December 29, 2015

Art and Social Engagement in Yogyakarta, Indonesia: Ketjilbergerak and the Legacy of Taring Padi

Written by Katherine Bruhn

Taring Padi and Reflections in the Mud

On May 29, 2006, near Sidoarjo, East Java, the world’s largest mud volcano began to erupt. This eruption, the result of the blowout of a natural gas well owned by PT Lapindo Brantas, led to a mudflow that at its peak spewed mud at rates as high as 160,000 cubic meters per day. The devastation caused by this disaster damaged thousands of houses, agricultural areas, plantations, and over twenty factories. With no place to work or live, tens of thousands of people were forced to leave behind their homes. While thousands have been affected by this disaster, little compensation has been given to victims due to Lapindo’s unwillingness to admit fault and the government’s failure to intervene.[1]

In May 2010, in order to help the people of Sidoarjo commemorate the fourth anniversary of this disaster, Taring Padi, a political art collective from Yogyakarta, Central Java joined the people of Sidoarjo for a four-day collaborative project. Known as “Reflection in the Mud,” this project focused on reviving the collective memory of the Sidoarjo community. Taring Padi invited participants to communicate their feelings about the loss and sorrow caused by the Lapindo disaster while encouraging individuals not to dwell on their pain but rather to continue the fight for their rights. With the growth of a collective memory, Taring Padi hoped that cultural ties would be reinforced, breaking down tension that had grown amongst victims. The development of a collective memory was intended to not only reinforce solidarity between victims but also to serve as a statement to the public that similar incidents cannot happen again. While in Sidoarjo the artists of Taring Padi organized workshops to teach community members the techniques of woodblock and screen-printing. People of all ages joined in these workshops, creating posters, banners, and T-shirts with messages that read, “Gasmu meracuni tubuh kami” (Your gas is poisoning our bodies), “Kembalikan tempat bermain kami” (Give us back our place to play), and “Kami menolak jadi korban” (We refuse to be victims). The posters and banners, along with wayang (Indonesian shadow puppets) and masks created by workshop participants were used in a parade held on the last day of the collaborative event [figure 1].

Carrying the puppets, banners, and masks over the mud, these objects were intended to symbolize the oppressors who had robbed residents of their livelihoods, voices, and histories. This parade ended with a carnival and concert where citizens and artists alike sang together, expressing their discontent and continued concerns for the future of those affected by disaster and corruption.

Taring Padi’s work with the community of Sidoarjo is exemplary of this group’s engagement with local communities in Indonesia and abroad. Artist Dolorosa Sinaga describes the emergence of Taring Padi in December 1998, shortly after the fall of Suharto’s oppressive 32-year New Order regime stating, “Through art, they began building an understanding amongst the people to fight against injustice, helping to forge a community aware of environmental, social, political and cultural issues, inviting the community to be active and courageous in voicing their real life experiences and their opinions on the performance of government.”[2] With a desire to continue the fight of the student movement, which had played a key part in the demise of the New Order, the founders of Taring Padi set forth with a goal: to create art that would both help to educate and give voice to marginalized communities. Work created by Taring Padi never holds the signature of a single artist but rather is the product of the collective and the communities they work with. While the production of art is a significant aspect of their work, the process of communication and collaboration is held superior to the production of objects. This type of art practice can, in part, be seen as a type of “social practice” or “socially engaged” art.

Definitions of Social Engagement and the Politicization of Contemporary Indonesian Art(ists)

Since the 1990s the idea of social practice or socially engaged art has gained global attention. Yet, despite its emergence in locales as diverse as Europe’s urban centers, rural villages in Indonesia, and presentation at international biennales, it is also arguable that this type of art remains difficult to define or identify due to the lack of a clearly articulated language used to describe it. In the last two decades various names including “relational,” “dialogic,” “littoral,” and “living-form” have all been associated with such projects. While each definition differs slightly, at the core of these associated forms is a desire of artists to engage audiences in the process of production. Art historian Claire Bishop describes this type of art as a response to contemporary capitalism stating that in order to “re-humanize a society rendered numb and fragmented by the repressive instrumentality of capitalist production” socially engaged artists value what is made invisible in the process of an art object’s production, namely a group dynamic, a social situation, a change of energy, a raised consciousness.[3] In another vein, art historian Grant Kester, responsible for coining the term “dialogic” in relation to such art, argues that work included within varied definitions of such social practice should not be viewed as a movement but rather as an inclination in the work of artists over the past thirty years. Describing the development of this trend, Kester references community art traditions in the United Kingdom and temporary public art in the United States. He points to art practices of the 1960s and 1970s that led to happenings and performance-based actions. Further, he stresses the impact of alternative spaces and community-based art projects in the 1980s, as influential in the development of a disparate network of artists and collectives that have come to be associated with socially engaged art. While disparate, Kester argues that these groups are united by “a series of provocative assumptions about the relationship between art and the broader social and political world and about the kinds of knowledge that aesthetic experience is capable of producing.”[4]

