' on its head. Having found photo-negatives depicting a white person with black paint - and you can imagine the inversion showing white paint over a black face - Belinda challenged the dominant perception of 'white' as normal (with the rest of us silently relegated to Other). A writer and member of the Research Group on Black Austria Past and Present, Belinda was investigating decolonization and Black feminist empowerment. As with Salomon's artworks, I did not need a translator to understand the difficult questions boldly raised by Belinda for the public to consider. Kunsthaus Wien's other significant approach was to show experimental works by international contemporary artists who addressed global environmental and ecological concerns. Certainly here was an avenue to bridge artists from different regions that would connect through central themes. Leidl also directed me to the MAK which was the venue of Vienna Biennale. Upon getting there however, I found myself meandering through Mapping Bucharest: Art, Memory and Revolution 1916 - 2016. As art from different regions is about context and specific historical circumstances, I found it difficult to navigate this exhibition without any guidance or wall text. Allowing myself to wander aimlessly around the MAK, I found its collection of art and design from turn-of-the-century Vienna indicant of Japonism that influenced the Secession style; Mughal and European carpets from the 16th century; a Baroque Rococo gallery that held at its center a recreation of an 18th century porcelain room from the Dubsky Palace - oddly, curated by the founder of Minimalism, Donald Judd.

The MAK also exhibited an assortment of scrolls, ceramics, lacquer and other artifacts from Japan, China and Korea in an incredible display conceptualized by Japanese contemporary artist Tadashi Kawamata in collaboration with Curator Johannes Wieninger. One among many items of intrigue was a hardwood lacquer-imitation box from Japan's Edo period. This luxury object, dated 1640, has a form that follows pre-1600 Dutch models, combines the Japanese art of lacquering with Chinese style carvings and was made for European clients.

Over lunch with the senior curator at Cafe Pruckel, a typical Viennese coffee-house with legendarily rude waitstaff, I learned about Austria's ecumenical history through personal anecdotes. He recounted his father's experience; born in the early years of the twentieth century, 1905 in fact, his father was bewildered on the first day of school as he could not understand the many languages that other children communicated in. Wieninger informed me of the MAK's history, the Vienna World Exposition in 1873 (which was the first time the Meiji government of Japan participated in any international fair) and of overlapping influences from the East on Austrian aesthetic styles. Our conversation on Japan and China lead to the topic of Uli Sigg's collection of Chinese contemporary art. As per Wieninger, the Sigg M+ Collection, currently touring through a number of Western institutions before the fabled museum in the West Cultural Kowloon District of Hong Kong is ready (scheduled to open in 2019), will make its last stop at the MAK.

In the museum's possession among other fascinating treasures, was also the largest collection of the Hamzanama - a series of Mughal paintings depicting the adventures of the Prophet Muhammad's uncle Hamza, commissioned by Emperor Akbar in 1562. Wieninger informed me that some years back the MAK displayed their folios of miniature court paintings in Global Lab: Art as a Message - Asia and Europe 1500-1700. This exhibition purportedly explored numerous connections between the East and West. To aid my further education on this topic, Wieninger kindly provided me with a copy of the inch-thick exhibition catalogue. This publication held rich illustrations as well as essays from MAK curators and one by author Salman Rushdie. To my utter delight, Wieninger also showed me the museum-library and storage. Opening numerous cabinets, or wherever I pointed, he educated me on various sculptures, ceramics and even permitted me to handle a few delicate Asian porcelains. Similarly, Director of Dorotheum, Martin Bohm, also indulged me over an extended conversation while taking me through several floors and backrooms of the world's oldest auction house. Martin mentioned that the auction house once had in its possession the automobile in which Archduke Franz Ferdinand, nephew of Emperor Franz Josef and heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire, was assassinated in 1914 (the automobile is housed in the Museum of Military History, Vienna). I confessed that having tried and tried I still could not understand how exactly that incident sparked WW I. "Nobody does", he confidently assured me.