Turning to Indonesia, the argument that Indonesian modern artists are “socially engaged” is not new. While groups like Taring Padi reflect a contemporary engagement of artists with the rakyat or Indonesian people, similar interests date back to Indonesia’s first modern artists. Beginning in the 1930s with the work of individuals including S. Sudjojono, Affandi, and Hendra Gunawan, an art ideology developed that stressed awareness of the rakyat. Art historian Caroline Turner describes how these artists, considered the fathers of Indonesian modern art, “emphasized an art that embraced a vision of freedom encompassing all levels of society.”[5] Organized collectively around sanggar or artist workshops, these artists championed a style described as “socially engaged realism.”[6]

Jumping forward to descriptions of generations that followed, namely artists of the New Order period, art historian Astri Wright states:

Many of the painters in their late thirties and early forties (artists born in the 1950s and 60s) refer to themselves as “socially engaged,” an engagement, which embraces social, political, and aesthetic dimensions. These artists are protesting against the older generation’s definitions of art, aesthetics, and “Indonesian-ness.” In their art they attempt to express reality as they see it rather than according to the idealist and romantic modes of representation they see prevailing in the established Indonesian art world…Their work reflects contemporary life in Indonesia, with its commercialism, its urban-rural polarities, and what they experience as increasing social alienation.[7]

Wright considers the artists described throughout her monograph, Soul, Spirit, and Mountain: Preoccupations of Contemporary Indonesian Painters, as “variations on the theme of what has been called the politically or socially engaged artist”. Meanwhile, the definition of “socially engaged” used by Wright and other Indonesian art historians is quite different than that which I apply to the work of artists like Taring Padi. Although artists of the revolutionary generation (1930s – 1945) and New Order period (1965 – 1998) created art that attempted to represent or critique the sociopolitical situation, these artists did not engage directly with the subjects they depicted. I suggest that the notion of “social engagement” in the work of many Reformasi and post-Reformasi (1998 – present) artists or art communities moves away from mere representation to literal engagement that serves as a key component in processes of production. The work of many contemporary Indonesian socially engaged artists is intended to “enter into life” in order to have a direct impact on society, becoming what curator Nato Thompson and New York based organization Creative Time describe as “living form.”[8]

The idea of “living form” emerged in conjunction with a 2012 project that sought to highlight socially engaged practices from countries throughout the world. As part of this project, Creative Time published, Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art From 1991-2011, in which the organization’s curator, Nato Thompson, explains that socially engaged art practice should be seen as a “living form” located in the “real world” (i.e. public spaces and public forums). Like Grant Kester, Thompson argues that this art is not simply a movement nor can it be reduced to a particular name. Rather, Thompson suggests, if seen as a “new social order,” the cultural practices associated with such projects that span disciplines ranging from urban planning and community work to theater and the visual arts, indicate ways of life that emphasize participation and challenge power.[9] Produced in a way that takes focus away from the aesthetics of an object, the “form” or lack thereof of this art allows viewers to focus on how a work approaches the social, as opposed to simply what it looks like.[10]

While groups that create such art have varying objectives and outputs, Claire Bishop suggests that all are linked by a belief in the empowering creativity of collective action and shared ideas.[11]

When Taring Padi emerged in December 1998, it was in a context characterized by greater freedom of expression, the rapid development of local civil initiatives, and the increased politicization of all spheres of life, including art. Throughout the 1990s, Indonesian art represented at international exhibitions had focused largely on themes including violence, communal trauma, identity, and gender equality. The continued depiction of these issues, however, eventually became a point of contention within the local art world. Although artists such as Nindityo Adipurnomo and Mella Jaarsma (founders of Indonesia’s first alternative gallery, Cemeti Art House), Heri Dono, Tisna Sanjaya, and Arahmaiani (to name a few) had become recognized internationally for their production of politically oriented art, after 1998 the work of many artists that attempted to follow such trends, was described as one-dimensional and non-reflective.[12] In her curatorial text from the 2000 exhibition, “AWAS! Recent Art from Indonesia,” German art historian Alexandra Kuss states:

Under conditions where it is no longer dangerous to criticize the regime, among established artists and art college students alike, many have become ‘reporters’ of socio-political chaos. The flood of such political works…could be summarized in just one sentence as ‘one-liners.’ In this sense some recent developments in Indonesian art seem to be heading towards a one-dimensional engagement with political responsibility as if it was a ‘compulsory exercise’ in art.[13]

In this context groups like Taring Padi were significant for their focus on strategies that would allow their art to interact more fully with the issues depicted and the people represented. Ignoring the demands of commercial markets or international fame, the members of Taring Padi focused instead on how their work could help give voice to the concerns of oppressed communities, particularly those composed of farmers and laborers.

Living in Yogyakarta over various periods from 2010 to 2015, I have become familiar with many artist groups and creative collectives that call this city home. Known as one of Indonesia’s art hubs, Yogyakarta is unique for its density of art spaces and artists. Home to Indonesia’s oldest art institute, the Indonesian Institute of Fine Arts, established in 1949 shortly after independence, Yogyakarta now boasts over fifty art and cultural spaces. In this city, one can find groups associated with “fine arts” – painting, sculpture, etc. – as well as puppet and theatre troops, photography and film collectives, and cultural studies centers. Today artists and young people have the ability to find their “niche” in one of Yogyakarta’s many creative communities. Yet, at the same time, with the development of a more diverse arts infrastructure as well as a stronger commercial market, young artists must also consider with greater care how they wish to position themselves as either alternative to or in-line with the more mainstream commercial market. Although the possibility of commercial success is a greater reality for artists today than it was two decades ago, the freedom to challenge authority in public spaces has also increased. In order to provide insight into the growth of communities that can be associated with ideas of social engagement I highlight the work of one creative community known as Ketjilbergerak (loosely translated as “small movements”). The work of this group both with communities outside of the art world and increasingly at Yogyakarta’s large scale art events, provides perspective regarding the continuation of socially engaged or participatory art practices in the last decade, following the work of groups like Taring Padi during the Reformasi period.

Ketjilbergerak

In 2006, students from Sanata Dharma University, a Jesuit institution located in Yogyakarta, formed Ketjilbergerak as a discussion based group. Frustrated by what they perceived as a lack of critical discourse amongst university students, Ketjilbergerak’s initial goal was to create a forum in which to raise awareness of socio-political issues. By doing this, they hoped to continue the legacy of the student movement and activists who in the 1990s fought for political change. Today, a decade after its formation, Ketjilbergerak has developed into a dynamic group – part community engaged artists, part social activists, and part community educators. Ketjilbergerak’s projects are varied in form and intent. While at times this group’s work involves the use of gallery space for the display of typical art exhibitions, Ketjilbergerak’s projects also, almost always, involve correlating activities situated in public or alternative spaces intended to involve a wider, more general audience. It is a primary goal of Ketjilbergerak to facilitate activities that will serve as alternative forms of education with art as the mediating language. Two projects that demonstrate the goals of this group and its dialogic nature include a workshop held in August 2014 and the group’s more recent participation in Yogyakarta’s annual art fair, ArtJog.

A Community Workshop at Suroyolo Peak

Located on the border of the Special Region of Yogyakarta and Central Java, Suroloyo Peak is approximately 40 kilometers from the city of Yogyakarta. On a clear day, the 9th century temple, Borobudur and Java’s four largest mountains Merapi, Merbabu, Sumbing, and Sindoro are visible. It is believed that Suroloyo Peak is a mythical site both in relation to the history of the Mataram kingdom and the myth of the Punakawan or the “clowns” of Javanese Wayang or shadow puppetry [figure 2].