If it was historical connections to the present that I was searching for, then encounters with two Austrian contemporary artists were significant. Edgar Honetschlager, who was in attendance at my opening lecture on Southeast Asian art and Iranian-Austrian artist Ramesch Daha, both reviewed contested chapters in world history. While Edgar presented through his films historic cultural polarities and ideological contrasts between different regions - Japan and the West for instance, Ramesch had been investigating uneasy alliances between Iran and Austria since 1930s through her archival research, painting and installation-works. Both artists however, expounded concepts of political collusion, nationalist agendas, erased histories and revisionism, probing public memory whilst signaling how history might be in danger of repeating itself.

Similarly engaging was Christina Steinbrecher-Pfandt, Artistic Director of Vienna Contemporary art fair. Christina had also attended my talk and as we conversed she made personal connections with themes I had raised. As someone with German-Russian heritage living in Austria, she displayed an appreciation for hybrid culture and related to discursive motifs of marginalization and outsider perception, wherein one has no social or political sense of belonging within a dominant society. As she took me through parts of Vienna away from major tourist-sites, we settled on a small organic cafe where we sat and chatted about the Austrian art scene over some delicious cake. On another day, she even introduced me to some of Vienna's gallerists and showed me the site of Vienna Contemporary art fair.

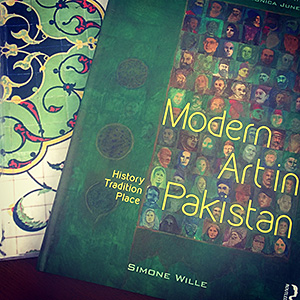

As Christina took the initiative to expand my horizons, so did Simone Wille, Austrian AICA member and scholar of Modern and Contemporary South Asian art. She generously provided me a copy of her recently published book Modern Art in Pakistan and we made numerous links between South and Southeast Asia. I was to discover later that her book had received a thoroughly glowing appraisal by Pakistani critic Nafisa Rizvi who assessed her hypothesis and thanked her for furthering pertinent scholarly discourse on art in Pakistan.  As I am not familiar with Modern Art from Lahore or Karachi, there was much to learn from her research. Eager to show me around and willing to ensure that I did not miss cultural peculiarities that Vienna's Museums had to offer, Simone wished to show me the 'Mughalries' of the Millionenzimmer at Schonbrunn Palace. On the appointed day, however, my timing being unforgivably tardy, we found ourselves brushing up against sweaty tourists disembarking from innumerable buses by 10 AM. I would have to make do by looking up Austrian academic Ebba Koch's publications on this subject online. We left the Palace and headed for the Museum of Military History instead, where to our relief, not a single visitor was in sight. Here, Simone brought my attention to Ottoman weaponry, insignia and two flags that were captured from the second Ottoman siege of Vienna (in 1683). Amongst the Tughs, batons, ornate muskets, tents, sabers, daggers, quivers, turbans, drums and whatnot, the enemy's flags were the most coveted by the Empire. Once captured, one of the Ottoman flags on display was originally sent to the Pope in Rome. The second, was paraded through the streets of Vienna as a relic of the vanquished enemy. Both flags, however, were displayed as propaganda for public viewing, a signal of the Christian Habsburg empire's superior might over foreign intruders. What I noted with fascination though, was how delicate and time-consuming craftsmanship had been employed to embellish objects of war and destruction.