The workshop held near Suroloyo Peak was planned in collaboration with a group of undergraduate students from Yogyakarta’s Gadjah Mada University as part of a larger event titled “Gotong Royong di Suroloyo.” The term “gotong royong” refers to a concept central to Indonesian society that stresses the importance of cooperation and reciprocity. Here, the idea of gotong royong was used to highlight the necessity of supporting and sharing local culture. As part of “Gotong Royong di Suroloyo,” Ketjilbergerak’s workshop involved the collaborative production of “wayang suket” or grass puppets [figure 3] and more significantly, a discussion of local history intended to get at issues faced by young people in areas such as Suroloyo that remain relatively isolated due to access.

Doni, one of the Gadjah Mada students responsible for the coordination of the larger event and a member of Ketjilbergerak explained that Suroloyo Peak has become an attractive tourist destination largely because of the site’s beautiful vistas. However, many visitors, especially those that are younger, are not aware of Suroloyo Peak’s historical significance. In order to learn more about this area and find ways to promote its history as a part of the region’s touristic draw, Doni and his Gadjah Mada classmates chose Suroloyo Peak as the site for a volunteer project, part of a requirement for all university students in Indonesia. In planning the Gotong Royong Festival, Doni invited Ketjilbergerak to join, as he is also one of the group’s “fluid” members.

In the last two years Ketjilbergerak has become increasingly active due in large part to a rapidly growing network built via social media. Ketjilbergerak’s strategic use of social media has led to the involvement of young people both close to home in Yogyakarta and further afield in cities throughout Indonesia. With an increasingly large virtual following the membership of Ketjilbergerak is not solidified, but fluid, allowing any and all to participate in the varied activities that have become a part of Ketjilbergerak’s platform. Individuals like Doni who consider themselves Ketjilbergerak members do not necessarily join each event coordinated by the group. However, they do carry the attitude of the group with them in other activities. As Vani, one of the group’s founders described, those that are regular participants in Ketjilbergerak’s activities have increasingly branched out initiating their own projects, acting as leaders amongst their peers.

While I have met a number of Ketjilbergerak members time and again, each time I join an activity, without a doubt, I have the opportunity to meet someone new that has been inspired by Ketjilbergerak’s mission. Vani explained that each week she receives numerous messages via Twitter or Facebook. These messages are from young people both in and around Yogyakarta as well as cities throughout Indonesia asking how they can be a part of Ketjilbergerak. Vani stated that many of these individuals are looking for a way to create stronger ties be it close to home or further afield. These young people are looking for inspiration and new, creative ways to improve their communities.

The evening we arrived to Suroloyo Peak we met with members of Keceme village’s Karang Taruna youth organization. Karang Taruna is an organization found in villages throughout Indonesia whose focus is to engage in economic development utilizing locally available materials or products and social empowerment activities. It is common for Ketjilbergerak to work with members of a village or region’s Karang Taruna. By doing this they are able to understand in more depth the needs of that particular area while also learning about local history and products or crafts that are unique to that region. Prior to our arrival, members of Ketjilbergerak had already had preliminary meetings with members of Keceme’s Karang Taruna. After learning the significance of wayang mythology to Suroloyo Peak, wayang suket seemed an obvious medium in order to illuminate this history. In addition, materials needed to make these puppets – grass fonds – are easy to find in this area.

In each of their workshops or events Ketjilbergerak tries to teach participants a new, practical skill that they will be able to utilize after the workshop. If not teaching a new skill, Greg, another of Ketjilbergerak’s founders describes the importance of promoting new ideas in order to empower participants. Two of Ketjilbergerak’s more regular events are reflective of this goal. These events known as “Kelas Melamun” and “Ben Prigel” invite local artists or cultural practitioners from Yogyakarta to share a skill with those in attendance. While Kelas Melamun focuses more on discussion, Ben Prigel, a Javanese term that means “supaya trampil” or “to be skilled” takes practice and skill building as its goal. With any activity initiated by Ketjilbergerak a primary goal is to train young people to become independent thinkers with strong leadership skills.

Ketjilbergerak began their work in Keceme village with an explanation of how to create wayang suket. Without much hesitation members of Ketjilbergerak moved amongst the youth of Keceme to help teach this new craft [figure 4]. As we sat together laughing at each other’s struggle, the conversation quickly shifted to a discussion of the local place and the relevance of Suroloyo to wayang mythology. Through this conversation we learned not only more about the history of Suroloyo but also the lived realities of this region.

Although residents of Keceme live only 40 kilometers from Yogyakarta, their community’s location, atop one of the region’s highest mountain peaks, makes it a challenge to reach services such as secondary schools and hospitals. While many of Keceme’s residents are coffee farmers they do not sell their product on a large scale. Instead they rely on tourists who come to Suroloyo in order to visit its mythical sites or trek to Borobudur. Wayu, a member of Keceme’s Karang Taruna, described how in the past, residents of this region had attempted to hold an annual festival in honor of the region’s history. However, with lack of outside support or resources they had struggled to plan the event on a consistent basis. Hearing from Ketjilbergerak about the creative activities of young people in other regions of Yogyakarta facing similar challenges, the members of Keceme’s Karang Taruna were intrigued. They were excited about the possibility of connecting with a network of young people that would aid in their planning and execution of future cultural events. This possibility became the focus of our conversation and the more significant product of the workshop.

After an evening spent creating wayang suket and sharing stories with the residents of Keceme, the members of Ketjilbergerak headed back to Yogyakarta. Before leaving, however, plans were made to continue the newly formed partnership, the first step being to connect Keceme’s Karang Taruna with other communities throughout Yogyakarta. By continually building a network of youth communities in and around Yogyakarta and throughout Indonesia, Ketjilbergerak has become a catalyst. This workshop is only one example of how Ketjilbergerak, through small-scale events, focused around dialogue and communication is working to promote local collaboration by building a network of young leaders and community activists. The art object produced during the workshop is secondary to the relationships formed. While this event is reflective of Ketjilbergerak’s work with communities that hold no connection to Yogyakarta’s art world, my most recent opportunity to assist Ketjilbergerak with their community engagement took place at the annual art fair, ArtJog, allowing further insight regarding Ketjilbergerak’s position in the “commercial” art world.

Audience Engagement at Yogyakarta’s Art Fair, ArtJog

Now in its 8th iteration, ArtJog is held each year in the weeks leading up to the Islamic holy month of Ramadan at Yogyakarta’s Taman Budaya or Cultural Center. This art fair is unique because of its bottom-up approach. Organized by and for artists, ArtJog has eliminated galleries as a necessary middleman in the sale of artwork as is generally the case at art fairs. Each year the number of attendees increases. ArtJog has become a highly anticipated event by an increasingly large public that hails not only from Yogyakarta and its surroundings but also cities and countries further afield such as Jakarta, Bandung, Surabaya, Singapore and Malaysia. One particularly unique feature of this event in comparison to other Yogyakarta art events is the annual construction of a commissioned installation that takes over the façade of Taman Budaya. This year’s commissioned artist was the group Indieguerillas assisted by Ketjilbergerak.

Indieguerillas, formed in 1999, is a husband and wife duo from Yogyakarta. Their work is known for its unique inter-media experimentation and reference to both traditional and contemporary culture. ArtJog director Heri Pemad stated that Indieguerillas was chosen to create the commissioned work for ArtJog because their work was considered most suited to the exhibition’s theme “Infinity influx: The Unending Loop that Bonds the Artist and the Audience.” A primary goal of this year’s ArtJog was to create an interactive or participatory experience for attendees; a goal reflective of a growing interest throughout Indonesia’s art world in work that engages more directly with its audience.

Playing off the literal translation of Taman Budaya or “Cultural Park” Indieguerillas created eight interactive pieces fashioned as bicycles. Each bike was given a particular theme that made reference to either traditional culture or a perceived problem present in contemporary society. Displayed inside of a large dome covered by live plants [figure 5], the entire installation was intended to create the effect of a garden or (cultural) park. While visitors were invited to interact freely with each piece, the efforts of Ketjilbergerak enhanced this experience, in particular for those who visited ArtJog each evening.

Amongst Indieguerillas’ work were bicycles fashioned as a moving market for the sale of locally designed products, a rocking barbershop, a portable kitchen, and a table for two where those seated were separated by a partition [figure 6]. This partition featured small video screens that allowed each person to see the other but prohibited communication, intended as commentary on society’s fascination with cell phones during all moments of the day even dinner. During the day these pieces lay silent, dependent on the interaction of the viewer. While each evening, through coordination by Ketjilbergerak, various community groups, individuals, and local artists helped operate each bicycle or booth, quite literally bringing the installation to life.