As I am not familiar with Modern Art from Lahore or Karachi, there was much to learn from her research. Eager to show me around and willing to ensure that I did not miss cultural peculiarities that Vienna's Museums had to offer, Simone wished to show me the 'Mughalries' of the Millionenzimmer at Schonbrunn Palace. On the appointed day, however, my timing being unforgivably tardy, we found ourselves brushing up against sweaty tourists disembarking from innumerable buses by 10 AM. I would have to make do by looking up Austrian academic Ebba Koch's publications on this subject online. We left the Palace and headed for the Museum of Military History instead, where to our relief, not a single visitor was in sight. Here, Simone brought my attention to Ottoman weaponry, insignia and two flags that were captured from the second Ottoman siege of Vienna (in 1683). Amongst the Tughs, batons, ornate muskets, tents, sabers, daggers, quivers, turbans, drums and whatnot, the enemy's flags were the most coveted by the Empire. Once captured, one of the Ottoman flags on display was originally sent to the Pope in Rome. The second, was paraded through the streets of Vienna as a relic of the vanquished enemy. Both flags, however, were displayed as propaganda for public viewing, a signal of the Christian Habsburg empire's superior might over foreign intruders. What I noted with fascination though, was how delicate and time-consuming craftsmanship had been employed to embellish objects of war and destruction.  The muskets on display for instance, had handles that were decorated with floral motifs inlaid with mother-of-pearl and the Ottoman war-tent was liberally ornamented with dense applique and embroidery, among other magnificently adorned items.

The muskets on display for instance, had handles that were decorated with floral motifs inlaid with mother-of-pearl and the Ottoman war-tent was liberally ornamented with dense applique and embroidery, among other magnificently adorned items.

Permitting myself a recess from art, I made time for an Opera performance at Schonbrunn Palace, a piano concert in the basement of an old chapel, the Naturhistorisches Museum where the Venus of Willendorf was on display in a dismal corner, the Habsburg Palace and the Kunsthistorische Museum. At the Palace were a number of ceramics that were either influenced by Japan and China but made by Viennese manufacturers or imported from the East and then gilded with gold and silver locally. At the Kunsthistorische, among ancient Egyptian and Greek relics, was the Kunstkammer that opened in 2013 after a decade of renovations. Kunstkammer loosely translating to Cabinet of curiosities held a wondrous collection of exotica amassed by the Habsburgs over roughly 650 years. Spread out across twenty rooms were jaw-dropping objects particularly of ivory, gold, coral, and precious stones, some of which were made in Sri Lanka, Goa, Gujarat or the Deccan between the 16th and 18th centuries. The earliest documented and preserved object from these was Elephant with Salt Cellar dated 1550. The rock-crystal carving of a small elephant was made in the Deccan region, acquired by Catherine of Austria and Queen of Portugal who then had it combined with an older salt cellar from Lisbon. Here was a hybrid object that came together with parts of different origin to contemporary and unique fashion. I couldn't find a more endearing metaphor for cultural cosmopolitanism even if I tried.

I visited the glorious Austrian National Library as well but when I caught up with Simone Wille once more, she pointed out that I had missed the Globe Museum in the same vicinity. So, off we went to the Globe Museum together on my last day in Vienna. Apparently the only public collection of Globes in the world, the museum displayed among many items, a terrestrial globe made by 16th century Dutch cartographer Gemma Frisius, mathematical instruments, centuries old books on astronomy and examples of tellurions and orreries (rudimentary model-contraptions that approximate the distance of the sun from the planets). The visit to Globe Museum was followed up with a quick tour of the Jewish Museum Vienna (JMV). Curator and AICA board member Andrea Winkelbauer very kindly took some time off her busy schedule to guide me through the museum. I recalled that when we first met she mentioned her research into Jewish women artists between the two World Wars which would lead to an exhibition in 2016. Charlotte Salomon for instance would feature as would Austrian artist Marie-Louise von Motesiczky (1906-1996) whose family history and paintings were part of the permanent exhibition.

Among JMV's collection, most fascinating for me were objects that seminal Jewish patrons collected. A glimmer of this 'global' outlook that I had found in aforementioned museums, where an influx of foreign ideas contributed to the cultural wealth of an empire, is what I found in these collections from before Austria closed itself off in the late 30s. The Chushingura Drama (perspective drawing), a coloured woodcut from Japan dated 1800 features alongside a Maori ancestor figure and a club of a Maori chief from New Zealand also dated around 1880. The Maori objects were borrowed from the collection of Weltmuseum Wien (Museum of Ethnology) and as I read the label I realized I would not been able to see the Weltmuseum's Asian collections as they are closed for renovations, only to open sometime in 2017.