Speaking with Santi Ariestyowati of Indieguerillas she explained that Ketjilbergerak was the perfect group to help coordinate the actual functioning of the various bicycles, which was a key component in the overall execution of the installation. Ketjilbergerak was perfect Santi explained, because of their extensive network and ability to effectively execute collaborative projects as well as their interest in and commitment to direct engagement with their audience. On the evening that I visited ArtJog I had the opportunity to purchase the product of local designers who call their brand “Javanese Contemporary Goods,” eat a tuna sandwich cooked by members of Ketjilbergerak at the portable kitchen [figure 7], and experience the partitioned table aptly titled “Face Off Dinner.” In addition, I observed Ketjilbergerak taking advantage of the large crowd, to execute another of their recent projects entitled “Benih Bunyi #3” or “Seeds of Sound #3.”

Seeds of Sound

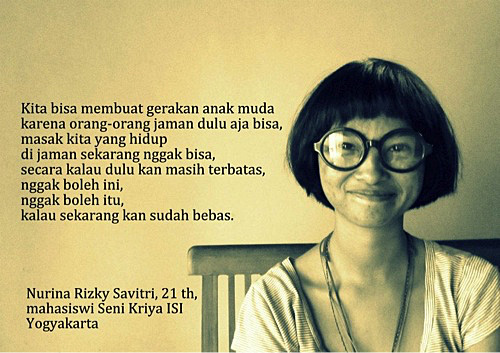

In 2012, Ketjilbergerak began their first iteration of Benih Bunyi. Through interviews this project was intended to elicit the opinion of young people regarding their place in Indonesian society. Over the course of forty days, members of Ketjilbergerak interviewed over 180 people. A photo was taken of each interviewee. These photos along with a key quote from the interview were then shared via Facebook. While simple, these images provide concise statements, conveying a sense of disappointment amongst youth regarding the present state of Indonesia. The image in figure 8 depicting a 21-year old female student from Yogyakarta’s art institute is just one example. It states, “We can make a youth movement if our ancestors could, how is it possible that our generation can’t do this, before there were still limitations, you were not allowed to do this or that, but now, we are free.” The final analysis of all 180 interviews resulted in a statement containing five points regarding the overall view Indonesian youth hold of their nation and their role in its development:

Indonesian youth are disappointed with and pessimistic towards Indonesia. Indonesian youth today do not believe in one another. Indonesian youth need a means through why they can become one. Indonesian youth need to form a movement together in order to change the situation. Indonesian youth want to be able to empower themselves and create synergy with the people in order to advance together.[14]

Due to the positive reception of this project, it was repeated again in 2014 focused on the theme “berbeda itu biasa” or “different is normal” and in 2015 with the theme “mulai dari yang dekat.” Loosely translated as “begin with what we know,” the third iteration of Benih Bunyi focused on the issue of land and what has in the last two years been the rapid development of commercial properties, especially hotels, throughout Yogyakarta.

While helping to coordinate the actual functioning of Indieguerillas’ installation, the members of Ketjilbergerak took time to interview ArtJog attendees asking them to explain the significance of land. In general, these interviews were conducted in front of Indieguerillas’ work where a photo was snapped of each interviewee. Again, these photos were uploaded to social media via both Instagram and Facebook, presenting critical statements regarding the significance of land as an important natural resource and as the site one calls home. An example can be seen in figure 9. This image depicts Boy, a resident of Yogyakarta standing in front of the Indieguerillas’ “rocking barber shop.” Boy’s statement reads, “Land is the most basic element. Almost everything on Earth comes from the land.” While the interaction between Ketjilbergerak and Boy took only minutes, the virtual archive that this photo became a part of allows for an extended interaction amongst a wider audience, namely Ketjilbergerak’s followers on social media. Scrolling through the Facebook album that contains these photos Boy’s straightforward statement is enhanced by the shared opinion of his peers, while being made part of a collective experience [figur 10]. As Grant Kester states of dialogic art more important than an instantaneous, flash of insight is the relationship created between the viewer and the work of art, from its inception, throughout the process of production, and in its reception.[15]

A Legacy of “Do-It-Yourself” Production and the Place of Socially Engaged Art Practice

As the various projects described throughout this article demonstrate, the work of Ketjilbergerak cannot be situated within a more familiar category of fine art such as painting or sculpture, nor does it generally result in the production of a standard art object. While on one hand, workshops such as that held at Suroloyo Peak resemble the work of NGOs interested in community empowerment and rural development, on another hand, Ketjilbergerak’s role at ArtJog appears similar to that of an event organizer. Why then is this group recognized as part of Yogyakarta’s art world as indicated by their presence at events like ArtJog and Yogyakarta’s most recent biennale, held at the end of 2015?