Housed on the top-most floor of the JMV is the storage that doubles as an excellent exhibition site. The Visible Storage: Collecting and Remembering is a remarkable approach to storage and display of numerous carefully positioned items that not only provide an insight into the museum's collection but literally make visible the roster of gifts and acquisitions in a transparent and systematic manner. An approach that could be adopted by small-scale museums in Asia. Objects that might never make it into themed exhibition programming would still be on display here. For instance, I wouldn't imagine the nineteenth century anti-Semite walking sticks that caricature the "Jewish Nose", could ever be on display in any exhibition. But here they were, walking sticks carried by Karl Ritter von Schönerer (one of the masterminds of Anti-Semitism) and his followers, seen within clear context and labeling - unlike the racist black figurines I found on sale at antique stores across Austria.

As Andrea guided me through the JMV's permanent galleries, she brought my attention to Berta Zuckerkandl-Szeps (1864-1945), a seminal art critic and journalist who promoted modern artists such as Klimt and the work of architects such as Otto Wagner and Josef Hoffman. My further reading on Berta revealed her to be a courageous pacifist and humanitarian active during WW I, calling for peace at the same time urging the Viennese for tolerance towards refugees streaming into Austria from the Eastern provinces. Berta was a pioneer, progressive and liberal who used her voice to speak for the disenfranchised. She advocated for the place and role of art in society especially in Inter-War Vienna, when doing so would have undoubtedly involved a personal cost. As I left the JMV, I made a mental note to find translations of this early feminist's texts.

My last stop was the Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial designed by British artist Rachel Whiteread, a short walk away from JMV. The austere gray concrete inversion of a library made for a tranquil spot for introspection. Rows of cement-books stacked on all four sides stood unyielding, not unlike a sealed fortress of knowledge and cultural wisdom that can never be accessed. I wondered about my maternal forefathers who were forced into leaving their ancestral lands well before the Partition divided India. The Statelessness, unbelonging and Outsider identity has since embedded itself in our diasporic outlook as access to heritage - cultural, lingual and otherwise have been vastly limited. In this, the Sindhi folk who originate from Sindh, Pakistan, certainly share in with the Jews and all of those who continue to be displaced and dispossessed.

I was psychologically (and emotionally) ready to see the Sigmund Freud museum, but my time was up. Four weeks had passed and my Residency had reached its end. But I had barely begun to scratch the surface of Vienna. However, through a personal journey of questioning and discovery, I had been nurtured indeed in strength and intellect. Going beyond any superfluous expectation or reservations I may have had before embarking on this Residency, I was warmly surprised by the knowledge and access granted to me by immensely generous individuals who made the time. What I gained, among new friends, was precious guidance and encouragement to continue as an empowered Critic with renewed vigor.

Bharti Lalwani is an art critic who contributes to The Art Newspaper, Harper's Bazaar Art Arabia, Eyeline (Australia), and Asia-Europe Foundation's portal Culture360.org, among numerous international art journals. Her research interests include Private museums as well as contemporary art from Southeast Asia, the Middle-East and West Africa. Through her writing and research she connects the emerging contemporary art histories of three continents.

In 2014, Lalwani was nominated Forbes Art Writer of the Year (India), and she has also been nominated from Singapore, Thailand and The Philippines for Best Writing on Asian Contemporary Art for The Prudential Eye Award. In 2015, she was founding-resident at the AICA-Kunsthaus Wien Art Critic Residency. Bharti Lalwani holds an MA in Contemporary Art from Sotheby's Institute (Singapore) and a BA in Fine Art from Central Saint Martins (London).