As the theme of this year’s ArtJog, “Infinity Influx: The Unending Loop that Bonds the Artist and the Audience” demonstrates, there is an expressed desire to situate the work of Indonesian contemporary artists within the historical trajectory of participatory or alternative art forms, characteristic of historical movements, in this case Fluxus. Regarding the connection to Fluxus, the curatorial statement of ArtJog states “More than simply celebrating Fluxus, “Infinity in Flux” realizes the importance of artwork that is “limitless” in a world that is increasingly so; artwork that is not limited by a singularity of media – artwork that engages and provokes all of the senses.” The work of Ketjilbergerak and its reception is indicative of an important shift in the perceived utility of creative work that yields discourse and collaboration rather than a tangible “art object” even in commercial spaces like Yogyakarta’s annual art fair, ArtJog. It represents the continuation of a “do-it-yourself” ethic that existed amongst activists and organizers leading up to and during the period of Reformasi beginning in 1998 with the end of Suharto’s New Order. British artist, Andy Abbot, in an article on the ethics of do-it-yourself (DIY) in self-organized art and cultural activity, describes how such action is born out of a void or a perceived lack. Abbot argues that working collectively in alternative spaces breeds a more organic understanding and attachment to a politics that challenges both capitalist and state orthodoxy. With DIY activity, there is a sense of pride and ownership over outcomes; there is the transparency of process and control afforded by doing something DIY; and there is the necessarily collective aspect, where pooling resources, skill-sharing and generally having a go at the things normally reserved for “professionals” leads to new abilities and novel approaches; outcomes that are also characteristic of art deemed socially engaged.

During the 1990s, a do-it-yourself culture emerged in Indonesia amongst activists, sub-cultures (i.e. punk communities), and artists. Leading up to Reformasi such communities began to challenge the repression of Suharto’s New Order through DIY organization. Comic books and fanzine were used as alternative media to connect communities and share ideas. Prior to Reformasi, artists that challenged the regime usually did so in international forums as the fear of Suharto’s authoritarian regime remained a real and constant threat. It was not until after the start of Reformasi that groups, such as Taring Padi, were able to aggressively confront issues that were the result of three decades of New Order rule, engaging directly with communities outside of the art world.

Today, almost two decades after the fall of the New Order, communities and collective initiatives that embody the DIY spirit flourish in urban centers like Yogyakarta and increasingly throughout more rural regions of Java and Indonesia’s outer islands. While such organization allowed groups in the 1990s the ability to challenge the regime, today it allows groups like Ketjilbergerak to confront contemporary concerns related to corruption, education, and capitalism. Whereas Abbot, in his discussion of DIY activity states, “Few people who desire to change the world would think the best way of going about it would be to start a band, run a record label, form an art collective, perform street interventions or create counter-institutions,” many Indonesian artists who embody the DIY spirit through the production of what might be characterized as socially engaged or social practice art do in fact intend to impact society and effect change through their practice and engagement with local communities.

Katherine Bruhn is a third year PhD student in the Department of South and Southeast Asian Studies at the University of California Berkeley. Her dissertation project focuses on the history of Indonesian modern art since the 1950s and its intersection with a more recent government interest in the development of Indonesia’s creative economy. Bruhn's interest in the history of West Sumatran modern art stems from an interest in proposing a peripheral or revisionist history of Indonesian modern art.

[1] Heath McMichael, “The Lapindo Mudflow Disaster: Environmental, Infrastructure and Economic Impact,” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 45 (2009): 73-83.

[2] Dolorosa Sinaga, “Not for the Sake of a Fine Arts Discourse,” in Seni Membongkar Tirani, ed. Annie Sloman et al. (Yogyakarta: Lumbung Press, 2011), 28.

[3] Claire Bishop, “Participation and Spectacle: Where Are We Now?” in Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art From 1991-2001, ed. Nato Thompson (New York: Creative Time Books, 2012), 35.

[4] Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 9.

[5] Caroline Turner, “Indonesia: Art, Freedom, Human Rights and Engagement with the West,” in Art and Social Change (Canberra: Pandanus Books, 2005), 196.

[6] Carla Bianpoen, “Art and the Nation: The Cultural Politics of Sukarno,” in Beyond the Dutch: Indonesia, the Netherlands and the Visual Arts, from 1900 until now, ed. Meta Knol et al. (Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 2009), 96.

[7] Astri Wright, Soul, Spirit, and Mountain: Preoccupations of Contemporary Indonesian Painters (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 239-240.

[8] Founded in 1973, Creative Time states as its mission, “to commission, produce and present art that engages history, breaks new ground, challenges the status quo, and infiltrates the public realm.” Collaborating with artists and communities both in the United States and abroad, Creative Time works to create and promote art that stresses the organization’s three core values, “art matters, artists’ voices are important in shaping society, and public spaces are places for creative and free expression.” Since 2009, Creative Time has held an annual summit dedicated to exploring the intersection of art-making and social justice. In 2012, Taring Padi participated in Creative Time’s summit themed “Confronting Inequity,” thus becoming a part of a global network of artists deemed “socially engaged.”

[9] Nato Thompson, “Living as Form,” in Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art From 1991-2001, ed. Nato Thompson (New York: Creative Time Books, 2012), 19.

[10] Ibid, 24.

[11] Claire Bishop, “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents,” Artforum, (February 2006), 176-83.

[12] Alexandra Kuss, “Proximity and Distance – The Field of Tension Between Individual and Society,” in AWAS! Recent Art from Indonesia, ed. Alexanra Kuss, et al. (Yogyakarta: The Cemeti Art Foundation, 2000), 25.

[13] Ibid.

[14] ketjilbergerak, “Pembacaan Benih Bunyi,” accessed December 23, 2015, http://www.ketjilbergerak.org/pembacaan-benih-bunyi/.

[15] Grant Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 84.

[16] ArtJog curatorial statement

[17] Andy Abbott, “The Radical ethics of DIY in Self-Organized Art and Cultural Activity,” (Presentation for Ixia “Public Art and Self-Organization,” Leeds, United Kingdom, October 1 2012), retrieved from http://andyabbott.co.uk.

[18] Ibid.

Bibliography

Abbott, Andy. “The Radical Ethics of DIY in Self-Organized Art and Cultural Activity.” Presentation for Ixia ‘Public art and Self-Organization,’ Leeds, United Kingdom, October 1, 2012. Retrieved from http://andyabbott.co.uk.

Bianpoen, Carla. “Art and the Nation: The Cultural Politics of Sukarno.” In Beyond the Dutch: Indonesia, the Netherlands and the Visual Arts, from 1900 until now, edited by Meta Knol, Remco Raben, and Kitty Zijlmans. 94-103. Amsterdam: KIT Publishers, 2009.

Bishop, Claire. “The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents.” Artforum (February 2006): 176-83.

-------------. “Participation and Spectacle: Where Are We Now?” In Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art From 1991-2001, edited by Nato Thompson, 34-45, New York: Creative Time Books, 2012.

Kester, Grant. Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004.

Kuss, Alexandra. “Proximity and Distance – The Field of Tension Between Individual and Society. In AWAS!: Recent Art from Indonesia, edited by Alexandra Kuss, Damon Moon, Mella Jaarsma, Midori Hirota, and Nele Wasmuth, 25-40. Yogyakarta; The Cemeti Art Foundation, 2000.

McMichael, Heath. “The Lapindo Mudflow Disaster: Environmental, Infrastructure and Economic Impact.” Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 45 (2009): 73-83.

Sinaga, Dolorosa. “Not for the Sake of a Fine Arts Discourse.” In Seni Membongkar Tirani, edited by Annie Sloman, Jada Ella Trapp, and Reuben, 23-36. Yogyakarta: Lumbung Press, 2011.

Thompson, Nato. “Living as Form.” In Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art From 1991-2001, edited by Nato Thompson, 16-45. New York: Creative Time Books, 2012.

Turner, Caroline. “Indonesia: Art, Freedom, Human Rights and Engagement with the West.” In Art and Social Change, edited by Caroline Turner, 196-217. Canberra, Australia: Pandanus Books, 2005.

Wright, Astri. Soul, Spirit, and Mountain: Preoccupations of Contemporary Indonesian Painters. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.